With a few notable exceptions, most of the public health impacts from avian flu have occurred outside of the United States. The most dangerous types of avian flu - H5N1, H5N6 and H7N9 - have all emerged from China, and while H5N1 has managed to spread widely across Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, North America has been protected by vast oceans.

A far less dangerous HPAI H5Nx did arrive via migratory birds from Asia in 2015, and that sparked a 6-month epizootic that caused the loss of 50 million birds, but no human infections were reported.

There have been at least 4 human infections with LPAI H7N2 (see J Infect Dis: Serological Evidence Of H7N2 Infection Among Animal Shelter Workers, NYC 2016). But unlike the more aggressive Asian H5 & H7 viruses, these cases were all either mild or moderate.

Today we are faced with another epizootic caused by a descendant of the HPAI H5N8 virus that ravaged U.S. poultry 7 years ago. But since then, this HPAI H5Nx has undergone several reassortments which appear to have increased the virus's affinity for mammalian species (see here, here, and here).

There have been a small number of reports of this Eurasian H5N1 virus (mildly) infecting humans, and 3 months ago we saw the ECDC/EFSA Raise The Zoonotic Risk Potential Of Avian H5Nx.

Simply put, although the risk of human infection from H5N1 in North America is very low, it isn't quite as low as it was during out last epizootic. The risk to the general public is likely minimal, but that risk increases for those in close contact with poultry, particularly those depopulating infected flocks.

Since HPAI H5N1 began turning up in the eastern half of the United States a month ago, the CDC has issued 3 statements advising that H5N1 Bird Flu Virus in U.S. Wild Birds and Poultry Poses a Low Risk to the Public.

Yesterday the CDC published a lengthy, and quite detailed summary of the avian flu situation in North America, the history of avian flu, the (currently) low risk of infection, and what people can do to reduce the risk of infection.

I've only reproduced some excerpts, so you'll want to follow the link to read it in its entirety. I'll have a bit more after the break.

Avian Influenza Current Situation SummaryCurrent situation in Wild Birds

Domestic SummaryThe latest case reports on avian influenza outbreaks in wild birds, commercial poultry, and backyard birds in the United States are available from the USDA website

- Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5) viruses have been detected in U.S. wild aquatic birds, commercial poultry and backyard or hobbyist flocks beginning in January 2022. These are the first detections of HPAI A(H5) viruses in the U.S. since 2016. Preliminary genetic sequencing and RT-PCR testing on some virus specimens shows these viruses are HPAI A(H5N1) viruses from clade 2.3.4.4b.*

- More information is available from the following spotlight articles:

*clades are described in the “Classification of avian influenza A viruses” section.

Global Summary* ”x” refers to avian influenza subtypes where the “N” neuraminidase protein number was not determined or reported.

- In the past decade there have been increases in the reported number and geographic spread of avian influenza A virus infections in birds, increases in the number of subtypes of avian influenza A viruses that have infected birds, and increases in the numbers of bird species that avian influenza A viruses have infected. The largest increase in HPAI A(H5N1) virus outbreaks in poultry and wild birds occurred during 2004-2006,

- During 2013-2021, different HPAI A(H5) and A(H7) virus subtypes as well as low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI) A(H3), A(H5), A(H6), A(H7), and A(H9) virus subtypes caused animal outbreaks globally.

- Since 2020, there has been a global increase in the number of HPAI A(H5) outbreaks reported in wild birds and poultry. There were more outbreaks reported in 2020-2021 than in the previous four years combined. Europe, Africa, and Southeast Asia reported multiple outbreaks of HPAI A(H5N8) starting in 2020 and HPAI A(H5N1) starting in 2021. During this same time, HPAI A(H5N6) virus outbreaks were reported in Asia, particularly China and Vietnam, and Southeast China (Chinese Taipei) reported outbreaks of HPAI A(H5N2) virus in poultry. In 2021, Europe reported multiple outbreaks of HPAI A(H5N5) virus and reported the first outbreaks of HPAI A(H5N4) virus in wild birds.

- In December 2021,HPAI A(H5N1) viruses were detected in birds in Newfoundland, Canada, marking the first identification of this virus in the Americas since June 2015.

- Ancestors of these HPAI A(H5N1) viruses first emerged in Asia in the late 1990s and began spreading widely in birds throughout Asia in 2003, and later spread to Africa, Europe, and the Middle East, causing sporadic human infections.

- Since 2003, multiple different clades of A(H5N1) viruses have circulated over the years, including a clade that was introduced by wild birds into the United States in 2014 and circulated until 2016.

- 54 countries reported an H5N1 outbreak in birds in 2021 and 2022.

- Specifically, from 2013-2021, the following HPAI and LPAI virus subtypes were reported in animals, mostly in wild aquatic waterfowl or domestic poultry:

- HPAI A(H5) virus subtypes detected included: H5N1, H5N2, H5N3, H5N4, H5N5, H5N6, H5N8, H5N9, and H5Nx*

- HPAI A(H7) virus subtypes detected included: H7N1, H7N2, H7N3, H7N7, H7N8 and H7N9

- LPAI A virus subtypes detected included H3N1, H5N1, H5N2, H5N3, H5N5, H5N6, H5N8, H5N8, H5Nx*, H6Nx*, H7N1, H7N2, H7N3, H7N4, H7N6, H7N7, H7N8, H7N9, and H7Nx*

(SNIP)

Current U.S. situation in Humans(Continue . . . )

Humans

- No human cases of HPAI A virus infection have ever been detected or reported in the United States. Only four human infections with LPAI A(H7N2) viruses resulting in mild-to-moderate illness have ever been identified in the United States.

- CDC considers the current risk to the U.S. public’s health from HPAI A(H5N1) virus outbreaks in wild birds or poultry in the United States to be low.

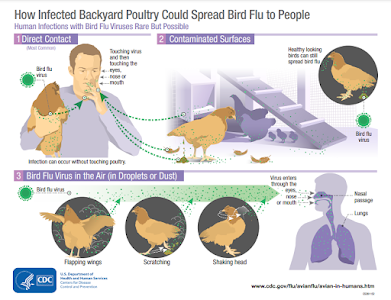

- As of February 2022, USDA APHIS announced multiple detections of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) A(H5N1) viruses in U.S. commercial poultry and backyard flocks. This follows detections of HPAI A(H5) viruses in wild birds in the United States in January 2022. The detection of these viruses in poultry does not change the risk to the general public’s health, which CDC considers to be low. However, outbreaks in domestic poultry, in addition to infections in wild birds, might result in increased exposures in some groups of people, poultry workers, for example.

- During past HPAI A(H5N1) virus outbreaks that have occurred in poultry globally, human infections were rare. Globally since 2003, 19 countries have reported rare, sporadic human infections with HPAI A(H5N1) viruses to the World Health Organization (WHO). Monthly case counts are available on the WHO website

- Rare, limited, non-sustained, human-to-human transmission of A(H5N1) viruses has occurred in other countries in the past. No known human-to-human transmission has occurred with the A(H5N1) virus lineage that is currently circulating in birds in the United States and globally.

- CDC and USDA have developed guidance for specific audiences, including the general public, hunterspdf icon, poultry producers, poultry outbreak responders, and health care providers.

- More information is available from a CDC spotlight article: Recent Bird Flu Infections in U.S. Wild Birds and Poultry Pose a Low Risk to the Public.

While the CDC and USDA are reassuring the public about the low risk of human infection, and the safety of the food chain, they are taking the threat seriously. Novel flu viruses, like HPAI, continue to evolve and their threat profile can increase quickly.

The CDC describes what they have done, and are currently doing, preparing for such an eventuality.

What is CDC Doing?

Based on available gene sequencing, CDC has determined:CDC is working with USDA and state public health partners to monitor for potential infections in exposed persons in the states where H5N1 bird flu virus detections in poultry and backyard flocks have occurred. If human infections with H5N1 bird flu virus are identified, CDC will assist with surveillance, contact tracing, and steps to reduce further spread, in the affected jurisdictions. CDC will also alert clinicians and other health professionals through clinician outreach networks. CDC has guidance documents including recommendations for personal protective equipment and information for people exposed to birds infected with avian influenza A viruses and guidance for testing and treatment of suspected cases to prevent severe illness and transmission to other people. CDC is currently reviewing and updating this guidance as needed.

- CDC has produced a candidate vaccine virus (CVV) that is nearly identical to the recently detected HPAI A(H5N1) viruses in birds that could be used to produce a vaccine for people, if needed.

- These viruses are susceptible to currently available antiviral medications used to treat influenza.

- These viruses can be detected using CDC’s diagnostic tools for seasonal influenza viruses which are used at more than 100 public health laboratories in all 50 U.S. states and internationally as well.

Risk Assessment Ongoing

CDC will continue its ongoing assessment of the risk posed by these viruses, including conducting laboratory experiments to further characterize the HPAI A(H5N1) virus. For example, continuing to look for genetic markers that might result in greater transmissibility to and between people or suggest reduced susceptibility to antivirals, as well as changes in the virus that might require the development of a new CVV. While sporadic bird-to-human infections would not raise the public health risk assessment, identification of multiple instances of HPAI A(H5N1) virus spread from birds to people, or of markers of mammalian adaptation in the virus, would raise CDC’s risk assessment. These changes could indicate the virus is adapting to spread more readily from birds to people. If human-to-human spread with this virus were to occur, that would raise the public health threat because it could mean the virus is adapting to spread better between people. Note that sustained human-to-human spread is needed for a pandemic to occur.

*Clades are explained on CDC’s Avian Influenza Current Situation Summary webpage in the section titled “Classification of Avian Influenza A viruses.”

**There have been four human infections with low pathogenic avian influenza A viruses identified in the United States since 2002. The designation of pathogenicity is related to severity of illness in poultry, not illness in people.

While HPAI H5N1 currently poses little threat to the general public, it wouldn't be terribly surprising - given the events in Russia, Nigeria, and most recently the UK - if similar cases are eventually detected here in the United States.