#17,364

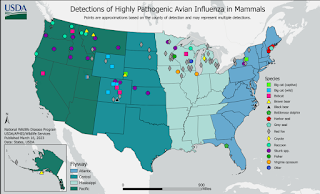

As the USDA map above (updated 3/16/23) shows, there have been nearly 150 documented spillovers of HPAI to mammalian wildlife in the United States, but with the exception of 1 Bottlenose Dolphin in Florida, all of the reports have come from the northern tier of states.

These are assumed to represent only a fraction of the mammals that have actually been affected by H5 avian flu, since mammals die in remote and difficult to access places, and are never discovered or tested.

Exactly why almost all of the reports to date have come from northern states isn't clear, although it may come down to differences in climate and terrain (swamps vs. forests vs. deserts), and the fact that some states may be looking harder than others.

In any event, yesterday Texas announced their first mammalian infection with H5N1; in a skunk in the panhandle. This press release from the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department.

I'll have a bit more after the break.

Credit Wikipedia

First Texas Case of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Detected in Mammals

March 21, 2023

Media Contact: TPWD News, Business Hours, 512-389-8030

AUSTIN- The National Veterinary Services Laboratories (NVSL) confirmed this week the presence of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) in a striped skunk recovered from Carson County.

This is the first confirmed case of HPAI in mammals for Texas.

Detected in all states across the U.S. except Hawaii, HPAI is a highly contagious virus that transmits easily among wild and domestic birds. The virus can spread directly between animals and indirectly through environmental contamination.

For mammals, current data shows transmission occurs primarily through the consumption of infected animal carcasses, though mammal-to-mammal transmission does not appear sustainable.

Other mammal species susceptible to HPAI include foxes, raccoons, bobcats, opossums, mountain lions and black bears. Symptoms can include ataxia (incoordination, stumbling), tremors, seizures, lack of fear of people, lethargy, coughing and sneezing, or sudden death.

Because of the ease of transmission, TPWD recommends that wildlife rehabilitators also remain cautious when intaking wild animals with clinical signs consistent with HPAI and consider quarantining animals to limit the potential for HPAI exposures to other animals within the facility.

Currently, the transmission risk of avian influenza from infected birds to people remains low, but the public should take basic protective measures (i.e., wearing gloves, face masks and handwashing) if contact with wild animals cannot be avoided.

Those who locate wild animals with signs consistent with HPAI should immediately contact their local TPWD wildlife biologist.

Peridomestic animals, like skunks, raccoons, and foxes are the most commonly reported mammals infected with HPAI, but that may be due - at least in part - to their close proximity to humans, which facilitates their discovery.

Of the 148 cases reported to the USDA, 1/5th (n=30) have been skunks.

With the spring northerly migration now underway, the virus may be moving into new areas in the weeks and months to come, which means that we may start seeing reports from regions that have previously seen little activity.We've seen evidence that cats and dogs are susceptible to HPAI H5 (and other novel flu viruses) over the years (see 2015's HPAI H5: Catch As Cats Can and 2010's Study: Dogs And H5N1), and the CDC offers advice to pet owners on how to protect their animals.