#17,667

While seasonal flu can occasionally cause neurological symptoms (see 2018's Neuroinfluenza: A Review Of Recently Published Studies) it is relatively rare, and usually only results in mild, and transient symptoms.

Still, concerns have been raised over the long-term neurological impacts of severe (or repeated) influenza infections (see Nature Comms: Revisiting The Influenza-Parkinson's Link).The exact mechanisms behind these neurological manifestations are largely unknown, as seasonal flu viruses are generally regarded as being non-neurotropic.

A 2009 PNAS study (Highly pathogenic H5N1 influenza virus can enter the central nervous system and induce neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration) found that the H5N1 virus was highly neurotropic in lab mice, and in the words of the authors `could initiate CNS disorders of protein aggregation including Parkinson's and Alzheimer's diseases’.

In a 2015 Scientific Reports study on the genetics of the H5N1 clade 2.3.2.1c virus - Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus Struck Migratory Birds in China in 2015 – the authors descroibed its neurotropic effects, and warned that it could pose a ` . . . significant threat to humans if these viruses develop the ability to bind human-type receptors more effectively.'

After a 5 year hiatus, when other avian strains (H7N9, H5N8, etc.) dominated, in 2021 H5N1 returned with a vengeance, and since then we've seen a steady stream of reports of spillover into mammalian hosts, with many exhibiting severe (often fatal) neurological manifestations.

A few of many recent blogs include:

While clinical details of many H5Nx human infections go unpublished, almost exactly a year ago, in Clinical Features of the First Critical Case of Acute Encephalitis Caused by Avian Influenza A (H5N6) Virus, we learned of the severe neurological impact of the virus on a 6 year-old girl in China.

While certainly not the typical presentation of H5Nx infection in humans, the authors wrote:

In view of the fact that the clinical manifestations of this novel H5N6 reassortant are acute encephalitis, rather than previous respiratory symptoms, once these reassortants obtained the ability of human-to-human transmission through reassortment or mutations, it will bring great health threat for human.

All of which brings us to a review article, published last week in Trends in Neurosciences, that looks at the history, and recent trends, of neuropathogenesis of avian H5 in mammals.

This is a detailed, and lengthy review, and many will want to follow the link to read it in its entirety. A few excepts follow, after which I'll have a brief postscript.

Lisa Bauer 3 Feline F.W. Benavides 3 Edwin J.B. Veldhuis Kroeze Emmie de Wit Debby van Riel

Open Access Published: September 06, 2023 DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2023.08.002

Highlights

- Highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5Nx viruses can cause neurological complications in many mammalian species, including humans.

- Neurological disease induced by HPAI H5Nx viruses in mammals can manifest without clinical respiratory disease.

- HPAI H5Nx viruses are more neuropathogenic than other influenza A viruses in mammals.

- Severe neurological disease in mammals is related to the neuroinvasive and neurotropic potential of HPAI H5Nx viruses.

- Cranial nerves, especially the olfactory nerve, are important routes of neuroinvasion for HPAI H5Nx viruses.

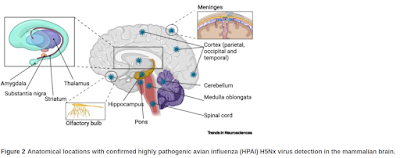

- HPAI H5Nx viruses have a broad neurotropic potential and can efficiently infect and replicate in various CNS cell types.

- Vaccination and/or antiviral therapy might in part prevent neuroinvasion and neurological disease following HPAI H5Nx virus infection, although comprehensive studies in this area are lacking.

Abstract

Circulation of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) H5Nx viruses of the A/Goose/Guangdong/1/96 lineage in birds regularly causes infections of mammals, including humans. In many mammalian species, infections are associated with severe neurological disease, a unique feature of HPAI H5Nx viruses compared with other influenza A viruses.

Here, we provide an overview of the neuropathogenesis of HPAI H5Nx virus infection in mammals, centered on three aspects: neuroinvasion, neurotropism, and neurovirulence. We focus on in vitro studies, as well as studies on naturally or experimentally infected mammals. Additionally, we discuss the contribution of viral factors to the neuropathogenesis of HPAI H5Nx virus infections and the efficacy of intervention strategies to prevent neuroinvasion or the development of neurological disease.

(SNIP)

Neuropathogenesis of H5Nx viruses

A unique feature of HPAI H5Nx viruses is their ability to cause severe neurological disease in birds and mammals, a feature rarely observed for other influenza A viruses. Neurological complications are the most common clinical manifestations in naturally infected mammals, although one could argue that this may be due to the ease of observation of neurological versus respiratory symptoms. However, studies from experimentally infected mammals show that neurological complications occur more frequently after HPAI H5Nx virus infection than infection with low pathogenic avian influenza (LPAI), seasonal or pandemic influenza A viruses [16.,17.]. To date, neurological disease has been reported in many mammalian species, including humans, foxes, cats, tigers, stone martens, harbor porpoises, common seals, gray seals, ferrets, mice, pikas, and minks [11.]. In this review, we discuss current knowledge on the neuropathogenesis of HPAI H5Nx virus infections in mammals, focusing on three aspects: neuroinvasion, neurotropism, and neurovirulence. Although we focus on mammals, we summarize the neuropathogenic potential of these HPAI H5Nx viruses in birds in Box 1. Last, we outline the role of viral factors and how these contribute to neuropathogenicity of HPAI H5Nx viruses in mammals and possible intervention strategies and treatment options in humans.

(SNIP)

A comprehensive understanding of the phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of HPAI H5Nx viruses that contribute to the development of neurological disease is urgently needed. Several virus-intrinsic features have been associated with the neuropathogenesis of influenza A viruses, such as the recognition of α(2,3)-linked SIAs, the presence of a MBCS, and an increased polymerase activity.

However, none of these are solely responsible for the neuroinvasive, neurotropic, and neurovirulent potential of HPAI H5Nx viruses. In vivo and in vitro models are indispensable to identify viral factors that contribute to or are essential for the neuroinvasion, neurotropism, and neurovirulence. Scalable in vitro hiPSC-derived neural models are particularly useful tools to investigate virus–neural cell interactions in detail, as well as to characterize the neurotropic and neurovirulent potential of newly emerging H5Nx and other viruses in a human-related model system.

To conclude, HPAI H5Nx viruses are unique among influenza A viruses in their neuroinvasive potential, their efficient replication within the CNS, and their potential to cause severe CNS disease in mammals. With the continuous circulation of HPAI H5Nx viruses worldwide, mammals, including humans, are at risk of being infected. Although sustained transmission among mammals infected with HPAI H5Nx viruses is rare, it is critical to monitor the spread of this virus.

A collaborative One Health approach is required to gain insights into the frequency and the full spectrum of neurological disease in humans and animals and to identify viral factors that contribute to the neuropathogenicity of HPAI H5Nx viruses. Finally, awareness should be raised among animal and human health care workers regarding neurological complications associated with HPAI H5Nx viruses and the potential of these neurological manifestations to occur in the absence of respiratory disease.

In my first week of blogging AFD more than 17 years ago, in `WHO’s on First' we looked at the World Health Organization's sobering early description of the clinical features of H5N1 infection in humans.

Initial symptoms include a high fever, usually with a temperature higher than 38oC, and influenza-like symptoms. Diarrhoea, vomiting, abdominal pain, chest pain, and bleeding from the nose and gums have also been reported as early symptoms in some patients.

Watery diarrhoea without blood appears to be more common in H5N1 avian influenza than in normal seasonal influenza. The spectrum of clinical symptoms may, however, be broader, and not all confirmed patients have presented with respiratory symptoms.

In two patients from southern Viet Nam, the clinical diagnosis was acute encephalitis; neither patient had respiratory symptoms at presentation. In another case, from Thailand, the patient presented with fever and diarrhoea, but no respiratory symptoms. All three patients had a recent history of direct exposure to infected poultry.

(SNIP)

In patients infected with the H5N1 virus, clinical deterioration is rapid. In Thailand, the time between onset of illness to the development of acute respiratory distress was around 6 days, with a range of 4 to 13 days. In severe cases in Turkey, clinicians have observed respiratory failure 3 to 5 days after symptom onset.

Another common feature is multiorgan dysfunction, notably involving the kidney and heart. Common laboratory abnormalities include lymphopenia, leukopenia, elevated aminotransferases, and mild-to-moderate thrombocytopenia with some instances of disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Even back then, there were clear signs that H5N1 in humans was far different than regular influenza.

Admittedly, the H5N1 viruses of today are far different from the clades that were circulating nearly 20 years ago, and the clinical picture of today's virus may not match what is described above.

But H5Nx's increasing neuroinvasive qualities are highly concerning, and under a worse case scenario, could radically change our perception of what a `flu pandemic' would look like.