Reasons Given Not To Get the Seasonal Flu Vaccine

#18,248

For those of us who loiter in the echo chamber of emerging infectious diseases, emergency preparedness, or who work in certain farming sectors, HPAI H5Nx is a legitimate public health concern; and while not guaranteed to spark the next pandemic, it is plausible contender.

But for the vast majority of people - even those who watch the news or scroll social media - it is just one of hundreds of annoying threats they are incessantly bombarded with each and every day.

In a clickbait driven economy - where the `truth' often depends upon the teller's agenda, and headlines are usually either hyperbolic or deceptive - for many it has become preferable to be selective consumers of information, while tuning out everything else.

If Timothy Leary's "Turn on, tune in, drop out" was the catch-phrase of my youth then `Turn off, tune out, and drop dead!' may well be the anthem for today.

At least, that might help explain the results of two recent surveys that examine the public's perception of the risks of avian influenza in the United States, and seasonal flu vaccine uptake among poultry workers in the UK.

Our first stop is an editorial in the American Journal of Public Health, which alas, is mostly behind a pay wall. We do, however, has a press release with many of the details.

Rachael Piltch-LoebPhD, MSPH , Katarzyna WykaPhD , Trenton M. WhitePhD, MPH , Shawn G. GibbsPhD, MBA, CIH , Sara GormanPhD , Ashish JoshiPhD, MBBS, MPH , Spencer KimballJD , Jeffrey V. LazarusPhD, MIH, MA , John J. LowePhD , Kenneth RabinPhD , Scott C. RatzanMD , and Ayman El-MohandesMBBCh, MD, MPH

News Release 17-Apr-2025

CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy

April 17, 2025 - In an editorial in the American Journal of Public Health, a team led by researchers from the CUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy (CUNY SPH) say public ignorance and apathy towards bird flu (highly pathogenic avian influenza, or HPAI) could pose a serious obstacle to containing the virus and preventing a larger-scale public health crisis.

The authors, including CUNY SPH Assistant Professor Rachael Piltch-Loeb, Associate Professor Katarzyna Wyka, Professor Jeffrey V. Lazarus, Senior Scholar Kenneth Rabin, Distinguished Lecturer Scott C. Ratzan, and Dean Ayman El-Mohandes, conducted a population representative survey of U.S. residents from August 5 to 15, 2024, which used an in-depth sampling framework and intentional oversampling of rural populations.

The results suggest many respondents were unaware of simple food safety practices that could reduce the risk of HPAI infection. Over half (53.7%) did not know that pasteurized milk is safer than raw milk, although almost three of four respondents (71.3%) did understand that cooking meat at high temperatures could eliminate harmful bacteria and viruses like H5N1.

Over a quarter (27%) of respondents said they were unwilling to modify their diet to reduce the risk of exposure to the virus, and more than one in four respondents (28.7%) expressed reluctance to take a potential vaccine for H5N1, even if advised by the CDC to do so.

Participants who described themselves as Republicans or Independents were significantly less likely than Democrats to support either vaccination or dietary modifications.

Rural Americans, many of whom are more likely to work or live in or near livestock industries, were less likely to accept public health measures, including vaccination and dietary changes, compared to their urban counterparts.

“These attitudes could pose a serious obstacle to containing the virus and preventing a major public health crisis,” says Piltch-Loeb, the study’s lead author. “The fact that responses vary significantly by political party and geography emphasizes the need for a carefully segmented health communications strategy to address the issue.”

Rabin, who has been engaged in health communications campaigns for more than four decades, adds that, “Working closely with agricultural leaders, farm communities and food processing companies will be critical, and the fact that most of the agricultural workers who are at direct risk of exposure to the bird flu virus may be undocumented could seriously jeopardize efforts to track and control the spread of infections.”

Media contact:Ariana CostakesCommunications Editorial ManagerCUNY Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy (CUNY SPH)

Our second stop is a study, published this past week in the journal Influenza & Other Respiratory Viruses, which surveyed hundreds of poultry workers in the UK on their attitude towards - and uptake of - seasonal flu vaccines in light of the growing HPAI H5 threat.

In the United States, Canada, the UK, and many European countries it is recommended that those who work with poultry or swine (and cattle in the U.S.) get the seasonal flu vaccine, even though it is not designed to protect against avian or swine influenza viruses.

Admittedly, we've seen some (slight) evidence that seasonal flu vaccination might provide some degree of protection against a severe or fatal H5Nx infection, including:

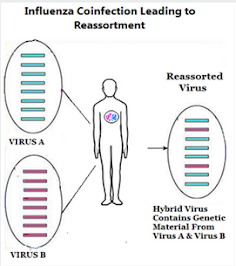

Effect of Prior Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 Virus Infection on Pathogenesis and Transmission of Human Influenza A(H5N1) Clade 2.3.4.4b Virus in Ferret ModelBut the big concern is a farm worker might be exposed to HPAI H5 (or swine flu) while concurrently infected with seasonal flu, setting up the potential for a reassortment event (see Preprint: Intelligent Prediction & Biological Validation of the High Reassortment Potential of Avian H5N1 and Human H3N2 Influenza Viruses).

Influenza A(H5N1) Immune Response among Ferrets with Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 Immunity

Twice in my lifetime (1957 and 1968) avian flu viruses have done exactly that; reassorted with seasonal flu and launched a human pandemic.

- The first (1957) was H2N2, which According to the CDC `. . . was comprised of three different genes from an H2N2 virus that originated from an avian influenza A virus, including the H2 hemagglutinin and the N2 neuraminidase genes.'

- In 1968 an avian H3N2 virus emerged (a reassortment of 2 genes from a low path avian influenza H3 virus, and 6 genes from H2N2) which supplanted H2N2 - killed more than a million people during its first year - and continues to spark yearly epidemics more than 50 years later.

Despite the UK government's recommendations, the following survey reveals disappointing levels of seasonal flu vaccine uptake (35%) among poultry workers in the UK. Since this survey was voluntary, there may be some bias to these numbers, so these results should be taken with a grain of salt.

Seasonal Influenza Vaccination in People who Have Contact With Birds

Amy Thomas, Suzanne Gokool, Harry Whitlow, Genevieve Clapp, Peter Moore, Richard Puleston, Louise E. Smith, Riinu Pae, Ellen Brooks-Pollock

First published: 19 April 2025 https://doi.org/10.1111/irv.70101

Funding: Funding for the Avian Contact Study was awarded by PolicyBristol from the Research England QR Policy Support Fund (QR PSF) 2022-24 for investigating ‘Zoonotic spillover of avian influenza’. AT is funded by the Wellcome Trust, Early Career Award [227041/Z/23/Z].

ABSTRACT

Background

Following the 2021–2022 avian influenza panzootic in birds and wildlife, seasonal influenza vaccines have been advised to occupationally high-risk groups to reduce the likelihood of coincidental infection in humans with both seasonal and avian influenza A viruses.

Methods

We developed and launched a questionnaire aimed at poultry workers and people in direct contact with birds to understand awareness and uptake of seasonal influenza vaccination. We collected responses in-person at an agricultural trade event and online.

Findings

The questionnaire was completed by 225 individuals from across the United Kingdom. The most commonly reported reason for vaccination was protection against seasonal influenza (82%, 63 of 77). Nearly, all individuals aged ≥65 years reported that the vaccine was recommended for them (24 of 28).

There was no difference in recommendation for occupational groups. Most vaccinees were aged over 60 years (60%, 29 of 48); however, coverage was lower than expected in the ≥ 65 target group.

Vaccination in those exposed to avian influenza was low (32%, 9 of 28). Not having enough time was the single most reported reason for not getting vaccinated in those intending to. Individuals unintending to be vaccinated perceived natural immunity to be better than receiving the vaccine as well as lack of awareness and time.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that targeted campaigns in occupationally exposed groups need to be undertaken to improve communication of information and access to vaccine clinics. We recommend co-production methods to optimise this public health strategy for increased knowledge and future vaccine uptake.

(SNIP)

A complete description of methods, public involvement and participant demographics can be found in the Data Note [22]. A total of 225 people took part in the study between May to July 2024, two respondents were excluded from all analyses as they did not provide responses to at least one vaccine question, and one participant did not complete the gender question. Briefly, most respondents were male (63%, 140 of 222; female 37%, 82 of 222) and between 30 to 59 years (69%, 153 of 222). Male respondents had a higher median age than female respondents (52 compared to 44 years) (Figure 1a). Poultry farmer was the most frequently reported occupation (72%, 102 of 222), followed by veterinarian, zookeeper and poultry manager (Figure 1b).

Details are in the caption following the image

FIGURE 1

Distribution of respondent age, gender and occupation (a) Age distribution of respondents grouped by gender—female in red and male in blue (note one ‘Other’ and one NA response not plotted). (b) Top 4 occupations reported (occupations with fewer than five observations grouped with ‘Other’).

(SNIP)

Overall, 35% of respondents (77 of 223) had been vaccinated against seasonal influenza, of these 79% (61 of 77) had the vaccine provided by the NHS and a further 21% paid for the vaccine themselves (16 of 77). Most individuals did not intend to receive the vaccine (44%, 98 of 223), while 11% (25 of 223) had not been vaccinated but intended to and 10% (22 of 223) did not know.

Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake increased with increasing age; the greatest proportion of vaccinees (60%, 29 of 48) were aged ≥ 60 years (Figure 2c). Conversely, younger age groups were less likely to be vaccinated, with the largest unvaccinated proportion (66%, 45 of 68) aged between 20–39 years (Figure 2c).

As we discussed several months ago in The Wrong Pandemic Lessons Learned, we seem to be less well prepared today for another pandemic than we were a decade ago.

While we may get lucky and have years before seeing another pandemic, at some point our luck will run out (see BMJ Global: Historical Trends Demonstrate a Pattern of Increasingly Frequent & Severe Zoonotic Spillover Events).Our collective trauma following years of COVID, the travails of navigating day-to-day life, and inconsistent messaging (and actions) from governments and health authorities, have left society both numb and vulnerable.