Note: This post is essentially an updated version of last year’s National Family History Day blog entry.

# 8006

Every year since 2004 the Surgeon General of the United States has declared Thanksgiving – a day when families traditionally gather together - as National Family History Day.

As a former paramedic, I am keenly aware of how important it is for everyone to know their personal and family medical history. Every day emergency room doctors are faced with patients unable to remember or relay their health history during a medical crisis. And that can delay both diagnosis and treatment.

Which is why I keep a medical history form – filled out and frequently updated – in my wallet, and have urged (and have helped) my family members to do the same.

The CDC and the HHS have a couple of web pages devoted to collecting your family history, including a web-based tool to help you collect, display, and print out your family’s health history.

Family History: Collect Information for Your Child's Health

Surgeon General's Family Health History Initiative

Using this online tool, in a matter of only a few minutes, you can create a basic family medical history. But before you can do this, you’ll need to discuss each family member’s medial history. The HHS has some advice on how to prepare for that talk:

Before You Start Your Family Health History

Americans know that family history is important to health. A recent survey found that 96 percent of Americans believe that knowing their family history is important. Yet, the same survey found that only one-third of Americans have ever tried to gather and write down their family's health history.

Here are some tips to help you being to gather information:

I’ve highlighted several other methods of creating histories in the past, some of which you may prefer. A few excerpts (and links) from these essays.First, I’ll show you how I create and maintain histories for my Dad (who passed away last year) and myself. This was featured in an essay called A History Lesson.

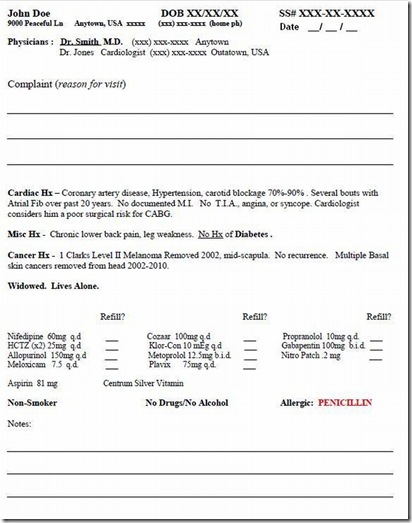

Today I’m going to impart a little secret that will ingratiate yourself with your doctor and not only improve the care you receive, but also reduce the amount of time you spend in the exam room. When you go to your doctor, have a brief written history printed out for him or her.

I’ve created a sample based on the one I used for my Dad (the details have been changed). It gets updated, and goes with him, for every doctor’s visit.

And his doctors love it.

While every history will be different, there are a few `rules’.

- First, keep it to 1 page. Even if the patient has an `extensive history’. If your doctor can’t scan this history, and glean the highlights, in 60 seconds or less . . . it isn’t of much use.

- Second, paint with broad strokes. Don’t get bogged down in details. Lab tests and such should already be in your chart.

- Third, always fill in a reason for your visit. Keep it short, your doctor will probably have 10 to 15 minutes to spend with you. Have your questions and concerns down in writing before you get there.

- Fourth, list all Meds (Rx and otherwise) and indicate which ones you need a refill on. If you have a question about a med, put a `?’ next to it. And if you have any drug allergies, Highlight them.

- Fifth, Make two copies! One for your doctor to keep, and one for you. As you talk to your doctor, make notes on the bottom (bring a pen) of your copy.

Once you create the basic template (using any word processor), it becomes a 5 minute job to update and print two copies out for a doctor’s visit.

The history above is great for scheduled doctor’s visits, but you also should have a readily available (preferably carried in your wallet or purse), EMERGENCY Medical History Card.

I addressed that issue in a blog called Those Who Forget Their History . . . . A few excerpts (but follow the link to read the whole thing):

Since you can’t always know, in advance, when you might need medical care it is important to carry with you some kind of medical history at all times. It can tell doctors important information about your history, medications, and allergies when you can’t.

Many hospitals and pharmacies provide – either free, or for a very nominal sum – folding wallet medical history forms with a plastic sleeve to protect them. Alternatively, there are templates available online.

I’ve scanned the one offered by one of our local hospitals below. It is rudimentary, but covers the basics.

And a couple of other items, while not exactly a medical history, may merit discussion in your family as it has recently in mine.

- First, all adults should consider having a Living Will that specifies what types of medical treatment you desire should you become incapacitated.

- You may also wish to consider assigning someone as your Health Care Proxy, who can make decisions regarding your treatment should you be unable to do so for yourself.

- Elderly family members with chronic health problems, or those with terminal illnesses, may even desire a home DNR (Do Not Resuscitate) Order.

Verbal instructions by family members – even if the patient is in the last stages of an incurable illness – are likely to be ignored by emergency personnel.

In Florida, the form must be printed on yellow paper. Different states have different requirements. You should check with your doctor, or the local department of health to determine what the law is in your location.

My father, who’s health declined greatly in his 86th year, requested a DNR in early 2011. That – along with securing home hospice care (see His Bags Are Packed, He’s Ready To Go) – allowed him to die peacefully at home in his own bed.

Admittedly, not the cheeriest topic of conversation in the world, but for a lot of people, this is an important issue to address.

A few minutes spent this holiday weekend putting together medical histories could spare you and your family a great deal of anguish down the road.