#17,268

With SARS-CoV-2 and HPAI H5N1 - along with other zoonotic viruses like MERS-COV, H5N6, H3N8, EA H1N1 `G4', and Nipah etc. - all conducting unsupervised field experiments in mammals around the world, it is becoming increasingly difficult to know where to focus our attention.

Traditional reservoir host species, like pigs and poultry, have recently been augmented by a number of other potential hosts - including marine mammals, companion animals (dogs and cats), rodents, and White-tailed deer.

The concern being that these zoonotic viruses could follow divergent evolutionary paths in non-human hosts - producing new and potentially more dangerous variants - which could eventually `spill back' into humans.

It is not an idle concern, as we've already seen this happen with COVID (see ECDC Detection of New SARS-CoV-2 Variants Related to Mink).

Over the summer of 2021, we saw the first evidence that White-Tailed Deer (WTD) were highly susceptible to the SARS-CoV-2 virus (see USDA/APHIS: White-Tailed Deer Exposed To SARS-CoV-2 Detected In 4 States), a finding that would be quickly confirmed across the country and in Canada.

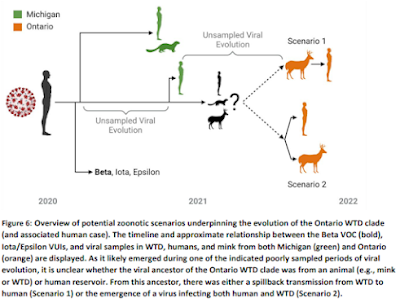

The plot thickened a year ago, when researchers from Ontario, Canada described Highly divergent SARS-CoV-2 variants in WTD and potential evidence of deer-to-human transmission (see graphic below).

While WTD aren't the only wildlife species with the ability to carry and spread SARS-CoV-2 (see Nature: Comparative Susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV Across Mammals and Preprint: SARS-CoV-2 Exposure in Norwegian rats (Rattus norvegicus) from New York City), they appear to be unusually well-suited to the job.

I've only reproduced the Abstract and some brief excepts from this lengthy report, so follow the link to read it in its entirety. There is also an accompanying press release from Cornell University.All of which brings us to a new study, published by researchers from Cornell University this week in PNAS, which shows that WTD can carry legacy versions of COVID long after they have disappeared from the human population, and that the virus continues to acquire unique mutations.

White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) may serve as a wildlife reservoir for nearly extinct SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern

Leonardo C. Caserta, Mathias Martins , Salman L. Butt , +5, and Diego G. Diel dgdiel@cornell.edu Authors Info & Affiliations

Edited by Xiang-Jin Meng

January 31, 2023

120 (6) e2215067120

https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2215067120

Significance

This comprehensive cross-sectional study demonstrates widespread infection of WTD with SARS-CoV-2 across the State of New York. We showed cocirculation of three major SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VOCs; Alpha, Delta, and Gamma) in this species, long after their last detection in humans.

Interestingly, the viral sequences recovered from WTD were highly divergent from SARS-CoV-2 sequences recovered from humans, suggesting rapid adaptation of the virus in WTD. The impact of these mutations on the transmissibility of the virus between WTD and from WTD to humans remains to be determined. Together, our findings indicate that WTD—the most abundant large mammal in North America—may serve as a reservoir for variant SARS-CoV-2 strains that no longer circulate in the human population.

Abstract

The spillover of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) from humans to white-tailed deer (WTD) and its ability to transmit from deer to deer raised concerns about the role of WTD in the epidemiology and ecology of the virus.Here, we present a comprehensive cross-sectional study assessing the prevalence, genetic diversity, and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in WTD in the State of New York (NY). A total of 5,462 retropharyngeal lymph node samples collected from free-ranging hunter-harvested WTD during the hunting seasons of 2020 (Season 1, September to December 2020, n = 2,700) and 2021 (Season 2, September to December 2021, n = 2,762) were tested by SARS-CoV-2 real-time RT–PCR (rRT-PCR). SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in 17 samples (0.6%) from Season 1 and in 583 samples (21.1%) from Season 2.Hotspots of infection were identified in multiple confined geographic areas of NY. Sequence analysis of SARS-CoV-2 genomes from 164 samples demonstrated the presence of multiple SARS-CoV-2 lineages and the cocirculation of three major variants of concern (VOCs) (Alpha, Gamma, and Delta) in WTD.

Our analysis suggests the occurrence of multiple spillover events (human to deer) of the Alpha and Delta lineages with subsequent deer-to-deer transmission and adaptation of the viruses. Detection of Alpha and Gamma variants in WTD long after their broad circulation in humans in NY suggests that WTD may serve as a wildlife reservoir for VOCs no longer circulating in humans. Thus, implementation of continuous surveillance programs to monitor SARS-CoV-2 dynamics in WTD is warranted, and measures to minimize virus transmission between humans and animals are urgently needed.

(SNIP)

The evidence generated in this study demonstrates widespread dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 in wild WTD populations across the State of New York and further indicates the cocirculation of three major VOCs in this new wildlife host. Notably, circulation of SARS-CoV-2 in WTD results in emergence of genetically diverse viruses in this species.

These observations highlight the need to establish continuous surveillance programs to monitor the circulation, distribution, and evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in WTD populations and to establish measures to minimize additional virus introductions in animals that may lead to spillback of deer-adapted SARS-CoV-2 variants to humans.

In addition to White-Tailed Deer, a recent study (see Preprint: Wildlife Exposure to SARS-CoV-2 Across a Human Use Gradient) found evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection across a wide variety of small peridomestic mammals (e.g. possums, skunks, squirrels, etc.) in Virginia.

With SARS-CoV-2 circulating and evolving in multiple mammalian hosts, the opportunities for future spillover events has almost certainly increased. The risks were summed up nicely last month in The Lancet Microbe: Ecology of SARS-CoV-2 in the Post-Pandemic Era, where the authors wrote:

The above discussion suggests that the ecology of SARS-CoV-2 could be more complex than for other zoonotic viruses (appendix). Infections in humans would facilitate frequent human–animal transmissions. Then, the virus could experience sustained evolution with adaptation to multiple species of animals that results in antigenicity changes before subsequent reverse transmission to humans. This would make disease control more difficult. Therefore, characterisation of SARS-CoV-2 ecology and greater levels of surveillance for infections in animals, especially pets, zoo animals, and urban and suburban wildlife, are imperative in the post-pandemic era.

While we may be headed towards the end of the declared COVID pandemic, the virus could still have some surprises in store.