Credit CDC PHIL

# 7005

China has often been referred to as the `the cradle of influenza’, based primarily on 20th century history, as the 1957 and 1968 pandemics both are believed to have originated there. Additionally, the highly pathogenic `Asian’ version of H5N1 emerged from China in the mid 1990s.

Asia is seemingly an ideal breeding ground and launching pad for novel flus, as millions of humans and farm animals live in relatively close contact, which provides abundant opportunities for human-avian or human-swine flu reassortments.

Shift, or reassortment, happens when two different influenza viruses co-infect the same host and swap genetic material creating a new, hybrid virus – Credit AFD

But these conditions are not necessarily unique to China or Southeast Asia, and given the limits of global animal surveillance, it is important to concentrate resources in those places in the world where the next influenza pandemic virus is most likely to first emerge.

Yesterday, the CDC’s EID Journal published a research article that identifies 6 key geographic regions, called:

Research

Predicting Hotspots for Influenza Virus Reassortment

Trevon L. Fuller , Marius Gilbert, Vincent Martin, Julien Cappelle, Parviez Hosseini, Kevin Y. Njabo, Soad Abdel Aziz, Xiangming Xiao, Peter Daszak, and Thomas B. Smith

Abstract

The 1957 and 1968 influenza pandemics, each of which killed ≈1 million persons, arose through reassortment events. Influenza virus in humans and domestic animals could reassort and cause another pandemic.

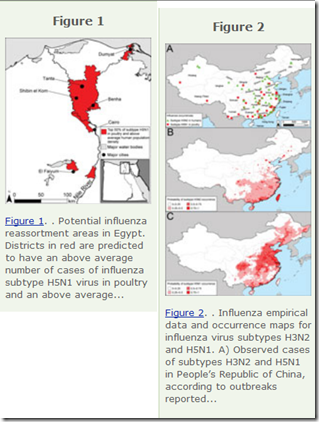

To identify geographic areas where agricultural production systems are conducive to reassortment, we fitted multivariate regression models to surveillance data on influenza A virus subtype H5N1 among poultry in China and Egypt and subtype H3N2 among humans. We then applied the models across Asia and Egypt to predict where subtype H3N2 from humans and subtype H5N1 from birds overlap; this overlap serves as a proxy for co-infection and in vivo reassortment.

For Asia, we refined the prioritization by identifying areas that also have high swine density.

Potential geographic foci of reassortment include the northern plains of India, coastal and central provinces of China, the western Korean Peninsula and southwestern Japan in Asia, and the Nile Delta in Egypt.

This research was led by UCLA’s Center for Tropical Research, and a news release published yesterday highlights some of the difficulties of data acquisition from these regions.

Predicting hotspots for future flu outbreaks

By Alison Hewitt March 13, 2013

(EXCERPT)

The research focused on two flu strains that studies in mice have shown can combine with lethal results: the seasonal H3N2 human flu, and the H5N1 strain of bird flu that has occasionally crossed over into humans. Currently, H5N1 has a 60 percent mortality rate in humans but is not known to spread between humans frequently.

While the World Health Organization has identified six countries as hosts to ongoing, widespread bird flu infections in poultry in 2011 — China, Egypt, India, Vietnam, Indonesia and Bangladesh — the UCLA researchers and their colleagues had limited data to work with. Not all flu outbreaks, whether bird or human, are tracked. The scientists had to identify indicators of flu outbreaks, such as dense poultry populations, or rain and temperatures that encourage flu transmission.

"For each type of flu, we identified variables that were predictive of the various virus strains," Fuller said. "We wanted a map of predictions continuously across the whole country, including locations where we didn't have data on flu outbreaks."

Although the researchers had bird flu data for parts of both China and Egypt, other countries, such as Indonesia, don't have full reporting systems in place. Even in China and Egypt, accurate reporting is hampered by farmers who may conceal flu outbreaks in order to sell their livestock.

It is worth noting that the last pandemic reassortment originated in the Americas, and no one is quite sure where the devastating 1918 `Spanish’ flu first emerged.

While it makes sense to focus surveillance on the most likely region to spawn the next pandemic, one can’t dismiss the possibility of a dark horse entry coming out of left field.

Returning to the EID Journal report, the authors conclude by writing:

The potential for reassortment between human and avian influenza viruses underscores the value of a One Health approach that recognizes that emerging diseases arise at the convergence of the human and animal domains (29,40).

Although our analysis focused on the influenza virus, our modeling framework can be generalized to characterize other potential emerging infectious diseases at the human–animal interface.

![Reassortant pig[6] Reassortant pig[6]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgppTv7U9dZhh_wVqRdXedk6ElNkgm4B-LSTvmtqAyWYERTknTtfF1FxNLm3GMOlYI6MohfGUmrDBDKSXbAQ22-pDR7LRpCGc9u7IuTcnNUTQVm2hSh0YiTbRFxY5zVhkKqLbG_Ng/?imgmax=800)