#16,934

In a normal year, seasonal flu kills roughly as many Americans as does gun violence, or car accidents. In a bad year - such as we saw in 2017-2018, influenza can kill as many as both of those combined.

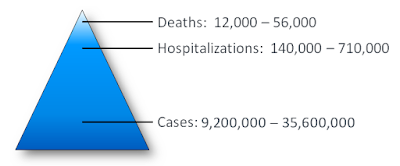

The CDC has an `expected range' of seasonal influenza hospitalizations and deaths (see chart above), but over the past dozen years, we've increasingly seen influenza and other respiratory infections linked to a significant increase in heart attacks, strokes, and even Alzheimer's and/or Dementia.

- Two years ago, in CDC: Another Study Linking Severe Influenza To Heart Damage, we looked at a study of 80,000 people hospitalized for influenza, which found that roughly 12% of adults incurred some degree of cardiac injury.

- In 2019, in PLoS One: Transient Depression of Myocardial Function After Influenza Virus Infection, we looked at a study that found transient myocardial function changes among a small group of influenza patients studied.

- In 2018's NEJM: Acute Myocardial Infarction After Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza Infection, we saw a study that found a `significant association ' between recent (lab confirmed) influenza infection and Myocardial Infarction.

- And in May 2017, in Int. Med. J.: Triggering Of Acute M.I. By Respiratory Infection we looked at research from the University of Sydney that found the risk of a heart attack is increased 17-fold in the week following a respiratory infection such as influenza or pneumonia.

The cardiovascular impact of influenza on a younger cohort remains largely unquantified.

While the absolute risk of having an AMI within 12 months of a severe influenza hospitalization was low (0.92%), the relative risk (compared to non-hospitalized controls) was nearly doubled.

Early risk of acute myocardial infarction following hospitalization for severe influenza infection in the middle-aged population of Hong KongHo Yu Cheng , Erik Fung ,Kai Chow Choi, Hui Jing Zou, Sek Ying Chair

Published: August 9, 2022

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0272661

Abstract

Introduction

Despite evidence suggesting an association between influenza infection and increased risk of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) in the older adult population (aged 65 years or above), little is known about its near-term risks in middle-aged adults (aged 45 to 64 years). This study aims to estimate the risks of and association between severe influenza infection requiring hospitalization and subsequent AMI within 12 months in middle-aged adults.

Method

This is a retrospective case-control analysis of territorywide registry data of people aged 45 to 64 years admitting from up to 43 public hospitals in Hong Kong during a 20-year period from January 1997 to December 2017. The exposure was defined as severe influenza infection documented as the principal diagnosis using International Classification of Diseases codes and non-exposure as hospitalization for orthopedic surgery. Logistic regression was used to analyze the risk of subsequent hospitalization for AMI within 12 months following the exposure.

Results

Among 30,657 middle-aged adults with an indexed hospitalization, 8,840 (28.8%) had an influenza-associated hospitalization. 81 (0.92%) were subsequently rehospitalized with AMI within 12 months after the indexed hospitalization. Compared with the control group, the risk of subsequent hospitalization for AMI was significantly increased (odds ratio [OR]: 2.54, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.64–3.92, p<0.001). The association remained significant even after adjusting for potential confounders (adjusted OR: 1.81, 95% CI: 1.11–2.95, p = 0.02). Patients with a history of hypertension, but not those with diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia or atrial fibrillation/flutter, were at increased risk (adjusted OR: 5.01, 95% CI: 2.93–8.56, p<0.001).

Conclusion

Subsequent hospitalization for AMI within 12 months following an indexed respiratory hospitalization for severe influenza increased nearly two-fold compared with the non-cardiopulmonary, non-exposure control. Recommendation of influenza vaccination extending to middle-aged adult population may be justified for the small but significant increased near-term risk of AMI.

This study focused primarily on one outcome - hospitalization for AMI within one year of infection - but there are other sequelae linked to influenza infection, including Neurocognitive Impacts, and a range of childhood and adolescent development disorders (see Of Pregnancy, Flu & Autism) following in utero exposure.

Despite some less-than-stellar influenza Vaccine Efficiency (VE) numbers - particularly among those in the highest risk groups (65+) - we've seen evidence that vaccination does reduce complications like heart attacks and strokes.

- In 2015, in UNSW: Flu Vaccine Provides Significant Protection Against Heart Attacks,we saw a study that found that if you are over 50 - getting the flu vaccine can cut your risk of a heart attack by up to 45%.

- In 2018, a study appearing the American Heart Association's journal Circulation, found a substantial reduction in deaths among heart failure patients who received a yearly flu shot (see AHA: Study Shows Flu Shots Reduce Deaths From Heart Failure).

- In January 2019, in Chest: Flu Vaccine Reduces Severe Outcomes Among Hospitalized Patients With COPD, researchers found a lower mortality rate, less critical illness, and a 38% reduction in influenza-related hospitalizations in vaccinated vs unvaccinated individuals.

- Also in 2019, in Flu Vaccine May Lower Stroke Risk in Elderly ICU Patients, we saw a study that found influenza vaccinated ICU survivors had a lower 1-year risk of stroke and a lower 1-year risk of death than unvaccinated survivors.

While the flu vaccine doesn't guarantee you'll avoid infection, most years it provides moderately good protection against circulating influenza viruses. And for those who are vaccinated - but still get the flu - they are less likely to have a severe bout.

This from the CDC:

Flu Vaccine Reduces Serious Flu Outcomes

Flu vaccination has been shown to reduce flu illnesses and more serious flu outcomes that can result in hospitalization or even death in older people. For example, a 2017 study showed that flu vaccination reduced deaths, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, ICU length of stay, and overall duration of hospitalization among hospitalized flu patients; with the greatest benefits being observed among people 65 years of age and older.

I view getting a yearly flu shot like always wearing a seat belt in an automobile. It doesn't guarantee a good outcome in a wreck, but it sure increases your odds of walking away.

And that, to me, is an extra bit of insurance worth having.