|

| Swine Variant Human Cases : 2010-2018 - Credit CDC |

#14,101

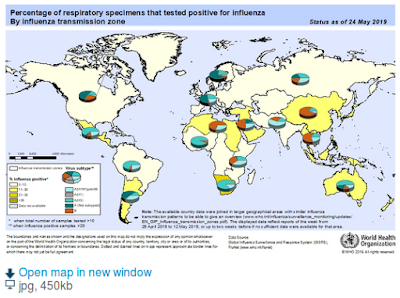

Although last winter's seasonal flu has all but disappeared in the U.S., each summer we keep an eye out for sporadic cases of swine-variant influenza, which are often associated with exposure to pigs at county fairs.

Over the past 15 years we've seen more than 460 confirmed human infections (see chart above), although this likely significantly under-represents the true number of cases.While most of these reported infections have been mild-to-moderate in severity, some people have required hospitalization, and deaths - while rare - have occurred (see J. Virology: Analysis Of A Swine Variant H1N1 Virus Associated With A Fatal Outcome).

The CDC describes Swine Variant viruses in their Key Facts FAQ.

What is a variant influenza virus?

When an influenza virus that normally circulates in swine (but not people) is detected in a person, it is called a “variant influenza virus.” For example, if a swine origin influenza A H3N2 virus is detected in a person, that virus will be called an “H3N2 variant” virus or “H3N2v” virus.The CDC's general risk assessment of these swine variant (H1N1v, H1N2v, H3N2v) viruses reads:

The CDC issued updated clinical Guidance for Human Infections with Swine Flu Viruses earlier this month, and in April we looked at how the CDC investigates cases (see The CDC & Novel Flu Investigations).CDC Assessment

Sporadic infections and even localized outbreaks among people with variant influenza viruses may occur. All influenza viruses have the capacity to change and it’s possible that variant viruses may change such that they infect people easily and spread easily from person-to-person. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) continues to monitor closely for variant influenza virus infections and will report cases of H3N2v and other variant influenza viruses weekly in FluView and on the case count tables on this website

Today's abbreviated (summer) FluView report contains details of 2019's first reported swine variant flu infection, which occurred in elderly resident in Michigan; one without an obvious exposure to swine.

Novel Influenza A Virus:

One human infection with a novel influenza A virus was reported by Michigan. This person was infected with an influenza A(H1N1) variant (A(H1N1)v) virus.

The patient is an adult > 65 years of age, was hospitalized, and completely recovered from their illness. While no exposure to swine has been reported, an investigation is ongoing into the source of the patient’s infection. This is the first A(H1N1)v virus infection detected in the United States in 2019.

Influenza viruses that circulate in swine are called swine influenza viruses when isolated from swine, but are called variant viruses when isolated from humans. Seasonal influenza viruses that circulate worldwide in the human population have important antigenic and genetic differences from influenza viruses that circulate in swine.

Early identification and investigation of human infections with novel influenza A viruses are critical so that the risk of infection can be more fully understood and appropriate public health measures can be taken. Additional information on influenza in swine, variant influenza infection in humans, and strategies to interact safely with swine can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/flu/swineflu/index.htm.

Additional information regarding human infections with novel influenza A viruses can be found at http://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/fluview/Novel_Influenza.html.

Last summer the CDC - in conjunction with the USDA and 4H - released an ambitious 60-page graphic novel on swine variant flu and how disease detectives investigate outbreaks.

While avian flu appears - at least temporarily - to be on the decline globally, swine variant influenza remains an ongoing threat, both in the United States and around the world.The Junior Disease Detectives: Operation Outbreak Graphic Novel

A few recent blogs on swine variant flu include:

Trop. Med & Inf. Dis.: Mammalian Pathogenicity and Transmissibility of H1 Swine Variant Influenza

BMC Vet.: Novel Reassortant H1N2 & H3N2 Swine Influenza A Viruses - Chile

J. Virology: Pathogenesis & Transmission of H3N2v Viruses Isolated in the United States, 2011-2016

JVI: Divergent Human Origin influenza Viruses Detected In Australian Swine Populations

The `Other' Novel Flu Threat We'll Be Watching This Summer

Emerg. Infect. & Microbes: Novel Triple-Reassortant influenza Viruses In Pigs, Guangxi, China