#17,727

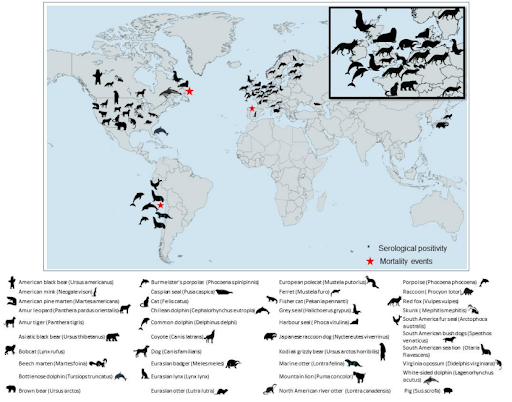

While the future course and impact of HPAI H5 is impossible to predict, it is quite evident that the avian flu threat we face today is quite different from what we've dealt with in the past. HPAI H5N1's rapidly expanding host range (see ECDC/EFSA chart above) means that it is no longer primarily a disease of poultry, controllable by culling or vaccines.

Following North America's first HPAI H5 epizootic in the first half of 2015, which affected poultry in 15 states and several Canadian provinces (see map below), the virus literally vanished from wild birds in a matter of months (see PNAS: The Enigma Of Disappearing HPAI H5 In North American Migratory Waterfowl).

But the a year later (2016), following a reassortment event in Russia/China, a modified H5N8 virus arrived in Europe with an enhanced ability to spread by, and persist in, migratory birds. Since then, H5 viruses have enjoyed greater range, which affords even more opportunities to reassort with other viruses.

How viruses shuffle their genes (reassort)

In a 2017 blog called Avian Flu's Global Field Experiment, we looked at some of these evolutionary changes, including H5's expanding host range (primarily in birds). I wrote:

"The $64 question - as yet unanswered - is whether the recent changes to Europe's H5N8 virus have moved it towards a strain that can sustain itself in the migratory waterfowl population."

Since then we've seen more introductions from Europe and Asia, and the H5N1 virus has conquered most of North and South America. Antarctica appears next in line, with Australia remaining the last HPAI H5-free zone.

Add in H5's increasing ability to spill over into mammalian species (see Denmark: Risk Assessment Of H5N1 Spillover Into Mammals) - many exhibiting neurological manifestations (see Cell: The Neuropathogenesis of HPAI H5Nx Viruses in Mammalian Species Including Humans) - and you can understand why pandemic concerns are rising.

Yesterday the journal Nature published an excellent review article describing H5's evolution (see below). While the full report is behind a paywall, Nature News has published a summary. Due to their lengths, and copyright issues, I've just posted the links below.

The episodic resurgence of highly pathogenic avian influenza H5 virus

Nature (2023)Cite this article

NEWS

18 October 2023

How the current bird flu strain evolved to be so deadly

Genetic changes to avian influenza viruses have led to spread among many wild species, creating an uncontrollable global outbreak.

Miryam Naddaf

While today's H5N1 virus is admittedly not spilling over into humans at the same rate we were seeing prior to 2016 (see chart below), it is far better suited for long distance carriage by migratory and wild birds, has spread globally at a phenomenal rate, and continues to experiment with new mammalian hosts.

While the future course and impact of HPAI H5 is unknowable - and it is possible that the threat could recede as it has in the past - we are in uncharted territory, and we need to be prepared for a variety of outcomes.