# 6017

Last January I wrote of my elderly father’s brush with pneumonia last Christmas, and the steps we had taken in advance to make sure his wishes were respected regarding his treatment.

I’m happy to say, he survived that bout, and is still with us, having recently celebrated his 87th birthday.

This week, another family member living in another state – also in her mid-80s – underwent major lung surgery, and her recovery is apparently not going well.

While her children believe she would not want heroic measures taken at this point (i.e. life support), she is - at least for now - unable to make her wishes known, and they are without legal guidance.

Her children are now scrambling to see if they can find a living will, or if she had assigned a health proxy (things she should have done pre-surgery), all the while being faced with making increasingly difficult medical decisions.

I don’t know how this medical drama is going to turn out, but I do know that this angst ridden family vignette is replayed in hundreds of hospital waiting rooms every day in this country.

Frankly, this is a conversation – and a legal matter – that everyone needs to deal with before they end up in a hospital, or on an operating table.

While perhaps not the happiest of yuletide conversations - this is the time of year when many families get together - and that makes it a perfect time to get your family’s affairs in order.

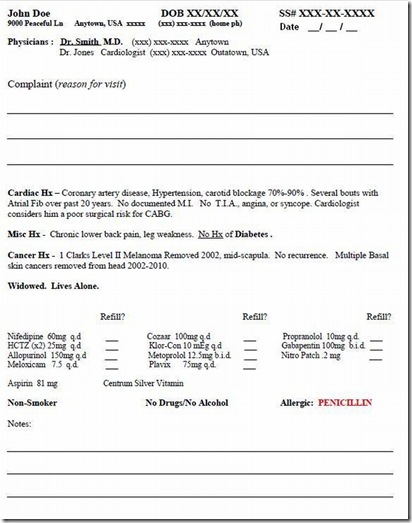

That means updated family and medical histories on everyone (see A Family Affair), and putting together the legal documents to ensure your wishes are respected should you be unable to direct the course of your own care.

With that in mind, below you’ll find a reprint of a blog from last January, on living wills, health care proxies, and DNR orders.

On Having `The Conversation’

(First printed 01/03/11)

I don’t generally put personal anecdotes in my blog because . . . well, I’m really not all that interesting. But today, an exception.

My father, who turned 86 last November and now lives with my sister in another town, contracted a serious respiratory infection over the Christmas holidays. By late last week he was in pretty rough shape with wheezing, shortness of breath, weakness, and violent coughing.

My sister took him to his doctor, who fearing Dad had pneumonia, wanted to hospitalize him.

Dad refused. Adamantly.

All Dad really wanted was to go back to his own bed. If something `bad’ happened, he said, so be it. Better at home than in some strange hospital.

His doctor, after several futile attempts to talk him into going to the hospital, gave up. She wrote him an Rx for Zithromax, and let him go home with the promise that if he got worse over the weekend, he’d go to the emergency room.

Dad muttered a diplomatic, but completely non-binding, “We’ll see.”

I am pleased to tell you that the worst did not happen, and Dad is doing much better after 5 days at home on an antibiotic.

But, as Dad is quick to remind people, when you are 86 years of age – and have the kinds of health problems he has - you really shouldn’t be buying any green bananas.

Dad has serious (and inoperable) coronary and carotid artery issues, has had several serious bouts with cancer, lives with chronic back & hip pain, and his quality of life is continually declining.

Dad believes he is approaching the end of a long road, and feels no need to take extraordinary steps to prolong that journey beyond whatever nature intends. He’s made that abundantly clear to his kids, his doctors, and to anyone else who will listen.

Which is why Dad, my sister and I have had `the conversation’.

We’ve discussed, in detail, exactly what Dad would want us to do if he were unable to make medical decisions for himself.

In fact, a few months ago Dad asked if I would get for him a legally binding Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order, so that if something happened to him, and an ambulance were called, no heroics would be performed.

Verbal instructions by family members – even if the patient is in the last stages of an incurable illness – are likely to be ignored by emergency personnel.

Dad now proudly has the bright yellow DNR order posted over his bed, and carries another credit-card sized one in his wallet.

In Florida, the form must be printed on yellow paper. Different states have different requirements. You should check with your doctor, or the local department of health to determine what the law is in your location.

My twin brother and I, both former paramedics (hey, it was a hereditary defect), and my sister fully support Dad’s decision to have a DNR.

We’ve also had (for many years) a living will and a Health Care Proxy drawn up for Dad, so either my sister or I can make decisions regarding Dad’s health care should he no longer be able to.

As an aside, I’ve had a living will and an assigned Health Care Proxy in place for decades, to ensure that my wishes would be respected if I were suddenly unable direct my medical care.

Frankly, I consider them absolutely essential for all adults to have.

These are difficult subjects for many people to discuss, and so far too often, they get put aside until it is too late. But better to talk about it now, and to have the proper papers in place, than to face a family medical crisis unprepared.

As a former medic, I’ve seen the anguish that relatives have suffered trying to make a life or death decision without input from the patient.

And I’ve also seen what happens when family members argue over what should be done about a loved one on life support. These are deeply emotional issues, and can create life-long rifts in the fabric of families.

While nothing can eliminate the emotional trauma that comes with a medical crisis, making rational decisions now – and making them known and binding – can greatly reduce the strain later.

Take my advice. Whether you want heroic measures taken, or not.

Make your wishes known.

Have the conversation.