Chinese Pangolin, an endangered delicacy – Credit Wikpedia

# 8808

Last week Chinese scientists announced the discovery of a `SARS-like’ coronavirus in bats examined in China’s Southern Yunnan province, one they said was a `relative’ of the 2003 epidemic strain, and one that could infect humans (see People’s Daily Online Chinese scientists find new SAR-like coronavirus).

Given the large number of viruses known to be carried by bats – including a number of coronaviruses – this discovery seems more inevitable than surprising.

But it does remind us that many wild (and sometimes, domesticated) animals can harbor dangerous pathogens that are but one fortuitous human-animal contact away from `spilling over’ into the human population. According to the CDC:

Approximately 75% of recently emerging infectious diseases affecting humans are diseases of animal origin; approximately 60% of all human pathogens are zoonotic.

The 2002-2003 SARS epidemic, which infected 8,000 people and killed nearly 800, was believed sparked by the slaughter and consumption of exotic animals at `wild flavor’ restaurants in Guangdong Province China. We aren’t talking subsistence `bushmeat’ here, but exotic and expensive dishes prepared for the wealthy, including: pangolin, cobra, tiger, bear, monkeys, dogs, cats, and palm civets.

Although the exact sequence of events will never be known, it is believed that a SARS infected exotic animal – likely a palm civet (which likely acquired the virus from a bat – the suspected natural reservoir for the virus) – was prepared and served at one of these `wild flavor’ restaurants, and in so doing infected either a patron (or more likely), one of the staff, sparking the epidemic.

Many of these animals are also on the endangered list. They are highly coveted by locals – not only for the culinary experience – but for their supposed `health benefits’ producing vigor, vitality, and increasing sexual prowess.

Ounce for ounce, many of the more exotic ingredients used in traditional Chinese medicine (including rhino horn, bear bile, tiger blood, or deer musk) are more valuable than gold, making theirs a lucrative trade.

Although China cracked down on `wild flavor’ markets and restaurants after the SARS epidemic, enforcement has been lax, and the trade continues, albeit not quite as openly as before. Last April China announced another crackdown, including stiff jail sentences for consumers.

China to jail eaters of rare wild animals

English.news.cn | 2014-04-24 21:10:20 | Editor: Yang Yi

BEIJING, April 24 (Xinhua) -- China's top legislature on Thursday passed an interpretation of the Criminal Law which will put eaters of rare wild animals in jail.

The Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPC), China's top legislature, adopted the interpretation through a vote at its bimonthly session which closed here on Thursday.

Currently, 420 species of wild animals are considered rare or endangered by the Chinese government. They include giant pandas, golden monkeys, Asian black bears and pangolins.

According to the legal document, anyone who eats the animals in this list or buys them for other purposes will be considered to be breaking the Criminal Law and will face a jail term from below five years to more than 10 years, depending on the degree of offending.

Having one of the world's richest wildlife resources, China is home to around 6,500 vertebrate species, about 10 percent of the world's total. More than 470 terrestrial vertebrates are indigenous to China, including giant pandas, golden monkeys, South China tigers and Chinese alligators.

However, the survival of wildlife in the country faces serious challenges from illegal hunting, consumption of wild animal products and a worsening environment.

(Continue . . . )

Despite this new crackdown, according to an illuminating report today from AFP, the trade in exotic (and often endangered) animals in China continues with vigor.

Clampdown on China's animal eaters fails to bite

CONGHUA, China: Porcupines in cages, endangered tortoises in buckets and snakes in cloth bags -- rare wildlife is on open sale at a Chinese market, despite courts being ordered to jail those who eat endangered species.

The diners of southern China have long had a reputation for exotic tastes, with locals sometimes boasting they will "eat anything with four legs except a table".

China in April raised the maximum sentence for anyone caught selling or consuming endangered species to 10 years in prison, but lax enforcement is still evident in the province of Guangdong.

"I can sell the meat for 500 yuan ($80) per half kilo," a pangolin vendor at the Xingfu -- "happy and rich" -- wholesale market in Conghua told AFP. "If you want a living one it will be more than 1,000 yuan."

Although the risks to public health are not mentioned in this AFP article, they exist today every bit as much today as they did more than a decade ago when SARS emerged. And not just from `exotic or wild’ animals.

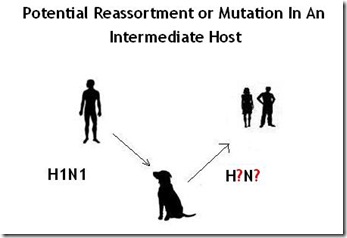

In late 2012, in China: Avian-Origin Canine H3N2 Prevalence In Farmed Dogs, we saw a study that found more than 12% of farmed dogs tested in Guangdong province carried a strain of canine H3N2 similar to that seen in Korea. The authors cautioned:

As H3N2 outbreaks among dogs continue in the Guangdong province (located very close to Hong Kong), the areas where is densely populated and with frequent animal trade, there is a continued risk for pets H3N2 CIV infections and for mutations or genetic reassortment leading to new virus strains with increased transmissibility among dogs.

Further in-depth study is required as the H3N2 CIV has been established in different dog populations and posed potential threat to public health.

Elsewhere in the world, the current Ebola outbreak in western Africa is likely to have emerged through the killing, preparation, and/or consumption of infected bushmeat. As in China, there have been attempts by local governments and public health organizations to curtail their trade, but with little success (see Liberia: MOH Press Conference On Ebola Outbreak).

A similar concern has been raised in the Middle East, where the consumption of camel products (meat, milk, etc.) has been suggested as being a possible route of MERS-CoV infection in humans (see WHO Update On MERS-CoV Transmission Risks From Animals To Humans).

And just last Friday, Reuters reported on an illegal slaughtering operation with tragic results (see Five people hospitalized for suspected anthrax infection in Hungary).

Last month, in `Carrion’ Luggage & Other Ways To Import Exotic Diseases, we looked at the extensive international smuggling of bushmeat, and exotic animals, which are also potential routes of zoonotic disease introduction and spread.

Beyond SARS, and Ebola, and MERS, a few other zoonotic diseases of concern include Hendra, Nipah, Monkeypox, a variety of avian influenzas, other coronaviruses, various hemorrhagic fevers, many variations of SIV (Simian immunodeficiency virus), and of course . . . Virus X.

The one we don’t know about. Yet.