# 4678

In terms of total numbers of reported human H5N1 infections, Egypt ranks 3rd in the world with 109 cases, led by Indonesia (n=165) and Vietnam (n=119).

With a current CFR (case fatality ratio) of 31%, Egypt’s fatality rates substantially lower than that seen in Vietnam (50%) and Indonesia (82%).

While there may be some subtle differences in the virus circulating in Egypt, much of the credit for this lower fatality rate has been given to earlier hospitalization and treatment.

This month’s CDC’s EID journal has an in depth look at the epidemiology of H5N1 transmission in Egypt through March of 2009. This covers the first 63 human cases.

Since that time, there have been more than 40 additional cases, so some of the statistics have changed a bit.

First the link and abstract, then a little discussion.

Volume 16, Number 7–July 2010

Research

Zoonotic Transmission of Avian Influenza Virus (H5N1), Egypt, 2006–2009

Amr Kandeel, Serge Manoncourt, Eman Abd el Kareem, Abdel-Nasser Mohamed Ahmed, Samir El-Refaie, Hala Essmat, Jeffrey Tjaden, Cecilia C. de Mattos, Kenneth C. Earhart, Anthony A. Marfin, and Nasr El-Sayed

Abstract

During March 2006–March 2009, a total of 6,355 suspected cases of avian influenza (H5N1) were reported to the Ministry of Health in Egypt. Sixty-three (1%) patients had confirmed infections; 24 (38%) died.

Risk factors for death included female sex, age >15 years, and receiving the first dose of oseltamivir >2 days after illness onset. All but 2 case-patients reported exposure to domestic poultry probably infected with avian influenza virus (H5N1). No cases of human-to-human transmission were found.

Greatest risks for infection and death were reported among women >15 years of age, who accounted for 38% of infections and 83% of deaths. The lower case-fatality rate in Egypt could be caused by a less virulent virus clade. However, the lower mortality rate seems to be caused by the large number of infected children who were identified early, received prompt treatment, and had less severe clinical disease.

As the title of this report indicates, the transmission of the virus in Egypt thus far has been solely attributed to infected poultry.

No H2H (Human-to-Human) transmission has been identified.

The virus has become endemic in Egyptian poultry since its arrival in 2006. Many households raise chickens for food, and as an income source, and tending the birds is usually a job for young females in the family.

A demographic breakdown of victims shows that females outnumber males, and 97% of victims are under the age of 50.

Most telling is that 87% of the fatal cases were among females.

(Click to enlarge)

The `seasonality’ of infection is clearly shown in the chart below, with the winter and spring seeing the greatest number of cases.

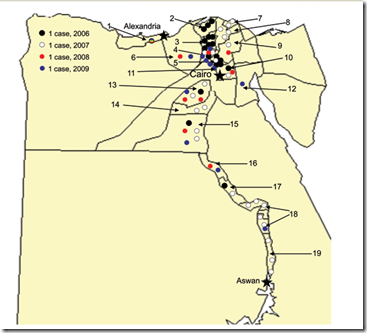

While this distribution map shows that the bulk of the infections have occurred in northern Egypt.

The early administration of Tamiflu has been credited with better outcomes in Egyptian cases, and this report provides some compelling observational data as to its efficacy.

Of 58 patients for whom complete data for oseltamivir was available, 25 (43%) received their first dose <48 hours after illness onset; all but 1 survived.

Median duration of treatment was 8 days (range 1–37 days). The first dose of oseltamivir was more likely to be delayed for adults. Twenty (80%) of 25 adults had a delay before receiving oseltamivir compared with 13 (39%) of 33 children (p = 0.005).

Conversely, late hospitalization and the administration of Tamiflu was associated with greater mortality.

Eighteen (90%) of 20 adults whose first oseltamivir dose was delayed died compared with 1 (20%) of 5 adults whose first oseltamivir dose was not delayed (p = 0.005). None of 20 children who received oseltamivir <48 hours of illness onset died compared with 1 (8%) of 13 children whose first dose was delayed.

(Click to enlarge)

It should be noted that early hospitalization provides other benefits besides Tamiflu (i.e. antibiotics, rehydration, antipyretics, nursing care, etc), and so some of these better outcomes may be due to factors other than just the early administration of antivirals.

Even with the faster, more modern medical care available in Egypt, a CFR of over 30% for influenza is still appalling.

The great pandemic of 1918 was estimated to have a CFR of between 2.5% and 5.0%.

Since the cut off date of this report (Mar 2009), the percentage of younger victims has gone up, while the CFR has decreased from 38% down to about 31%.

And once again we appear to be in the summer lull of human infections, with no new reports since April.

This is an excellent overview of the progression of H5N1 infection in Egypt, and well worth reading in its entirety.