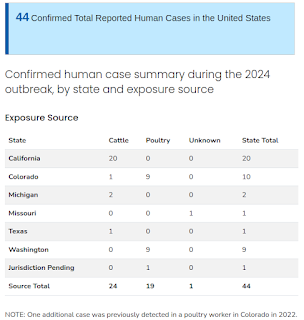

The 44 cases include 20 cases in dairy farm workers in California, three of which were confirmed by CDC last week and three on Monday, November 4; nine cases in poultry farm workers in Washington state, three of which were confirmed by CDC last week; and one case associated with the Washington poultry outbreak that was confirmed by CDC last week and is pending jurisdiction assignment. Not included in that count are four probable cases -- one in a California dairy farm worker and three in Washington state poultry farm workers. While these probable cases were negative on confirmatory testing at CDC, all four met the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) probable case definition and have been reported by the states.

While it would be nice to have agreement, the reality is both numbers are likely significant undercounts.

We've seen anecdotal reports of symptomatic farm workers who refused testing (see EID Journal: Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Virus among Dairy Cattle, Texas, USA), and our influenza surveillance systems are unlikely to pick up non-hospitalized cases.

In their weekly laboratory update, the CDC reports:

Laboratory Update

CDC posted a spotlight describing the results of CDC's first study investigating the effects in ferrets of an avian influenza A(H5N1) virus isolated from a human case in the United States. The study, published on October 28 in the journal Nature, found that when 12 laboratory ferrets were infected with a virus isolated from a human case in Texas (A/Texas/37/2024), all 12 experienced severe and fatal disease. The study also found that this virus efficiently transmitted from infected ferrets to healthy ferrets in the presence of direct contact and, less efficiently, via fomites and respiratory droplets. Preliminary findings from this study, first shared in June 2024, were instrumental in informing early risk assessments related to this outbreak.

To date, CDC has confirmed nine human cases of H5 bird flu i,n poultry farm workers in Washington state. Genetic sequencing of three of these cases confirms that all are avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses from clade 2.3.4.4b and that all are closely related genetically to the viruses causing infections in poultry on the farm where depopulation was conducted. CDC has successfully obtained partial gene sequences for viruses from three cases in Washington (A/Washington/239/2024, A/Washington/240/2024, A/Washington/247/2024) with other cases pending sequence analysis.

That sequencing information showed that the viruses' hemagglutinin (HA) is closely related to candidate vaccine viruses (CVV) and that there were no changes in the HA associated with increased infectivity or transmissibility among people. Additionally, there were no mutations associated with reduced susceptibility to available neuraminidase inhibitor treatments and no mutations identified in other genes indicating additional mammalian adaptation. Genetic data have been posted in GISAID and GenBank. Additional data will be posted as they become available. CDC has successfully isolated virus from specimens from three of the nine cases. Attempts to isolate virus from additional specimens are ongoing. Antigenic characterization and antiviral susceptibility testing are underway. Antigenic characterization will inform whether existing H5 bird flu candidate vaccine viruses (CVVs) would provide good inhibition of these viruses.

Although much of our attention this summer has been focused on the `bovine' B3.13 genotype which has infected hundreds of dairy herds, some poultry flocks, and has spilled over into at least 24 humans - over the past couple of weeks we've seen the emergence of 2 new genotypes; D1.1 and D1.2.

According to a brief statement (below) from the USDA, the Oregon poultry & swine outbreak of H5N1 was due to genotype D1.2, while the week before we learned that the Washington state outbreak (and spillover into humans) was from genotype D1.1.

A reminder that H5N1 is not a single viral threat, but rather represents a large and growing array of similar viruses all following their own evolutionary pathways. Additionally, we continue to watch other H5 subtypes (H5N5, H5N6, H5N2, etc.), which also have zoonotic potential.

You'll find more details on the above mentioned ferret study in Saturday's blog `CDC: Updated Results On Texas H5N1 Virus In Ferrets'.

The CDC also addresses the other big H5 story from last week, the first detection of H5N1 in a pig in the United States.

Epidemiology Update

On Wednesday, October 30, 2024, USDA reported an avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in a pig on a backyard farm in Oregon. This is the first time an H5 bird flu infection has been reported in a pig in the United States. Sequence data from birds in the avian influenza A(H5) virus outbreak on this backyard farm showed no mutations that caused concerns related to disease severity or adaptability to humans.The discovery that an avian influenza A virus has infected a new mammal species is always concerning, especially when the virus is detected in pigs, which are susceptible to influenza viruses circulating in pigs, humans, birds, and other species. These viruses can swap genes through a process called genetic reassortment, which can occur when two (or more) influenza viruses infect a single host. Reassortment can result in the emergence of new influenza A viruses with new or different properties, such as the ability to spread more easily among animals or people. Reassortment events have happened in pigs in the past. A series of reassortment events in pigs is believed to have caused the 2009 influenza A(H1N1) pandemic. Based on available information, the risk to the general public remains low; however, CDC is continuing to gather information.

A multilingual CDC field team continues to assist the California Department of Public Health in its efforts to learn more about how the outbreak in California began and how to lower the risk to farm workers with exposure to infected cows. Two staff members are on the ground in California, and additional staff are ready to deploy if needed. CDC staff are assisting with active surveillance efforts, including field assessments of suspected cases and household contacts; testing and treatment; and dissemination of information to farm workers and the community. A separate CDC field team has returned from deployment to Washington state but continues to work remotely with the local health department on data management and epidemiological summaries. There is no evidence of any person-to-person spread in either of the two states or anywhere in the United States.

I've only posted some highlights, follow this link to read the full update.

As the CDC states, the detection of H5 in a pig in the United States is concerning, since swine are susceptible to human, swine, and avian flu viruses and have demonstrated the ability to generate reassortments in the past.

The Oregon spillover is on a small, non-commercial farm - and is likely a dead-end - but other spillovers into larger swine herds are possible. Complicating matters, H5N1 in pigs is often asymptomatic, which makes it more difficult to detect.

A few past blogs on this topic include:

Emerg. Inf. & Microbes: Pigs are Highly Susceptible To But Do Not Transmit Mink-Derived HPAI

EID Journal: Divergent Pathogenesis and Transmission of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza A(H5N1) in Swine

Seroconversion of a Swine Herd in a Free-Range Rural Multi-Species Farm against HPAI H5N1 2.3.4.4b Clade Virus (2023)

Sci. Rpts.: Evidence Of H5N1 Exposure In Domestic Pigs - Nigeria (2018)

For more on all of this, yesterday C Raina MacIntyre and Haley Stone published an informative article in The Conversation on: