MRSA - Photo Credit CDC

# 9804

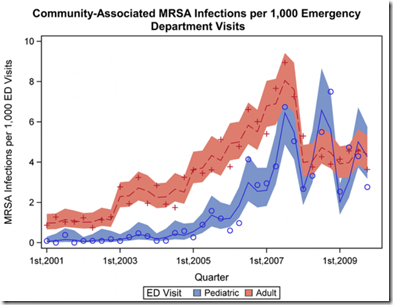

From the Open Access journal mBio this morning, a report that suggests that MRSA can hang around a household, bounce repeatedly between family members, and evolve into a unique `family’ strain, over a period of several years.

Previously we’ve looked at MRSA colonization, where the CDC quantified colonization by stating:

While 25% to 30% of people are colonized* in the nose with staph, less than 2% are colonized with MRSA (Gorwitz RJ et al. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2008:197:1226-34.).

*Colonized:

When a person carries the organism/bacteria but shows no clinical signs or symptoms of infection. For Staph aureus the most common body site colonized is the nose.

However, in Firefighters & Paramedics At Greater Risk Of MRSA and Firefighters & MRSA Revisited we looked at research showing a 10x’s greater incidence of MRSA colonization (20%) among a sampling of firefighters tested in Washington State.

As we learn from an American Society of Microbiology press release today (see MRSA can linger in homes, spreading among its inhabitants), a 2012 study found up to 50% of family contacts in households with one SSTI (Skin or soft Tissue Infection) with MRSA were colonized with the resistant bacteria.

They describe the findings of today’s study as:

Households can serve as a reservoir for transmitting methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), according to a study published this week in mBio®, the online open-access journal of the American Society for Microbiology. Once the bacteria enters a home, it can linger for years, spreading from person to person and evolving genetically to become unique to that household.

<SNIP>

he researchers found that isolates within households clustered into closely related groups, suggesting a single common USA300 ancestral strain was introduced to and transmitted within each household. Researchers also determined from a technique called Bayesian evolutionary reconstruction that USA300 MRSA persisted within households from 2.3 to 8.3 years before their samples were collected, and that in the course of a year, USA300 strains had a 1 in a million chance of having a random genetic change, estimating the speed of evolution in these strains. Researchers also found evidence that USA300 clones, when persisting in households, continued to acquire extraneous DNA.

"We found that USA300 MRSA strains within households were more similar to each other than those from different households," said senior study author Michael Z. David, MD, PhD, an assistant professor of edicine at the University of Chicago. Although MRSA is introduced into households rarely, he said, once it gets in, "it can hang out there for years, ping-ponging around from person to person. Our findings strongly suggest that unique USA300 MRSA isolates are transmitted within households that contain an individual with a skin infection."

A link, and the abstract to the entire mBio report can be accessed below:

Md Tauqeer Alama, Timothy D. Reada,b, Robert A. Petit IIIa, Susan Boyle-Vavrac, Loren G. Millerd, Samantha J. Eellsd, Robert S. Daumc, Michael Z. Davidc,e

ABSTRACT

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) USA300 is a successful S. aureus clone in the United States and a common cause of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs). We performed whole-genome sequencing (WGS) of 146 USA300 MRSA isolates from SSTIs and colonization cultures obtained from an investigation conducted from 2008 to 2010 in Chicago and Los Angeles households that included an index case with an S. aureus SSTI.

Identifying unique single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and analyzing whole-genome phylogeny, we characterized isolates to understand transmission dynamics, genetic relatedness, and microevolution of USA300 MRSA within the households. We also compared the 146 USA300 MRSA isolates from our study with the previously published genome sequences of the USA300 MRSA isolates from San Diego (n = 35) and New York City (n = 277). We found little genetic variation within the USA300 MRSA household isolates from Los Angeles (mean number of SNPs ± standard deviation, 17.6 ± 35; π nucleotide diversity, 3.1 × 10−5) or from Chicago (mean number of SNPs ± standard deviation, 12 ± 19; π nucleotide diversity, 3.1 × 10−5).

The isolates within a household clustered into closely related monophyletic groups, suggesting the introduction into and transmission within each household of a single common USA300 ancestral strain. From a Bayesian evolutionary reconstruction, we inferred that USA300 persisted within households for 2.33 to 8.35 years prior to sampling. We also noted that fluoroquinolone-resistant USA300 clones emerged around 1995 and were more widespread in Los Angeles and New York City than in Chicago. Our findings strongly suggest that unique USA300 MRSA isolates are transmitted within households that contain an individual with an SSTI. Decolonization of household members may be a critical component of prevention programs to control USA300 MRSA spread in the United States.

IMPORTANCE USA300, a virulent and easily transmissible strain of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), is the predominant community-associated MRSA clone in the United States. It most commonly causes skin infections but also causes necrotizing pneumonia and endocarditis. Strategies to limit the spread of MRSA in the community can only be effective if we understand the most common sources of transmission and the microevolutionary processes that provide a fitness advantage to MRSA.

We performed a whole-genome sequence comparison of 146 USA300 MRSA isolates from Chicago and Los Angeles. We show that households represent a frequent site of transmission and a long-term reservoir of USA300 strains; individuals within households transmit the same USA300 strain among themselves. Our study also reveals that a large proportion of the USA300 isolates sequenced are resistant to fluoroquinolone antibiotics. The significance of this study is that if households serve as long-term reservoirs of USA300, household MRSA eradication programs may result in a uniquely effective control method.