Data from this study suggest that there is extremely low to no population immunity to clade 2.3.4.4b A(H5N1) viruses in the United States. Antibody levels remained low regardless of whether or not the participants had gotten a seasonal flu vaccination, meaning that seasonal flu vaccination did not produce antibodies to A(H5N1) viruses.

This means that there is little to no pre-existing immunity to this virus and most of the population would be susceptible to infection from this virus if it were to start infecting people easily and spreading from person-to-person. This finding is not unexpected because A(H5N1) viruses have not spread widely in people and are very different from current and recently circulating human seasonal influenza A viruses.

While H5Nx - should it ever become easily transmissible among humans - would likely find a target-rich environment, there are other studies which suggest there is far more to immunity than just the antibody response.

During the 1918 pandemic, the attack rate is estimated to have been 25%-40%, meaning that > half the world's population did not experience a symptomatic infection, despite frequent exposure.

While influenza often impacts the elderly and the very young the most, the infamous `W Shaped curve' to the 1918 pandemic (see below) shows that young adults (age 20-40) were hit unexpectedly hard.

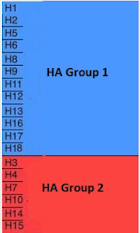

Although a prior H1Nx pandemic (possibly in the 1860s or early 1870s) might account for the lower mortality in those > 60 years, it doesn't explain the dip in 5 to 14 year-olds. More than 100 years after the fact, there remains a lot we don't understand about that pandemic.There is growing evidence to suggest that the first flu HA type (Group 1 or 2) you are exposed to can shape your immune response to influenza for the rest of your life through a process called Original Antigenic Sin (OAS) (see PLoS Path.: Childhood Immune Imprinting to Influenza A).

- Those born prior to the mid-1960s were almost certainly first exposed to Group 1 flu viruses (H1N1 or H2N2)

- Those born after 1968 and before 1977 would have been exposed to Group 2 (H3N2)

- After 1977, both Group 1 and 2 viruses co-circulated, meaning the first exposure could have been to either one.

We last explored this phenomenon last month, in Preprint: Pre-existing H1N1 Immunity Reduces Severe Disease with Cattle H5N1 Influenza Virus, where researchers suggested the reason behind the recent spate of mild H5N1 presentations in the United States may be due to prior exposure to the H1N1 virus.

Last December we saw some speculation that the seasonal flu shot might provide some limited protection, since the the NA (neuraminidase) gene segment in our seasonal H1N1 virus is antigenically similar to the NA gene segment in the clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 virus.

And in last May's Nature Dispatch: Risk Assessment On HPAI H5N1 From Mink, the authors also offered that: While different influenza A virus subtypes are antigenically distinct, some degree of cross-protection against H5N1 may be conferred by prior exposure to these seasonal strains, especially against the N1 neuraminidase.

None of this suggests that an H5N1 pandemic would be mild, only that there could be some small degree of pre-existing immunity among some of the population (note: previous exposure to a similar virus isn't always beneficial, in some cases (such as with dengue) it can even make the second exposure worse.)

All of which brings us to a new preprint which suggests that - in addition to the factors discussed above - that patterns of immunodominance of seasonal flu and H5N1 are similar, and that preexisting T cell immune memory from seasonal influenza may be cross-reactive with the H5N1 virus.

This is a lengthy and complex report, and deserves a full reading. I've only posted the link, abstract, and a brief excerpt below. Follow the link to read it in its entirety.

Targets of influenza Human T cell response are mostly conserved in H5N1John Sidney, AReum Kim, Rory Dylan de Vries, Bjoern Peters, Philip S. Meade, Florian Krammer, Alba Grifoni, Alessandro Sette

doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.09.612060

Abstract

Frequent recent spillovers of subtype H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) virus into poultry and mammals, especially dairy cattle, including several human cases, increased concerns over a possible future pandemic.

Here, we performed an analysis of epitope data curated in the Immune Epitope Database (IEDB). We found that the patterns of immunodominance of seasonal influenza viruses circulating in humans and H5N1 are similar. We further conclude that a significant fraction of the T cell epitopes is conserved at a level associated with cross-reactivity between avian and seasonal sequences, and we further experimentally demonstrate extensive cross-reactivity in the most dominant T cell epitopes curated in the IEDB.

Based on these observations, and the overall similarity of the neuraminidase (NA) N1 subtype encoded in both HPAI and seasonal H1N1 influenza virus as well as cross-reactive group 1 HA stalk-reactive antibodies, we expect that a degree of pre-existing immunity is present in the general human population that could blunt the severity of human H5N1 infections.

Based on this analysis and the overall information available to date, we hypothesize that, should a widespread HPAI H5N1 outbreak in humans occur, cross-reactive T cell responses might be able to limit disease severity, but to a lower extent than what was observed in the context of 2009 pH1N1. We propose that a strategy to enhance and focus T cell immunity towards recognition of conserved and immunogenic regions within a virus family might be generally applicable to several families of potential pandemic concern73 . We submit that this strategy might also be applicable in the case of the pandemic threat of influenza.

Exactly how much of an advantage pre-existing cross-reactive T Cells might provide is unknown, but even a little dampening effect might make the difference between a moderately severe flu and a fatal one.

But even a more reasonable 2%-5% CFR would present a public health crisis unlike anything we've seen in the modern era. So any edge provided by preexisting cross-reactive T Cells, or prior influenza infection or vaccination, could have a huge impact.