#17,286

Last month, in Neuron: Virus Exposure and Neurodegenerative Disease Risk Across National Biobanks, we looked at a study, published in Cell Neuron, which found a statistical linkage between viral illnesses and developing neurodegenerative diseases later in life.

While this study fell short of proving causality, it was the latest in a long list of studies we've seen linking influenza, and other respiratory infections, to significant post-infection sequelae, including (but not limited to) neurological manifestations.

A few (of many) blogs on the topic include:

JNeurosci: Another Study On The Neurocognitive Impact Of Influenza Infection

Nature Comms: Revisiting The Influenza-Parkinson's Link

Perhaps most famously, following the 1918 H1N1 pandemic, the world endured a decade-long epidemic of a mysterious and devastating neurological disorder called Encephalitis Lethargica (EL).

As many as 5 million people were afflicted with EL between 1917 and 1927 - and while roughly 1/3rd died during the acute phase of the illness - many of the survivors would go on to develop Parkinsonism features and other profound neurological sequelae, often years later.

Using diagnostic codes and data from the Medicare system, researcher have found the incidence of `Long Flu' to be similar to `Long COVID', but the severity - at least during the 2018 and 2019 flu seasons - to be far less.

There are some obvious limitations to this study, not the least of which the flu cases all occurred - and were followed up - before `Long COVID' was recognized. Clinicians would not have been actively looking for `post-viral' syndromes following influenza, and may not have recognized it or coded it that way.

Long COVID in Elderly Patients: An Epidemiologic Exploration Using a Medicare Cohort

Kin Wah Fung, Fitsum Baye, Seo Hyon Baik, Zhaonian Zheng, Clement Joseph McDonald

doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.02.09.23285742

Preview PDF

Abstract

Background: Incidence of long COVID in the elderly is difficult to estimate and can be under-reported. While long COVID is sometimes considered a novel disease, many viral or bacterial infections have been known to cause prolonged illnesses.We postulate that some influenza patients might develop residual symptoms that would satisfy the diagnostic criteria for long COVID, a condition we call “long Flu”.In this study, we estimate the incidence of long COVID and long Flu among Medicare patients using the World Health Organization (WHO) consensus definition. We compare the incidence, symptomatology, and healthcare utilization between long COVID and long Flu patients.Methods and Findings: This is a cohort study of Medicare (the U.S. federal health insurance program) beneficiaries over 65. ICD-10-CM codes were used to capture COVID-19, influenza and residual symptoms. Long COVID was identified by a) the designated long COVID-19 code B94.8 (code-based definition), or b) any of 11 symptoms identified in the WHO definition (symptom-based definition), from one to 3 months post infection.A symptom would be excluded if it occurred in the year prior to infection. Long Flu was identified in influenza patients from the combined 2018 and 2019 Flu seasons by the same symptom-based definition for long COVID.Long COVID and long Flu were compared in four outcome measures: a) hospitalization (any cause), b) hospitalization (for long COVID symptom), c) emergency department (ED) visit (for long COVID symptom), and d) number of outpatient encounters (for long COVID symptom), adjusted for age, sex, race, region, Medicare-Medicaid dual eligibility status, prior-year hospitalization, and chronic comorbidities.Among 2,071,532 COVID-19 patients diagnosed between April 2020 and June 2021, symptom-based definition identified long COVID in 16.6% (246,154/1,479,183) and 29.2% (61,631/210,765) of outpatients and inpatients respectively. The designated code gave much lower estimates (outpatients 0.49% (7,213/1,479,183), inpatients 2.6% (5,521/210,765)).Among 933,877 influenza patients, 17.0% (138,951/817,336) of outpatients and 24.6% (18,824/76,390) of inpatients fit the long Flu definition.Long COVID patients had higher incidence of dyspnea, fatigue, palpitations, loss of taste/smell and neurocognitive symptoms compared to long Flu. Long COVID outpatients were more likely to have any-cause hospitalization (31.9% (74,854/234,688) vs. 26.8% (33,140/123,736), odds ratio 1.06 (95% CI 1.05-1.08, p<0.001)), and more outpatient visits than long Flu outpatients (mean 2.9(SD 3.4) vs. 2.5(SD 2.7) visits, incidence rate ratio 1.09 (95% CI 1.08-1.10, p<0.001)). There were less ED visits in long COVID patients, probably because of reduction in ED usage during the pandemic. The main limitation of our study is that the diagnosis of long COVID in is not independently verified.Conclusions: Relying on specific long COVID diagnostic codes results in significant under-reporting. We observed that about 30% of hospitalized COVID-19 patients developed long COVID. In a similar proportion of patients, long COVID-like symptoms (long Flu) can be observed after influenza, but there are notable differences in symptomatology between long COVID and long Flu.The impact of long COVID on healthcare utilization is higher than long Flu.

Another consideration is, the cohort studied were all over the age of 65.

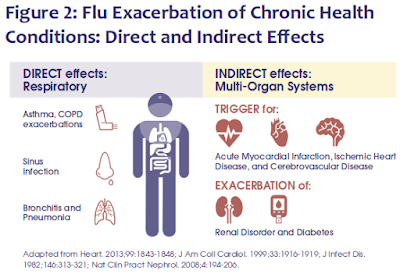

But even if `Long Flu' never reaches the level of `Long COVID', influenza is demonstrably bad enough to be worth avoiding if at all possible.

Which is why I roll up my sleeve for the flu shot every year. It isn't perfect, and isn't always a good match to the current flu strain, but I'll take any advantage I can get.