#14,288

The timing of the next pandemic is unknowable, but the yearly return of our seasonal influenza epidemic - which can kill tens of thousands in the United States alone - is pretty much assured.

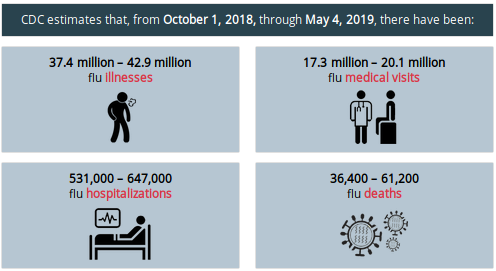

Last year's flu season was bad (see chart below), but not as bad as the year before, which may have killed 80,000 Americans.

Twice each year influenza experts gather to make recommendations for the makeup of the next flu vaccine; once in September for the following year's Southern Hemisphere vaccine, and again in February for the Northern Hemisphere's fall-winter vaccine.

These decisions must be made months in advance to give manufacturers time to produce, package, and distribute tens of millions of doses before the start of the next flu season.

But flu viruses continually mutate after these decisions have been reached, and do so throughout the next flu season, making a good match six to twelve months later far from assured.Last February - when the WHO normally decides on which strains to put in next fall's vaccine - they opted to delay their decision on the H3N2 component for 30 days (see WHO: (Partial) Recommended Composition Of 2019-2020 Northern Hemisphere Flu Vaccine).

At issue was the sudden rise of H3N2 clade 3C.3a reported in the United States (and other places), which had started last fall's season as a minor component of what appeared on track to being a relatively mild H1N1 season.By early 2019 we'd switched into a moderately severe H3N2 season with clade 3C.3a leading the pack (see CDC HAN #0418: Influenza Season Continues with an Increase in Influenza A(H3N2) Activity).

In late March the WHO decided to switch to the surging Clade 3C.3a H3N2 virus, betting that it would become the dominant H3 strain worldwide by next fall. The $64 question (still unanswered) is whether they bet on the right clade .

Roughly once a month during the Northern Hemisphere's flu season - and slightly less often over the summer - the ECDC publishes a review of recently isolated seasonal flu viruses collected across the EU in their Influenza Virus Characterization Report.

These (highly technical) reports help us track the evolutionary changes that are occurring in seasonal flu strains - at least in those regions submitting samples - and hopefully provide early warning of any major antigenic variances with this year's vaccine.

Their last update, issued in mid-July, continued to show a highly complex array of H3N2 viruses, all competing for dominance along with increased diversity in seasonal H1N1 viruses as well.The full (30 page PDF) report can be a daunting read, but the ECDC provides a useful summary:

Influenza virus characterisation, July 2019

3 Sep 2019

Publication series: Influenza Virus Characterisation

This is the ninth report for the 2018–19 influenza season. As of week 25/2019, 205 167 influenza detections across the WHO European Region had been reported; 98.9% type A viruses, with A(H1N1)pdm09 prevailing over A(H3N2), and 1.1% type B viruses, with 85 of 146 (58%) ascribed to a lineage being B/Yamagata.

Executive summary

Since the June 2019 characterisation report1, a further four shipments of influenza-positive specimens from EU/EEA countries were received at the London WHO CC, the Francis Crick Worldwide Influenza Centre (WIC). A total of 1 432 virus specimens, with collection dates after 31 August 2018, have been received.

A number of the 103 A(H1N1)pdm09 test viruses characterised antigenically since the last report showed better reactivity with antiserum raised against the A/Michigan/45/2015 2018–19 vaccine virus, compared with antiserum raised against the A/Brisbane/02/2018 2019–20 vaccine virus.

The 539 test viruses with collection dates from week 40/2018 genetically characterised at the WIC, including two H1N2 reassortants, have all fallen in subclade 6B.1A, defined by S74R, S164T and I295V HA1 substitutions; 493 of these viruses also have HA1 S183P substitution, often with additional substitutions in HA1 and/or HA2.These reports don't tell us what is going on outside of Europe, and those generated in late summer are based on a limited number of samples.

Since the last report, 21 A(H3N2) viruses successfully recovered had sufficient HA titre to allow antigenic characterisation by HI assay in the presence of oseltamivir; all were poorly recognised by antisera raised against the vaccine virus, egg-propagated A/Singapore/INFIMH-16-0019/2016. Of the 446 viruses with collection dates from week 40/2018 genetically characterised at the WIC, 363 were clade 3C.2a (41 3C.2a2, 14 3C.2a3, eight 3C.2a4 and 300 3C.2a1b); 83 were clade 3C.3a.

Four B/Victoria-lineage viruses have been characterised in this reporting period. All recent viruses have HA1 amino acid substitutions of I117V, N129D, and V146I compared to B/Brisbane/60/2008, a previous vaccine virus. Groups of viruses defined by deletions of two (Δ162-163, 1A(Δ2)) or three (Δ162-164, 1A(Δ3)) amino acids in HA1 have emerged, with the Δ162-164 group having subgroups of Asian and African origin. These virus groups are antigenically distinguishable by HI assay. Of 12 viruses characterised from EU/EEA countries this season, one has been Δ162-163 and 11 Δ162-164 (10 African and one Asian subgroup).

Two B/Yamagata-lineage viruses have been characterised in this reporting period, raising the total to 15 for the 2018–19 season. All have HA genes that encode HA1 amino acid substitutions of L172Q and M251V compared to, and remain antigenically similar to, the vaccine virus B/Phuket/3073/2013 (clade 3) recommended for use in quadrivalent vaccines for the next northern hemisphere influenza season.

Influenza virus characterisation, July 2019 - EN - [PDF-2.98 MB]

But one thing we can glean from this report is that H3N2 clade 3C.3a - while rising slightly compared to the June report - has yet to take off in Europe the way it did last winter in North America.

We are always looking in a rear view mirror when it comes to virus surveillance, and the situation 2 or 3 months ago (as reflected by these reports) may not hold true today, much less six months from now.As our global society becomes increasingly mobile in this 21st century, so do the viruses we carry. While this has obvious pandemic implications, it also makes seasonal flu more volatile, complex, and unpredictable.

As influenza viruses become more antigenically diverse, the job of picking which virus to include in next season's flu vaccine will only become more difficult.

|

| Credit NIAID |