A little over 2 months ago, in El Niño & The CSU Initial Atlantic Hurricane Season Forecast, we looked at prospect for an El Niño setting up in the Pacific the summer, and early predictions for fewer Atlantic basin tropical storms for the 2023 season.

Climate.gov describes this sea temperature oscillation as:

El Niño and La Niña are the warm and cool phases of a recurring climate pattern across the tropical Pacific—the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, or “ENSO” for short. The pattern shifts back and forth irregularly every two to seven years, bringing predictable shifts in ocean surface temperature and disrupting the wind and rainfall patterns across the tropics. These changes have a cascade of global side effects.

At that time, the odds of seeing an El Niño by late summer were estimated at about 60%, but two days ago NOAA announced that as of early June, El Niño was officially in place, and is expected to persist at least into the winter.

The impacts of El Niño are global, and can be dramatic. For California and the west coast of the United States, it can often mean a wetter, and stormy winter. For parts of Asia and Australia, it can mean increased risks of drought.

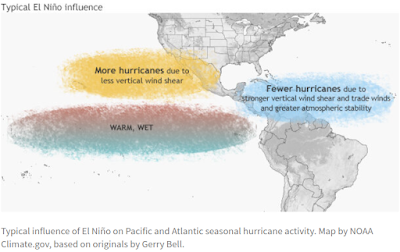

While nothing is set in stone, Its impact on Hurricane season is described by NOAA as:

Simply put, El Niño favors stronger hurricane activity in the central and eastern Pacific basins, and suppresses it in the Atlantic basin (Figure 1). Conversely, La Niña suppresses hurricane activity in the central and eastern Pacific basins, and enhances it in the Atlantic basin (Figure 2).

Despite this dampening influence on Atlantic Hurricane activity, the waters of the Atlantic basin have been unusually hot the past few months, and that could offset some of the impacts of El Niño. Which is one of the reasons why three weeks ago NOAA Predicted a Near-Normal 2023 Atlantic Hurricane Season.

It is worth noting that even if the number of storms are suppressed, we've seen significant hurricanes during El Niño years. One the most destructive hurricanes on record (Andrew) hit South Florida in 1992, during what was otherwise a lackluster El Niño hurricane season. 1969 was also an active El Niño year, which saw CAT 5 hurricane Camille slam into the upper gulf coast.

Since it only takes one bad hurricane to ruin your entire summer I will be preparing the same as I do every year (see National Hurricane Preparedness Week 2023).

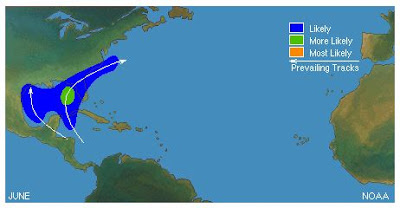

Regardless of the influence of ENSO, June is generally a pretty quiet month for Atlantic hurricanes, and what does form usually does so close to land in the Caribbean or Gulf of Mexico. More powerful long-track storms usually form in the Eastern Atlantic in August and September.

June hurricanes have a reputation for being milder, short-lived, and less dangerous. But there have been some notable exceptions.

- Hurricane Audrey in 1957 was the only June storm in modern history known to reach CAT 4 strength, and it claimed 550 lives after it made landfall in eastern Texas and western Louisiana

- Category 1 Hurricane Agnes (1972), caused relatively little damage when it made landfall in Florida, but caused extensive inland flooding several days later in the Mid-Atlantic states, claiming 113 lives in New York and Pennsylvania.

- Slow moving tropical storm Allison - in June of 2001 – proved more than deadly producing 55 fatalities and causing in excess of $9 billion in damage to Southeast Texas - primarily due to its torrential rains.

- In 2010 Hurricane Alex – a strong CAT 2 hurricane – slammed into Mexican state of Tamaulipas after intensifying to hurricane strength on June 29th.The lesson being that even tropical storms and weak hurricanes are capable of doing severe damage and taking lives.

As we've discussed so often in the past you don't have to live right on the coast to be affected by a land falling hurricane. High winds, inland flooding, and tornadoes can occur hundreds of miles inland.

While there are a number of excellent internet resources for hurricane information (I personally follow Mark Sudduth's Hurricane Track, and Mike's Weather page), there are also a lot of slickly produced clickbait sites that post highly questionable or irresponsible content.

As always, Caveat Lector.

Your primary source of forecast information should always be the National Hurricane Center in Miami, Florida. These are the real experts, and the only ones you should rely on to track and forecast the storm.

If you are on Twitter, you should also follow @FEMA, @NHC_Atlantic, @NHC_Pacific and @ReadyGov, and of course take direction from your local Emergency Management Office.

For more Hurricane resources from NOAA, you'll want to follow these links.

HURRICANE SAFETY

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES