#17,563

Neurological manifestations ranged from relatively mild (headaches, dizziness, anosmia, mild confusion, etc.) to more profound (seizures, stupor, loss of consciousness, etc.) to potentially fatal (ischemic stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, muscle injury (rhabdomyolysis), etc.).

Over that first spring and summer additional reports emerged describing neurological manifestations in COVID patients, including:

- In April 2020, the NEJM published a review of 5 early case reports of Large-Vessel Stroke as a Presenting Feature of Covid-19 in the Young

- In The Lancet: Yet Another Study On Neurological Manifestations In Severe COVID-19 Patients, we looked at report that described 153 COVID-19 cases treated in UK hospitals which found a wide range of neurological and psychiatric complications affecting both younger and elderly patients.

- In July I blogged on a 63-page report from the Journal Brain called The emerging spectrum of COVID-19 neurology.

These early reports led to a number of cautionary articles in the journals, including:

- In mid-June, in The Lancet: COVID-19: Can We Learn From Encephalitis Lethargica?, we revisited the mysterious neurological epidemic that began around the time of the 1918 pandemic, and continued on for a decade.

- In August, in J. Neurology: COVID-19 As A Potential Risk Factor For Chronic Neurological. Disorders, we revisited the growing concerns over the long-term neurological impacts of COVID-19 infection.

- And in September 2020 (see Parkinsonism as a Third Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic?) we looked at a Review Article that examined the parallels between COVID-19 and epidemics of the past, and the potential for seeing a new wave of neurological disorders.

Since those early days, the evidence of neurological involvement from COVID infection has only grown stronger (see Nature: Long-term Neurologic Outcomes of COVID-19 and Nature: Long-term Effects of SARS-CoV-2 Infection on Human Brain and Memory).

Repeated reinfections are believed to exacerbate those adverse outcomes (see Nature: Acute and Postacute Sequelae Associated with SARS-CoV-2 Reinfection).

But the damage that COVID infection (and reinfection) continues to do can't be wished away by popular demand. Society, and the healthcare delivery system, will have to find ways to cope with its impact.

Today we've got a lengthy and detailed review of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cerebrovascular disease. Due to its length, I've only posted some excerpts, so follow the link to read it in its entirety.

I'll have a bit more after the break.

Cerebrovascular Disease in COVID-19

James E. Siegler 1,2,*, Savanna Dasgupta 1, Mohamad Abdalkader 3, Mary Penckofer 2, Shadi Yaghi 4 and Thanh N. Nguyen 3

Viruses 2023, 15(7), 1598; https://doi.org/10.3390/v15071598 (registering DOI)

Received: 16 June 2023 / Revised: 18 July 2023 / Accepted: 20 July 2023 / Published: 21 July 2023

Abstract

Not in the history of transmissible illnesses has there been an infection as strongly associated with acute cerebrovascular disease as the novel human coronavirus SARS-CoV-2. While the risk of stroke has known associations with other viral infections, such as influenza and human immunodeficiency virus, the risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke related to SARS-CoV-2 is unprecedented.

Furthermore, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has so profoundly impacted psychosocial behaviors and modern medical care that we have witnessed shifts in epidemiology and have adapted our treatment practices to reduce transmission, address delayed diagnoses, and mitigate gaps in healthcare.

In this narrative review, we summarize the history and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cerebrovascular disease, and lessons learned regarding the management of patients as we endure this period of human history.

(SNIP)

Direct and Indirect Relationships between COVID-19 and Cerebrovascular Disease

Never before has a virus been so strongly linked to a heightened risk of acute cerebrovascular disease. The risk of stroke has a known association with many transmissible infections, including those responsible for bronchitis, influenza, H. pylori, cytomegalovirus, and many others [12]. The inflammatory response to these infections is thought to trigger inflammation and endothelial dysfunction, culminating in vascular events such as ischemic stroke and myocardial infarction [13].Among the more common infections, the ongoing human immunodeficiency virus pandemic has been associated with a 60% relative increase in the risk of stroke and grows over time, although the overall incidence of stroke with this virus is low (1.28% over a 5-year period) [14]. Influenza, by contrast, is associated with a small but significant early risk (maximal within the first 15 days of symptoms), which disappears within 2 months [15]. The temporal association between stroke and SARS-CoV-2 is similar to the relationship between influenza and stroke in that there is a high early risk that likely decreases with time. However, the risk of stroke is several-fold greater with SARS-CoV-2 than with influenza [16].

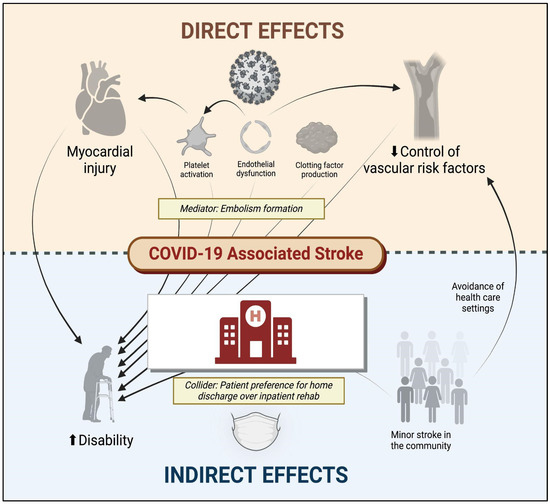

Multiple mechanisms account for the unique association between SARS-CoV-2 and stroke (Figure 1). Some of these include increased thromboxane synthesis with associated platelet activation, rapid turnover of fibrinogen, endothelial dysfunction, and inflammation, as well as thrombus formation following cardiac dysfunction. Following infection, the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein activates platelets via platelet angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors, resulting in heightened expression of platelet integrin αIIbβ3 and P-selectin, which facilitates degranulation and platelet aggregation [17]. The vascular endothelium is also highly susceptible to viremia given its surface expression of ACE2 receptors, which permits viral entry into endothelial cells, leading to activation/disruption [18].In parallel with these pathways responsible for platelet activation and endothelial dysfunction, SARS-CoV-2 indirectly activates factor X via inflammatory mediators (e.g., IL-6 and IL-8), which increase tissue factor expression, thereby activating the extrinsic pathway [19]. Furthermore, 30–40% of patients with severe COVID-19 may develop myocardial ischemia, elevated troponins, and new heart failure with resultant ventricular dysfunction [20], potentially contributing to intracardiac thrombus formation and stroke or systemic embolism. There is also a suggestion of elevated anticardiolipin IgA, and beta-2-glycoprotein IgG and IgM levels in patients with COVID-19 in several reports [21,22,23], but these serum findings are also found in patients with other acute infections (unrelated to SARS-CoV-2).

Figure 1. Direct and indirect effects of COVID-19 on cerebrovascular disease. COVID-19 denotes coronavirus disease 2019. Figure generated using biorender.com.

Among the multiple thrombotic complications of COVID-19, ischemic stroke has been reported in approximately 1.0–1.5% of all hospitalized individuals who test positive for SARS-CoV-2 [6], with twice as many patients having no identifiable mechanism of cerebral infarction (>40%) as conventional stroke cohorts [24]. Furthermore, in one early multinational cohort of 156 patients with stroke and COVID-19, nearly half (49.5%) presented with a proximal or medium vessel occlusion on initial neuroimaging, a nearly doubled risk compared with historic stroke cohorts with traditional mechanisms [25]. Even more concerning, when considering the “cryptogenic” mechanism of stroke as being directly related to SARS-CoV-2, the risk of early mortality may be five-fold greater than that of patients with other suspected mechanisms of infarction, according to one case–control study (adjusted OR 5.16, 95% CI 1.41–18.87) [26].

In addition to these cerebrovascular complications of SARS-CoV-2 infection, although it has not been explicitly studied, the psychosocial consequences of COVID-19 may also impact the risk of cerebrovascular disease. The early avoidance of healthcare institutions in the setting of milder cerebrovascular events [27], delays (or cancellations) in primary care appointments [28], and other factors may have inadvertently affected the control of vascular risk factors and heightened long-term stroke risk. Moreover, the long-term consequences of COVID-19 include an increased risk of diabetes, congestive heart failure, coronary disease, and hypertension [29], which can directly increase the risk of ischemic stroke.

Other long-term consequences of COVID-19 such as fatigue, brain fog, and depression [30], which can indirectly augment stroke risk by influencing activity, diet, and lifestyle preferences. The direct and indirect factors associated with stroke and disability following COVID-19 are illustrated in Figure 1.

Although we are thankfully experiencing a summer lull in COVID, there are no guarantees it won't return with a vengeance in the fall or next winter. New variants, and waning community immunity, will likely result in a wave of reinfections.

Given what we know about the increased health risks from multiple infections, and the elevated risk of severe neurological and cardiac damage, COVID remains a disease you really want to avoid if at all possible.

There will be an updated booster shot in the fall, and face masks have been proven to reduce the risk of infection. But these mitigation efforts are only effective if people embrace them.