Credit CDC PHIL

# 6976

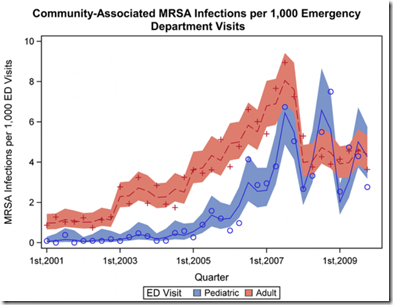

Just shy of two years ago, in MRSA: It’s Got Seasonality, we looked at a PLoS One study that found a significant spike in CA-MRSA infections reported by Rhode Island Emergency rooms during the 3rd & 4th quarters of the year.

Seasonality of MRSA Infections

Mermel LA, Machan JT, Parenteau S (2011) Seasonality of MRSA Infections. PLoS ONE 6(3): e17925. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017925

The authors reported that pediatric patients saw roughly 1.85 times as many community-associated CA-MRSA infections and 2.94 times as many hospital-associated HA-MRSA infections in the second two quarters of the year as opposed to the first two quarters.

While a similar pattern was observed for adults, it was less pronounced, with 1.14 times as many CA-MRSA infections in the 3rd & 4th quarters, but no detectable increase in adult HA-MRSA infections.

The authors suggested that factors such as excessive hydration of the skin (sweating), summer insect bites, and warm, humid environments conducive to bacterial survival and spread may partially account for the rise, but summer conditions alone cannot not account for the increases.

Temperatures in the 2nd quarter of the year in Rhode Island are normally much higher than during the 4th quarter.

Fast forward a couple of years, and a new study in the American Journal of Epidemiology finds a similar - but not quite identical – pattern across the United States between 2005 and 2009.

The Changing Epidemiology of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the United States: A National Observational Study

Eili Y. Klein, Lova Sun, David L. Smith and Ramanan Laxminarayan*

While the abstract is free, the complete study is behind a subscription/pay wall. Luckily, the following press release from Johns Hopkins Medicine gives us a pretty good overview.

Strains of antibiotic-resistant 'Staph' bacteria show seasonal preference; children at higher risk in summer

Strains of potentially deadly, antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteria show seasonal infection preferences, putting children at greater risk in summer and seniors at greater risk in winter, according to results of a new nationwide study led by a Johns Hopkins researcher.

It's unclear why these seasonal and age preferences for infection with methicillin-resistant Staph aureus (MRSA) occur, says Eili Klein, Ph.D., lead author on the study and a researcher at the Johns Hopkins Center for Advanced Modeling in the Social, Behavioral and Health Sciences.

But he says that increased use of antibiotics in the winter may be one of the reasons. The winter strain that infects seniors at a greater rate is generally acquired in the hospital and resistant to more antibiotics. On the other hand, the summer strain of MRSA, which is seen with growing frequency in children, is largely a community-transmitted strain that is resistant to fewer antibiotics.

"Overprescribing antibiotics is not harmless," Klein notes. "Inappropriate use of these drugs to treat influenza and other respiratory infections is driving resistance throughout the community, increasing the probability that children will contract untreatable infections."

In fact, the study found that while MRSA strains exhibit a seasonal pattern, overall MRSA infections have not decreased over the last five years, despite efforts to control their spread.

A report on the study, which used sophisticated statistical models to analyze national data for 2005-2009, appears today in the online issue of the American Journal of Epidemiology.

As the researchers report, hospitalizations from infections tied to MRSA doubled in the United States between 1999 and 2005. The ballooning infection numbers were propelled by MRSA acquired in community settings, not hospital or other health care settings, as had been the case prior to 1999.

Specifically, the study found that a strain of MRSA typically seen in community settings is more likely to cause infection during the summer months, peaking around July/August. The authors' data analysis showed children were most at risk of becoming infected with this strain, typically from a skin or soft tissue wound or ailment.

In fact, in examining data for one year — 2008 — the research team found that 74 percent of those under the age of 20 who developed an infection with MRSA had a community-associated MRSA infection.

Meanwhile, the health care-associated MRSA strain, which is typically seen in hospitals, nursing homes and other health care settings, was found to be most prevalent in the winter months, peaking in February/March. Patients aged 65 or older are more likely to acquire a MRSA infection from this strain.

"Our analysis ... shows significant seasonality of MRSA infections and the rate at which they affect different age groups," write the authors of the report titled "The changing epidemiology of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in the United States: A national observational study."

Klein said additional research on seasonal patterns of MRSA infections and drug resistance may help with developing new treatment guidelines, prescription practices and infection control programs.

Unlike with the smaller Rhode Island study, these researchers found an increase in HA-MRSA among adults (particularly over the age of 65) that peaked during the 1st quarter. A trend, the authors suggest, that may be linked to the increased use of antibiotics during the winter.

From the Abstract, the authors sum up:

We observed significant differences in infection type by age, with HA-MRSA–related hospitalizations being more common in older individuals. We also noted significant seasonality in incidence, particularly in children, with CA-MRSA peaking in the late summer and HA-MRSA peaking in the winter, which may be caused by seasonal shifts in antibiotic prescribing patterns.