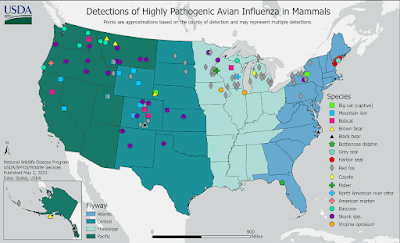

USDA Map of Mammalian Wildlife Infections With H5N1

#17,435

As we've discussed repeatedly over the past few months (see here, here, and here), there is currently an unprecedented amount of HPAI H5 virus circulating in wild North American birds, and it has repeatedly spilled over into US mammalian wildlife (see USDA map above).

Last month we also saw several reports of domestic cats in the U.S. (see here, and here) - and 1 dog in Canada - contracting the virus.

Cats have a long history of being susceptible to HPAI H5 (see 2015's HPAI H5: Catch As Cats Can) and while less commonly reported (see 2010 study Study: Dogs And H5N1), canines are at risk as well.

Since the majority of wildlife detections of H5N1 have come from peridomestic animals in urban or suburban settings, it makes sense to protect your cat and dog when they are outside. The CDC has some advice on keeping your pets, and yourself, safe from the virus.

This week Canadian Authorities reported to WOAH on WAHIS (Report # 4438) of their first detection of H5N1 in a feral cat (in Ontario), writing:

We report the first case of a H5N1 highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus in a feral cat, as well as additional skunks, red foxes and a raccoon. Additional unusual species are reported grouped by province. The geographical marker is on the capital. For detailed and current information on high pathogenicity avian influenza cases in wildlife, please consult : http://www.cwhc-rcsf.ca/avian_influenza.php

As in the United States, there are large swaths of Canada where surveillance is limited, and very few cases have been reported. Among the 101 mammals reported by Canada, 40 have been striped skunks and 35 red foxes.

This week the USDA updated their list of mammals infected with H5 avian influenza, bringing the total to 176 (not including the domestic cats mentioned above). Red Foxes and skunks make up more than 60% of this total (red foxes 42%, skunks 20%).

Mammals often die in remote and difficult to access places where their carcasses are quickly scavenged by other animals, meaning they are never discovered or tested.

While the increased number of spillovers of HPAI to mammalian hosts is concerning, the `saving grace' has been that we've seen very little evidence of mammal-to-mammal transmission of the virus (possible exceptions being farmed mink and marine mammals).

This is considered important - particularly with zoonotic diseases like avian flu - because long chains of infection can lead to adaptive mutations, which can make the virus even better suited for a specific host.

But much of what goes on in the wild is hidden from view. Not seeing something isn't quite the same as saying it isn't happening. Scavengers - like feral cats, foxes, vultures, and raccoons - may be creating unseen chains of infection in the wild.

It is still unknown whether H5N1 has the `right stuff' to spark a pandemic in humans. We've been on the `brink' several times in the past, only to see the threat recede.

But past performance is no guarantee of future results.

So we monitor these spillovers into mammals with considerable interest.