#18,739

For many years it was common to hear that - of all the diseases with pandemic potential - it was influenza A that kept virologists up at night. A little over 20 years ago, the emergence of SARS-CoV forced the addition of novel coronaviruses to that short list.

In 2017 (and again in 2018) the WHO released a list (n=8) of priority diseases (see WHO List Of Blueprint Priority Diseases) - that in their estimation had the potential to spark a public health emergency and were in dire need of accelerated research:

Last summer the WHO unveiled an expanded 38-page Pathogens Prioritization report, increasing the number of priority pathogens to more than 30. Additions included 7 different influenza A subtypes (H1, H3, H3, H5, H6, H7, and H10), and 5 bacterial strains that cause cholera, plague, dysentery, diarrhea and pneumonia.

- Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF)

- Ebola virus disease and Marburg virus disease

- Lassa fever

- Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

- Nipah and henipaviral diseases

- Rift Valley fever (RVF)

- Zika

- Disease X

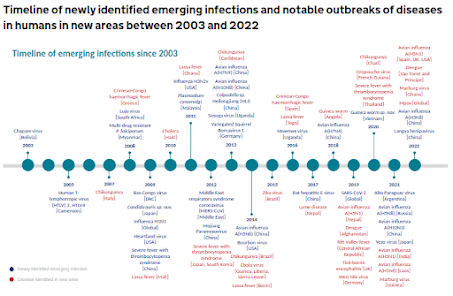

Thirty years ago researcher George Armelagos of Emory University posited that since the mid-1970s the world had entered into an age of newly emerging infectious diseases, re-emerging diseases and a rise in antimicrobial resistant pathogens (see The Third Epidemiological Transition (Revisited).

- Picornaviridae (e.g. rhinoviruses, EV-71, EV-D68, etc)

- Paramyxoviridae (e.g. HPIV, Nipah, measles, etc.)

- Adenoviridae (e.g. Ad14, Ad7)

- Pneumoviridae (e.g. Metapneumovirus, hRSV, etc.)

Although there are certainly other viral families with pandemic potential, the authors of this perspective focus on viruses which currently have limited or no medical countermeasures (MCMs). While it's not a long article, I've only posted a few excerpts.

Follow the link to read it in its entirety. I'll have a bit more after the break.

Viral Families with Pandemic Potential

Open Access

Amesh Adalja, MD FIDSA , Thomas Inglesby, MD

Open Forum Infectious Diseases, ofaf306, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaf306

Published: 26 May 2025 Article history

A major challenge of pandemic preparedness is how to anticipate and prepare for future pandemic threats among the wide range of viral threats that can infect humans. Fortunately, only a subset of the 25 viral families that can infect humans have both the capability of widespread respiratory transmission in humans or animals, a prerequisite for pandemic-causing capability, as well a lack of medical countermeasures (MCMs) to prevent and treat the key viral species within them.

Orthopoxviruses, for example, clearly have historically shown the capacity to cause terrible pandemics in humans, but there exist vaccines and antivirals that have been developed and stockpiled for this viral family that are cross protective against multiple family members (unlike the case for the pandemic-causing orthomyxoviruses and coronaviruses).

Therefore, for the purposes of identifying novel rapid-onset novel pandemics, they are not listed here as a viral family of pandemic potential with unmet R&D requirements though there is clear need for improved countermeasures to both of these viral families.

Prior to COVID, most pandemic preparedness efforts, when they did occur, focused almost exclusively on influenza viruses. Pandemic preparedness was considered to be nearly synonymous with influenza preparedness. This has basis in experience as the only occurring pandemics for almost a century (spanning from at least 1918 to 2009) were all caused by influenza A viruses. However, a number of events of the past 20 years have shown the capacity of coronaviridae to cause major epidemics and pandemics: SARS—CoV-1 in 2003, MERS-CoV in 2012, and, most recently and obviously, SARS-CoV-2 in 2019-2020.

It is critical now to plan for other viral threats that can cause huge epidemics or pandemics. We were one of the first to publish on the characteristics of pandemic pathogens, and in that effort, we emphasized conceptualizing the problem by putting specific focus on viral families of greatest pandemic potential, particularly families for which no MCMs were yet developed [1,2].

- EID Journal: Henipavirus in Northern Short-Tailed Shrew, Alabama, USA

- EID Journal: Emerging Enterovirus A71 Subgenogroup B5 Causing Severe Hand, Foot, and Mouth Disease, Vietnam, 2023

- India: Media Reports Of A Large Surge In Pediatric Adenovirus Infections

- NEJM: A Novel Henipavirus With Human Spillover In China

- mBio: Contemporary EV-D68 Strains Have Acquired The Ability To Infect Human Neuronal Cells

BMJ Global: Historical Trends Demonstrate a Pattern of Increasingly Frequent & Severe Zoonotic Spillover Events

PNAS Research: Intensity and Frequency of Extreme Novel Epidemics

Which means that while we can try to ignore these threats, at some point time our luck - and time - will run out.