Since avian flu is primarily a gastrointestinal infection in birds, it can spread easily via droppings, and sometime via preening (see 2010's Birds Of A Feather . . . .) - which can contaminate water or soil.

Studies have shown that under the right conditions, H5N1 viruses can remain viable for days or even weeks in water, soil, or in biological materials (see EID Journal: Persistence Of H5N1 In Soil).

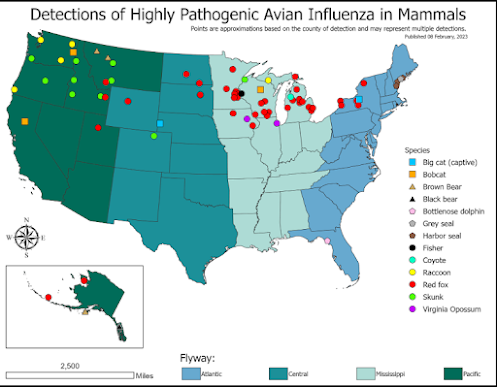

Carnivorous mammals - like foxes, raccoons, or bobcats - may also become infected from eating infected bird carcasses.

The USDA yesterday updated their list of confirmed mammalian infections from H5N1, adding 11 new cases since their previous update in early January. This brings the number of laboratory confirmed H5N1 positive mammals in the United States to 121.

2022-2023 Detections of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in Mammals

Last Modified: Feb 9, 2023

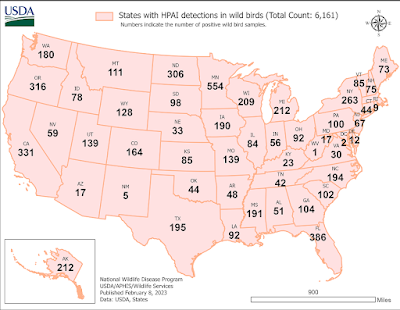

Learn more about 2022 detections of HPAI in Commercial and Backyard Flocks and HPAI in Wild Birds

There are many species that are potentially susceptible to HPAI. In addition to birds and poultry, H5N1 viruses have been detected in some mammals (see list below). Infection may cause illness, including severe disease and death in some cases.

Avian influenza is caused by influenza Type A virus (influenza A). Avian-origin influenza viruses are broadly categorized based on a combination of two groups of proteins on the surface of the influenza A virus: hemagglutinin or “H” proteins, of which there are 16 (H1-H16), and neuraminidase or “N” proteins, of which there are 9 (N1-N9). Many different combinations of “H” and “N” proteins are possible. Each combination is considered a different subtype, and related viruses within a subtype may be referred to as a lineage. Avian influenza viruses are classified as either “low pathogenic” or “highly pathogenic” based on their genetic features and the severity of the disease they cause in poultry. Most viruses are of low pathogenicity, meaning they causes no signs or only minor clinical signs of inflection in poultry.

Curiously, with the exception of a single infected Bottlenose Dolphin in Florida, all of the reports of mammalian infection have come from the northern half of the country.

While this may be due to more mammalian adapted strains circulating in those regions (see Preprint: Rapid Evolution of A(H5N1) Influenza Viruses After Intercontinental Spread to North America), it may also come down to the fact that some states may be looking harder than others.

Peridomestic mammals, like red foxes and skunks, are the most commonly reported terrestrial mammals infected. Being carnivorous scavengers - living in close proximity to humans - makes it more likely that they are discovered.

In any event, we are likely only seeing the tip of the iceberg.

So far, unlike with SARS-CoV-2 in deer, we haven't seen signs of H5N1 transmitting efficiently in mammalian wildlife (possible, but unproven exceptions are in marine mammals).

But our ability to detect that type of transmission in the field is limited.

The future evolution of these avian viruses is unknowable, but every time H5N1 spills over into a non-avian host, it gives the virus another opportunity to adapt and evolve.

Which is why we follow these events with great interest.