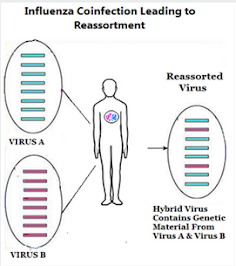

A novel pandemic virus might emerge solely from the wild, but an `easier' route would be for an avian or swine virus to reassort with an already `human-adapted' seasonal flu virus, producing a pandemic inducing hybrid.

While most of these reassortments are evolutionary failures, twice in my lifetime (1957 & 1968) a reassortment between seasonal flu and an avian flu virus - likely in a human host - produced a pandemic virus.

- The first (1957) was H2N2, which According to the CDC `. . . was comprised of three different genes from an H2N2 virus that originated from an avian influenza A virus, including the H2 hemagglutinin and the N2 neuraminidase genes.'

- In 1968 a novel H3N2 virus emerged (a reassortment of 2 genes from a low path avian influenza H3 virus, and 6 genes from H2N2) which supplanted H2N2 - killed more than a million people during its first year - and continues to spark yearly epidemics more than 50 years later.

This is the reason why yearly flu vaccination is strongly recommended for people who raise pigs or work with poultry, and the CDC is now pushing for the vaccination in dairy workers.

Occupational exposure to H5N1 has - at least in the United States - been the primary route of infection, but Friday's announcement of an unrelated case in Missouri is a reminder that past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Only one outlier so far is encouraging, but an absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Particularly when we see reports of sick dairy workers who go untested, and most states relying on voluntary testing of livestock.

Although it is possible that this Missouri infection was a singular event - miraculously picked up (albeit, belatedly) by limited surveillance - past studies strongly suggest we would be lucky to detect 1 in 10 (or even 100) novel flu cases.

- While the 2009 Swine flu pandemic was first reported in Southern California in late April of 2009, we now know the virus had been circulating - unnoticed - for at least 2 months in Mexico (see Early Outbreak of 2009 Influenza A (H1N1) in Mexico Prior to Identification of pH1N1 Virus).

- A study published in 2013 (see CID Journal: Estimates Of Human Infection From H3N2v (Jul 2011-Apr 2012) - estimated that during a time when only 13 cases of novel flu were reported by the CDC - that the actual number of infections was likely 200 times (or more) higher.

- During the opening weeks of China's H7N9 outbreak in 2013, in Lancet: Clinical Severity Of Human H7N9 Infection, we saw estimates that the number of `symptomatic' cases was likely anywhere between 10 and 200 times higher than reported.

- A little over a year ago, we looked at a study from the UK HSA (see UK Novel Flu Surveillance: Quantifying TTD) that estimated the TTD (Time To Detect) a novel H5N1 virus in the community via passive surveillance could take weeks, and the virus might only be picked up after hundreds or possibly even thousands of infections.

Granted, the seasonal flu shot is not expected to provide any protection against the H5N1 virus, but it can help reduce the chances of an individual being simultaneously infected with novel and seasonal flu.

It is admittedly not a perfect solution, since the seasonal flu shot is far better at preventing serious illness than preventing infection. But it is a readily available tool - and given that co-infection might produce more severe illness than seasonal flu alone - having the seasonal vaccine on board may lessen its impact.

And while seasonal vaccine doesn't protect against avian H5N1, it is conceivable (but far from certain) that it might provide some degree of protection against an H5/Seasonal reassortment.

There are plenty of other advantages to getting the seasonal flu vaccine, of course. A few past blogs include:

Nature: Severe Influenza in Pregnancy Linked to Neurodevelopmental Disorders in Offspring

Pediatrics: Maternal Flu Vaccination Extends Protection To Infants

PloS One: Early Risk of Acute Myocardial Infarction Following Hospitalization for Severe InfluenzaCDC: Another Study Linking Severe Influenza To Heart Damage

Sometime the next 30 days I'll roll up my sleeve to get my 19th seasonal flu shot in as many years. In all of that time I've only caught the flu once (summer 2009), before the pandemic H1N1 vaccine was released.

While I recognize it probably only provides my age group with 30%-40% protection, given the long list of things that can go wrong during or following flu infection, I'll take whatever advantage I can get.

And if, perchance, it prevents a pandemic-inducing reassortment with HPAI H5 (not that we'll ever know), so much the better.