#17,737

With more and more countries moving to - or at least considering - the use of poultry vaccines to control HPAI H5 (see USDA Bans Import Of French Poultry Over HPAI Vaccine Concerns), it is worth looking back at the experience of those countries that have been using these methods for almost two decades.

The two biggest consumers of poultry vaccines over that time have been China and Egypt, with Vietnam, Indonesia, and Hong Kong accounting for a much smaller uptake.

The concern with poultry vaccines is that while they can often prevent symptomatic illness in birds, they don't always prevent infection. That can allow the virus to spread asymptomatically - potentially exposing unwary humans - and the virus may evolve into vaccine-escape strains.

In China, the largest manufacturer and consumer of poultry vaccines, we've seen both successes and failures.

China's massive H5+H7 poultry vaccination program over the summer of 2017 quickly shut down their H7N9 epizootic and seasonal human epidemics (2013-2017) - arguably saved their poultry industry - and also greatly reduced the number of HPAI H5N6 infections for the next several years.

Given how dire the situation was with H7N9, and how close the virus appeared to sparking a human pandemic, this was a remarkable success.

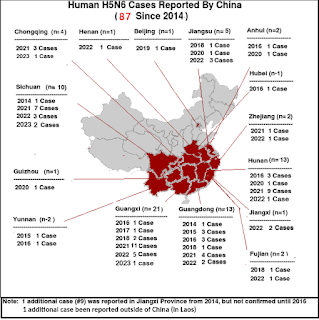

But H5 viruses continues to circulate - apparently asymptomatically in poultry - and H5N6 has spilled over into humans more than 60 times over the past 3 years (see map below).

The failure of vaccination might be because of inefficient application, low dose, and low vaccination coverage (especially in the household sector).11,12 Moreover, the continuing transmission in combination with the intensive long-term usage of the inactivated virus vaccine may have led to antigenic changes leading to immune escape.

Arguably, poultry vaccination in Egypt has been even more problematic. In 2012 we looked at a study (see Egypt: A Paltry Poultry Vaccine) that examined the effectiveness of six commercially available H5 poultry vaccines then being used in Egypt. Of those, only one (based on a locally acquired H5N1 seed virus) actually appeared to offer protection.

In 2018, a follow up study (see Sci. Reports: Efficacy Of AI Vaccines Against The H5N8 Virus in Egypt), indicated that very little had changed in 6 years.

Despite their heavy reliance on vaccines (albeit often of dubious quality), new reassortant HPAI viruses continue to emerge from the region. In the spring of 2019, a new, novel H5N2 appeared in Egypt (see Viruses: A Novel Reassortant H5N2 Virus In Egypt), which identified it as clade 2.3.4.4.

Eight months later, yet another novel H5N2 (a reassortment of H5N8 & H9N2) was described in the EID Journal (see Novel Reassortant HPAI A(H5N2) Virus in Broiler Chickens, Egypt).While a properly applied, well-matched, and frequently updated poultry vaccination program should be an effective strategy against avian flu - at least in captive birds - far too often less rigorous standards have prevailed.

All of which brings us to a lengthy, cautionary and informative review - published in the journal Viruses - on Egypt's poultry vaccination journey which began in 2006.

Open Access Review

Ahlam Alasiri 1,†, Raya Soltane 1,†, Akram Hegazy 2 Ahmed Magdy Khalil 3,4, Sara H. Mahmoud 5,Ahmed A. Khalil 6 Luis Martinez-Sobrido 3,* and Ahmed Mostafa 3,5,*

Vaccines 2023, 11(11), 1628; https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines11111628Received: 24 August 2023 Published: 24 October 2023

Abstract

Despite the panzootic nature of emergent highly pathogenic avian influenza H5Nx viruses in wild migratory birds and domestic poultry, only a limited number of human infections with H5Nx viruses have been identified since its emergence in 1996. Few countries with endemic avian influenza viruses (AIVs) have implemented vaccination as a control strategy, while most of the countries have adopted a culling strategy for the infected flocks.

To date, China and Egypt are the two major sites where vaccination has been adopted to control avian influenza H5Nx infections, especially with the widespread circulation of clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 viruses. This virus is currently circulating among birds and poultry, with occasional spillovers to mammals, including humans.

Herein, we will discuss the history of AIVs in Egypt as one of the hotspots for infections and the improper implementation of prophylactic and therapeutic control strategies, leading to continuous flock outbreaks with remarkable virus evolution scenarios.

Along with current pre-pandemic preparedness efforts, comprehensive surveillance of H5Nx viruses in wild birds, domestic poultry, and mammals, including humans, in endemic areas is critical to explore the public health risk of the newly emerging immune-evasive or drug-resistant H5Nx variants.

(SNIP)

In Egypt, the HPAI H5N1 was documented in domestic poultry in early 2006 (Figure 3) shortly after its detection in wild migratory birds in Damietta Governorate in late 2005 [22]. This virus continued to circulate, leading to accumulated amino acid substitutions in the surface immunogenic glycoproteins (HA and NA), and the virus was declared as endemic in Egypt in 2008 [17,23]. From late 2009 to 2011, two vaccine-escape H5N1 mutant subclades, namely 2.2.1 and 2.2.1.1, co-circulated and were detected in poultry [17].

6. Conclusions and PerspectivesDespite the fact that the risk of H5Nx virus transmission to the public is still low, close monitoring of these AIVs and persons exposed to them is imperative [275]. These AIVs are continuously evolving in endemic areas with improper control plans in place, and under inadequate immune and drug pressures.Taking into consideration the COVID-19 scenarios and the evolution of immunoescape variants in certain geographical areas, followed by the devastating spatiotemporal transmission of these SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern (VoCs) in a few days/months to all continents, we urge global health systems within the “One Health” approach to detect signals of potential variants of interest (VOIs) or variants of concern (VOCs) for the newly emerging avian influenza H5Nx viruses and rapidly assess their risk(s).Likewise, the application of evolution-driving control strategies, including vaccination, in certain geographical areas of the world must be subjected to assertive regulations, including safe farming practices and implementation of locally matching vaccine strains, because these viruses can affect the country of origin, neighboring countries, and may pave the way for a devastating pandemic if a virus acquires the minimum essential substitutions that support viral infection and person-to-person airborne transmission. Therefore, international collaboration to implement unified control strategies against AIVs must be urgently established and applied properly among the different sectors of the One Health approach

Although inadequate poultry vaccination campaigns have likely contributed to our current HPAI H5N1 crisis, where we'd be had those vaccines not been used is impossible to know. It is fair to say, however, that their use (proper or otherwise) has consequences.

If we decide to go down the poultry vaccination road, we need to learn from the mistakes of the past 20 years. Poultry vaccines aren't a quick, easy, or cheap fix.

WOAH: Rethinking Avian Influenza Prevention and Control Efforts

The Great Poultry Vaccination Divide

MPR: Poultry AI Vaccines Are Not A `Cure-all’

New Scientist: The Downsides To Using HPAI Poultry Vaccines