#17,399

Following the reporting debacle surrounding SARS in 2002-2003 (see SARS and Remembrance) - in 2005 the 194 member states of the World Health Organization (WHO) approved the biggest change to the IHR (International Health Regulations) in 35 years.

IHR 2005 required that all member nations develop mandated surveillance and testing systems and to report certain disease outbreaks and public health events to WHO in a timely manner (usually within 48 hours).

The agreement was supposed to go into force in 2007, but member states had until mid-2012 to meet core surveillance and response requirements. A great many nations - citing `hardships' - failed to meet that deadline, and a 2-year extension was granted.

Another extension was granted in 2014, (see WHO: IHR & Global Health Security), and yet another in 2016.

While supposedly `legally binding' for all WHO member nations, the IHR is notoriously lacking in `teeth’. Nations agree to abide, but there is little recourse if they don’t follow through - a topic we looked at in depth in 2015 in Adding Accountability To The IHR.

A job made more difficult following the 2008 recession, and made worse by a war in Europe, growing international political tensions, and 3+ years of a COVID pandemic.

The ongoing COVID pandemic appears to have become an excuse for some nations not to report on novel outbreaks. The WHO, in almost every surveillance bulletin, reiterates the obligation for all nations to abide by the IHR (see below).

All human infections caused by a new subtype of influenza virus are notifiable under the International Health Regulations (IHR, 2005). State Parties to the IHR (2005) are required to immediately notify WHO of any laboratory-confirmed case of a recent human infection caused by an influenza A virus with the potential to cause a pandemic. Evidence of illness is not required for this report.

Yet we often only hear about novel flu/virus cases weeks or months after-the-fact (see here, here, and here). And we have no way of knowing how many cases are never reported.

For many countries - which for political, economic, or societal reasons would rather not deal with such things - don't test, don't tell is an attractive option.

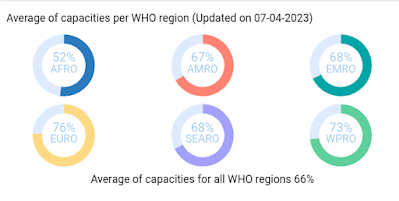

All of which brings us to a preprint posted on The Lancet SSRN´s First Look server, which suggests that the WHO's self-reported score of 66% may be overly optimistic.

The authors report `A minority of countries have public evidence of novel disease consideration, and significant geographical heterogeneity exists in where this is located.'

Using their own set of metrics - and based on data gleaned from public sources - they've come up with far lower percentage (73/195 countries (37·4%)) of member nations that were `found to have evidence of novel disease consideration'.

Due to its length, and potential copyright issues, I've just posted the link to the Abstract below. You can register (for free) to download the full document, which is very much worth reading.

I'll have a postscript when you return.

National Surveillance for Novel Diseases: A Systematic Analysis of 195 Countries

25 Pages Posted: 7 Apr 2023

As the WHO IHR infographic at the top of this blog reminds us, `Until all sectors are on board with the IHR, no country is ready'.

While ignorance may be bliss, the next pandemic threat may already be on the move. We simply can't know what threats lie ahead if we don't proactively look for, and immediately report, outbreaks.

Sadly - and for a multitude of reasons - that doesn't happen nearly as often as it needs to.