# 7989

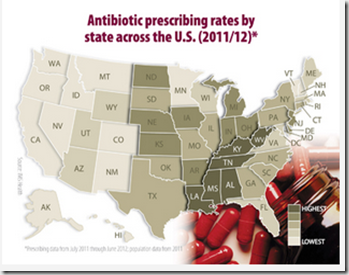

As the graphic above shows, there is considerable geographic disparity in the amount of antibiotics being prescribed across this country, with doctors some parts of the country being much quicker write ABx scripts than doctors in other regions.

In an attempt to bring some sensible level of standardization to the prescribing these drugs – and in so doing, hopefully reduce the creation and spread of antibiotic resistant bacteria - the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and the CDC have produced a new set of guidelines for doctors to encourage the judicious use of antibiotics when treating children with suspected bacterial infections.

First, some excerpts from the CDC’s press release, and then a link to the article in the journal Pediatrics.

New guidance limits antibiotics for common infections in children

Get Smart About Antibiotics Week 2013 calls for responsible antibiotic prescribing

Every year as many as 10 million U.S. children risk side effects from antibiotic prescriptions that are unlikely to help their upper respiratory conditions. Many of these infections are caused by viruses, which are not helped by antibiotics.

This overuse of antibiotics, a significant factor fueling antibiotic resistance, is the focus of a new report Principles of Judicious Antibiotic Prescribing for Bacterial Upper Respiratory Tract Infections in Pediatrics by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Released today during Get Smart About Antibiotics Week, the report amplifies recent AAP guidance and promotes responsible antibiotic prescribing for three common upper respiratory tract infections in children: ear infections, sinus infections, and sore throats.

Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria evolve and are able to outsmart antibiotics, making even common infections difficult to treat. According to a landmark CDC report from September 2013, each year more than two million Americans get infections that are resistant to antibiotics and 23,000 die as a result.

For Clinicians:

3 Principles of Responsible Antibiotic Use

- Determine the likelihood of a bacterial infection: Antibiotics should not be used for viral diagnoses when a concurrent bacterial infection has been reasonably excluded.

- Weigh benefits versus harms of antibiotics: Symptom reduction and prevention of complications and secondary cases should be weighed against the risk for side effects and resistance, as well as cost.

- Implement accurate prescribing strategies: Select an appropriate antibiotic at the appropriate dose for the shortest duration required.

“Our medicine cabinet is nearly empty of antibiotics to treat some infections,” said CDC Director Tom Frieden, M.D., M.P.H. “If doctors prescribe antibiotics carefully and patients take them as prescribed we can preserve these lifesaving drugs and avoid entering a post-antibiotic era.”

By providing detailed clinical criteria to help physicians distinguish between viral and bacterial upper respiratory tract infections, the recommendations provide guidance for physicians that will improve care for children. At the same time, it will help limit antibiotic prescriptions, giving bacteria fewer chances to become resistant and lowering children’s risk of side effects.

The entire 11 page PDF is available online from the American Academy of Pediatrics (see link below). The authors describe this guidance:

This clinical report focuses on antibiotic prescribing for key pediatric URIs that, in certain instances, may benefit from antibiotic therapy: AOM, acute bacterial sinusitis, and pharyngitis. The specific recommendations are applicable to healthy children who do not have underlying medical conditions (eg, immunosuppression) placing themat increased risk of developing serious complications. The purpose of this report is to provide practitioners specific context using the most current recommendations and guidelines while applying 3 principles of judicious antibiotic use: (1) determination of the likelihood of a bacterial infection, (2) weighing the benefits and harms of antibiotics, and (3) implementing judicious prescribing strategies.

Follow the link to read and download the entire report:

Adam L. Hersh, Mary Anne Jackson, Lauri A. Hicks and the COMMITTEE ON INFECTIOUS DISEASES

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-3260 ; originally published online November 18, 2013; Pediatrics

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/early/2013/11/12/peds.2013-3260

For more on this week’s focus on better stewardship of our antibiotic arsenal, you may wish to visit these recent blogs:

Surviving Winter’s Ills Without Abusing Antibiotics

The Lancet: Antibiotic Resistance - The Need For Global Solutions

ECDC: Antibiotic Resistance In the EU – 2012