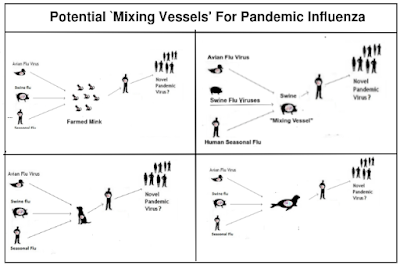

Just a few of many scenarios

#17,758

As the graphic above illustrates, there are a lot of ways that HPAI H5 could reassort into a more dangerous - or more transmissible - virus. Over the past two years we've seen warnings over the virus spreading - and mutating - in mink (and other fur) farms, in marine mammals, and even in swine herds.

Swine served as reassortment hosts for the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus, but the origins of the 1968 (H3N2) and 1957 (H2N2) pandemic viruses remain murky.

Both involved a reassortment of a novel flu virus (avian H2 in 1957 and avian H3 in 1968) with the current human seasonal flu virus (H1N1 in 1957, H2N2 in 1968), producing a novel virus.

We don't know with certainty in what host these reassortments occurred - but since both pandemic viruses were hybrids of seasonal flu and an avian strain - a human host seems likely.

Last week - following CFIA reports of a large number of H5N1 outbreaks at local poultry farms - the BC Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry strongly urged anyone who lived on, or worked at, a poultry farm to get the seasonal flu vaccine.

B.C. poultry staff told to vaccinate against flu as avian strains spread among birds

Poultry workers urged to vaccinate in B.C.

VICTORIA - British Columbia's provincial health officer is urging people living or working on the province's poultry farms to "prioritize" getting influenza vaccinations as avian flu spreads among flocks this fall.

By The Canadian Press

Friday, November 10, 2023

While the seasonal flu vaccine is not designed to prevent H5N1 infection, it can reduce the chances of being infected with seasonal H1N1 or H3N2, thereby lowering the chances of a reassortment event. This vaccination advice is routinely given to people who raise pigs, for very much the same reason.

But of course, it is optional. And in many parts of the world, it isn't even offered.

Over the past couple of decades it has become apparent that humans - much like birds and pigs - can be co-infected with 2 or more flu viruses simultaneously. Up until 2009, human co-infection with influenza A had only rarely been reported.

Dual infections had been noted, but usually with an `A’ and a `B’ virus.

In 2008, we saw a report of an Indonesian teenager who tested positive both H5N1 and the seasonal flu strain H3N2 (see CIDRAP report Avian, human flu coinfection reported in Indonesian teen), demonstrating that co-infection with Influenza A was possible.

But the big breakthrough came in 2009 when the pandemic H1N1 virus emerged and co-circulated for a time with the old seasonal H1N1 virus, allowing scientists in New Zealand to isolate and document 11 cases of Influenza A co-infection (see EID Journal: Co-Infection By Influenza Strains for the full story).

(2019) Eurosurveillance: Novel influenza A(H1N2) Seasonal Reassortant - Sweden, January 2019

(2019) Denmark Reports Novel H1N2 Flu Infection

(2016) J Clin Virol: Influenza Co-Infection Leading To A Reassortant Virus

(2014) EID Journal: Human Co-Infection with Avian and Seasonal Influenza Viruses, China

(2013) Lancet: Coinfection With H7N9 & H3N2

(2011) Webinar: pH1N1 – H3N2 A Novel Influenza Reassortment

Reassortant viruses are undoubtedly far more common than we know, but luckily most don't have the `right stuff' to spread or compete with existing flu viruses. They lack biological `fitness', and usually fade quickly away.

If creating a pandemic virus were easy, we'd be hip deep in them all the time. But every once in a while a novel virus does manage to hit the genetic jackpot, plunging the world into another crisis.

Our ability to prevent the next pandemic is obviously limited, since so much happens out of our sight and beyond our control. But there are places where we can make a difference.

Increased vaccine uptake among farm workers, improved biosecurity, and even closing down some types of operations (e.g. fur farms, live bird markets, etc.) can help reduce the risks from a wide variety of zoonotic threats.

The $64 question is, of course, whether we'll get our act together before the virus does.