|

| Credit CDC |

#14,285

Two weeks ago the CDC published a COCA (Clinician Outreach and Communication Activity) clinical action report on Unexplained Vaping-Associated Pulmonary Illness, describing recent reports of unexplained severe pulmonary disease which appeared to be linked to e-cigs or vaping.

Since then we've seen a second report (see CDC Update: Investigation Into Severe Pulmonary Disease Linked To Vaping)- where we learned that the number of cases has increased to more than 150 people from 16 states - followed by a CDC HAN Advisory which bumped the number up to 215 cases across 25 states.The exact causes - or mechanisms of injury - behind this growing cohort of cases aren't clear, nor do we know how much of a role user-adulterated `payloads' (ie. THC, Meth, Spice, etc.) may have played in these illnesses (see E-cigarettes-An unintended illicit drug delivery system).

While often touted as a `safer' alternative to tobacco products, and useful in smoking cessation therapy (see UK NHS Report), vaping has not been without its critics - including the CDC.

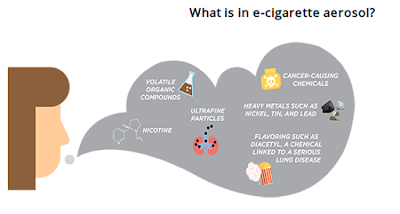

One of the big concerns that researchers are just starting to investigate, are the health impacts of the `delivery system', a combination of chemicals, flavorings, and ultra-fine particles which are drawn deeply into the lungs.

All of which brings us to a new study, published yesterday in the Journal of Clinical Investigation, which finds troubling evidence of lung injury following long-term inhalation of aerosols generated by Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS).

At least, in mice.We lack a fully predictive animal model for human medical research, but mice, guinea pigs, and ferrets are often employed because of their small size, low cost, and ease of use.

Although its often said that `Mice lie and monkeys exaggerate', these human proxies can often be an effective tool for biomedical research.A summary of this research was published yesterday as a press release from Baylor College of Medicine (see below), which describes not only lung injury, but increased susceptibility to influenza infection following long-term exposure to e-cig vapors in a murine model.

E-cigarettes disrupt lung function and raise risk of infection(Excerpts)

The experimental design consisted of four groups of mice. One group was exposed to e-cigarette vapors containing nicotine in the common vaping solvents propylene glycol and vegetable glycerin, in the proportions (60/40) found in e-cigarettes. A second group received vapors with only solvents but no nicotine. These groups were compared with mice exposed to tobacco smoke or to clean air.(Continue . . . )

The mice were exposed to tobacco smoke or e-cigarette vapors for four months following a regimen equivalent to that of a person starting smoking at about teenage years until their fifth decade of life. This smoking regimen markedly increases the risk of people developing emphysema, a condition in which the lungs' air sacs are damaged causing shortness of breath.

The researchers found that, as expected, mice that were chronically exposed to cigarette smoke had severely damaged lungs and excessive inflammation resembling those in human smokers with emphysema.

Unexpectedly, Kheradmand, Madison and their colleagues found that the treatment with e-cigarette vapors made of propylene glycol and vegetable glycerin solvents only (no nicotine), which are currently considered to be safe solvents, also damaged the lungs. In this case, the researchers did not observe inflammation and emphysema; instead, they found evidence of abnormal buildup of lipids (fats) in the lungs that disrupted both normal lung structure and function.

They also found that the accumulated fat was not from the solvent, rather it was from an abnormal turnover of the protective fluid layer in the lungs. In addition, they observed abnormal accumulation of lipids within resident macrophages. When the mice were exposed to influenza virus, the macrophages with abnormal lipid accumulation responded poorly to the infection.

The full (open access report) is available online (link below). When you return I'll have a brief postscript.

Electronic cigarettes disrupt lung lipid homeostasis and innate immunity independent of nicotine

Matthew C. Madison,1,2 Cameron T. Landers,1,2 Bon-Hee Gu,3 Cheng-Yen Chang,1,2 Hui-Ying Tung,3 Ran You,3 Monica J. Hong,1,3 Nima Baghaei,1 Li-Zhen Song,1 Paul Porter,3 Nagireddy Putluri,4 Ramiro Salas,5 Brian E. Gilbert,6 Ilya Levental,7 Matthew J. Campen,8 David B. Corry,1,2,3,9,10 and Farrah Kheradmand1,2,3,9,10ABSTRACT

First published September 4, 2019 - More info

Free access | 10.1172/JCI128531

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) or e-cigarettes have emerged as a popular recreational tool among adolescents and adults. Although the use of ENDS is often promoted as a safer alternative to conventional cigarettes, few comprehensive studies have assessed the long-term effects of vaporized nicotine and its associated solvents, propylene glycol (PG) and vegetable glycerin (VG).

Here, we show that compared with smoke exposure, mice receiving ENDS vapor for 4 months failed to develop pulmonary inflammation or emphysema.

However, ENDS exposure, independent of nicotine, altered lung lipid homeostasis in alveolar macrophages and epithelial cells. Comprehensive lipidomic and structural analyses of the lungs revealed aberrant phospholipids in alveolar macrophages and increased surfactant-associated phospholipids in the airway. In addition to ENDS-induced lipid deposition, chronic ENDS vapor exposure downregulated innate immunity against viral pathogens in resident macrophages.

Moreover, independent of nicotine, ENDS-exposed mice infected with influenza demonstrated enhanced lung inflammation and tissue damage.

Together, our findings reveal that chronic e-cigarette vapor aberrantly alters the physiology of lung epithelial cells and resident immune cells and promotes poor response to infectious challenge. Notably, alterations in lipid homeostasis and immune impairment are independent of nicotine, thereby warranting more extensive investigations of the vehicle solvents used in e-cigarettes.(Continue . . .)

It's far from clear whether the recent rash of vaping-related pulmonary illnesses are the same as described above. This study suggests that these lung injuries are likely to arise after years or decades of exposure.

That said, everyone is different, and some people develop emphysema or lung cancer from cigarettes early in life, while others live into their late 70s.

The jury is still out on the long-term safety of e-cigs, and perhaps they will prove a safer alternative to tobacco. But for now, there are growing safety signals which need to be pursued.