Photo Credit Wikipedia

# 8704

Although we’ve seen numerous warnings from public health agencies about the dangers of consuming undercooked poultry products in those areas of Asia and the Middle East where H5N1 is endemic, most of the evidence for that risk has been anecdotal. We’ve seen a relatively small number of human H5N1 infections where consumption of undercooked poultry, or raw duck blood pudding, was been strongly suspected as the route of infection.

Poultry and eggs are considered safe if handled and cooked properly. Consumption of raw blood pudding (duck or pig), a delicacy in Asia, is probably never a good idea as it carries other additional risks, including Strep Suis infection (see A Streptococcus suis Round Up).

.

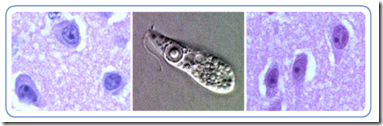

In 2010, we saw a study (see H5N1 Can Replicate In Human Gut) that provided additional evidence that the bird flu virus can thrive in the human gastrointestinal system. Researchers found that Avian Influenza A(H5N1) Viruses Can Directly Infect and Replicate in Human Gut Tissues.

We’ve also seen numerous reports over the years of cats infected with the H5N1 virus after consuming infected birds. The following comes from a World Health Organization GAR report from 2006.

H5N1 avian influenza in domestic cats

28 February 2006

(EXCERPTS)

Several published studies have demonstrated H5N1 infection in large cats kept in captivity. In December 2003, two tigers and two leopards, fed on fresh chicken carcasses, died unexpectedly at a zoo in Thailand. Subsequent investigation identified H5N1 in tissue samples.

In February 2004, the virus was detected in a clouded leopard that died at a zoo near Bangkok. A white tiger died from infection with the virus at the same zoo in March 2004.

In October 2004, captive tigers fed on fresh chicken carcasses began dying in large numbers at a zoo in Thailand. Altogether 147 tigers out of 441 died of infection or were euthanized. Subsequent investigation determined that at least some tiger-to-tiger transmission of the virus occurred.

In 2006, Dr. C.A. Nidom demonstrated that of 500 cats he tested in and around Jakarta, 20% had antibodies for the bird flu virus. And in 2007 the FAO warned that: Avian influenza in cats should be closely monitored, although so far no sustained virus transmission in cats or from cats to humans has been observed.

Dogs are not exempt, as in 2006 the EID Journal published a Dispatch Fatal Avian Influenza A H5N1 in a Dog that documented a a fatal outcome following ingestion of an H5N1-infected duck in Thailand in 2004.

In 2011 we looked at a study that examined Gastrointestinal Bird Flu Infection In Cats, and as recently as 2012 the OIE reported on Cats Infected With H5N1 in Israel.

All of which brings us to a new short report that appears in Veterinary Research, that attempts to quantify the viral dose needed to infect ferrets through ingestion of infected meat. First the link and abstract (the entire study is available), and an excerpt from the Discussion, then I’ll be back with a little more.

High doses of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in chicken meat are required to infect ferrets

Kateri Bertran and David E Swayne

For all author emails, please log on.

Veterinary Research 2014, 45:60 doi:10.1186/1297-9716-45-60

Published: 3 June 2014

Abstract (provisional)

High pathogenicity avian influenza viruses (HPAIV) have caused fatal infections in mammals through consumption of infected bird carcasses or meat, but scarce information exists on the dose of virus required and the diversity of HPAIV subtypes involved. Ferrets were exposed to different HPAIV (H5 and H7 subtypes) through consumption of infected chicken meat.

The dose of virus needed to infect ferrets through consumption was much higher than via respiratory exposure and varied with the virus strain. In addition, H5N1 HPAIV produced higher titers in the meat of infected chickens and more easily infected ferrets than the H7N3 or H7N7 HPAIV.

The complete article is available as a provisional PDF. The fully formatted PDF and HTML versions are in production.

Discussion

In conclusion, relatively high concentrations of H5N1 HPAIV are required to produce infection and death by consumption of infected meat in ferrets as compared to respiratory exposure. Ingestion of HPAIV-infected meat can produce infection that primarily involves the respiratory tract but can also spread systemically depending on both the virus strain and virus dose received. Although human infections by HPAIV through direct oral contact have been occasionally reported [12,13], airborne virus or contact with fomites is still considered the main route of exposure in human species [1].

Essentially researchers used 9 ferrets per virus tested, dividing them into three groups; low dose, medium dose, and high dose. They then compared morbidity, and mortality, seroconversion rates, and finally necropsy and histopathology test results to determine which viruses were able to infect via the oral consumption route, their effects, and how much of a viral load was required.

H5N1 viruses tended to replicate to higher titers in poultry meat than did the H7 viruses tested, and therefore were more infectious.

Interestingly (but not surprisingly), there was a good deal of variability in the ferret outcomes between the two HPAI H5N1 strains (Mong/05 & VN/04) tested. None of the Mong/05 infected ferrets died, and most showed little or no signs of illness. Seven of nine seroconverted. Two of the VN/04 infected ferrets died, while two other seroconverted.

As this study illustrates, different clades of the H5N1 virus often demonstrate different degrees of virulence, something we looked at back in 2012 in Differences In Virulence Between Closely Related H5N1 Strains.

With the caveat that it is always a bit perilous to transpose animal study results to humans, this study supports the notion that consumption of improperly cooked avian-flu-infected poultry products could be reasonably assumed to pose a health risk.

The good news, at least for ferrets, is that it takes a fairly large helping, and the `right’ strain of virus, to prove fatal.