# 9420

In addition to providing the usual scourges of malaria, dengue, seasonal influenza, antibiotic resistant bacteria and pneumonia, 2014 has provided us with a number of new, or sometimes simply transplanted, disease threats around the world.

A reminder that in our highly mobile and interconnected world, a disease threat anywhere can easily become a disease threat everywhere.

The tone for the new year was set during the opening days of January when we saw North America’s first imported case of H5N1 ex-China (see Alberta Canada Reports Fatal (Imported) H5N1 Infection). During that same week, Hong Kong was dealing with imported cases of H9N2 (link) and H7N9 (link) while Taiwan was dealing with an imported H7N9 infection (see A Bit More On Taiwan’s Imported H7N9 Case).

Although these cases were contained they served to remind us how easily a novel flu virus can hop a plane and travel from one country to the next.

The first cases (2 confirmed, 4 probable, 20 suspected) of Chikungunya on the French part of St. Martins were reported in early December of last year, likely imported by a viremic tourist, but by early January it was apparent that the virus was thriving, and spreading across the Caribbean courtesy of a highly competent local mosquito vector.

The ECDC reported as of 9 January 2014:

- 201 probable or confirmed cases in Saint Martin (FR);

- 2 confirmed cases in Saint Martin (NL);

- 48 probable or confirmed cases in Martinique;

- 25 probable or confirmed cases in Saint Barthélemy;

- 10 probable or confirmed cases including one imported case from Saint Martin in Guadeloupe;

- 1 confirmed case imported from Martinique in French Guiana.

Within weeks there would be thousands of cases, and within months hundreds of thousands. From these humble beginnings, in less than a year, the latest PAHO surveillance report (December 5th, 2014) puts the number who have been infected in the Americas now at just under 1 million people – although that is likely an undercount.

Of some solace, while painful and sometimes debilitating, Chikungunya has a fairly low mortality rate. Still hundreds have died, and thousands have suffered long-term disability due to the virus.

Although there have only been 11 locally acquired cases in the continental United States (all in Florida), this year more than 1,900 visitors have tested positive for the virus, increasing the odds that CHKV will eventually take up residence in North America.

We’ve seen similar expansion of Dengue this year, with major new outbreaks in China and Japan.

While we were watching the second wave of H7N9 accelerate in China, on January 17th we learned of the first outbreak of a new subtype of avian flu; H5N8 (see Media Reporting Korean Poultry Outbreak Due To H5N8) – which over the next several months would result in the culling of more than 13 million birds.

Currently only a threat to poultry, this virus has – over the first 11 months – spread as far east as Japan and as far west as the UK, likely carried by migratory birds. Where it shows up next is anyone’s guess.

H5N8 Branching Out To Europe & Japan

Adding complexity to last winter’s bird flu season, we also saw three human infections with a new H10N8 virus (see Jiangxi Province Reports Second H10N8 Infection), and later in the spring, with a never-before-seen HPAI H5N6 virus (see Sichuan China: 1st Known Human Infection With H5N6 Avian Flu).

Both are wild cards for the upcoming winter season, but will have to be watched carefully for further spread. H5N6, in particular, has been widely reported in poultry across both China and Vietnam in recent months.

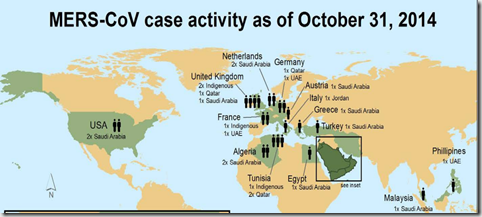

And while H7N9 set worrisome new records for human infections during its second wave (n=322 cases vs 134 cases) last winter and spring, on the Arabian Peninsula MERS was also setting new records, and expanding its geographic range as well.

The United States saw two imported cases last May, but it wasn’t alone, as more than a dozen nations have seen imported cases from the Middle East. With a distinct seasonal pattern, we can probably expect another surge in MERS cases after the new year.

Credit BCCDC

And while bird flu and MERS kept us busy during the first half of 2014, since the summer the first regional epidemic of Ebola – and in an area (West Africa) where it had never previously sparked an outbreak – became the big infectious disease threat of the year.

With at least 17,000 infected (estimates range up to 2.5x’s official counts) and more than 6,000 dead, this Ebola outbreak continues to re-write the rules of how Ebola is expected to behave.

Credit WHO Roadmap Dec 3rd.

While the effect of this epidemic on nations in western Africa has been nothing less than devastating, so far the impact from exported cases to the United States and Europe has been fairly limited. It has, however, necessitated the creation of an extensive and expensive surveillance and reporting system here in the U.S., and around the globe.

A far lesser threat, here is the United States we saw an outbreak of a rarely-seen non-polio enterovirus (EV-D68) starting last August -first reported in Kansas City - but quickly spreading across the nation. While most only saw mild illness, at the same time we saw a few dozen children experience a rare form of paralysis thought to be linked to the virus (see CIDRAP: Likely That Polio-like Illness & EV-D68 Are Linked).

There were others, of course. One off’s like the imported case of Lassa Fever in Minneapolis, MN and an imported case of CCHF (ex-Bulgaria) to the UK.

Like embers drifting from a distant fire, most of the time these disease introductions burn out without harm, but they nonetheless harbor some potential to ignite where ever they land.

The reality of life in this second decade of this new century is that disease threats that once were local, can now spread globally in a matter of hours or days, thanks to our highly mobile society.

And as our population and mobility have grown, so have the number of emerging infectious disease threats. Something that was foretold two decades ago by anthropologist and researcher George Armelagos of Emory University, which I described in considerable detail in The Third Epidemiological Transition.

Earlier this year, we looked at an assessment by the Director Of National Intelligence who includes emerging infectious diseases and Influenza Pandemic As A National Security Threat.

From that report:

Worldwide Threats Assessment – published January 29th, 2014,

(Excerpt)

Health security threats arise unpredictably from at least five sources:

- the emergence and spread of new or reemerging microbes;

- the globalization of travel and the food supply;

- the rise of drug-resistant pathogens;

- the acceleration of biological science capabilities and the risk that these capabilities might cause inadvertent or intentional release of pathogens; and

- adversaries’ acquisition, development, and use of weaponized agents.

Infectious diseases, whether naturally caused, intentionally produced, or accidentally released, are still among the foremost health security threats. A more crowded and interconnected world is increasing the opportunities for human, animal, or zoonotic diseases to emerge and spread globally. Antibiotic drug resistance is an increasing threat to global health security. Seventy percent of known bacteria have now acquired resistance to at least one antibiotic, threatening a return to the pre-antibiotic era.

While we’ve heard the warnings for years, 2014 seems to have accented the message; global health security is truly a national security issue.

The obvious hotspots to watch right now center around China, Africa and the Middle East, but the 2009 H1N1 pandemic and this year’s EV-D68 outbreak show that our own backyard can be a fertile viral proving ground as well.

The rise or emergence of disease threats like MERS-CoV, H5N1, Nipah, Hendra, Lyme Disease, Ebola, H7N9, H10N8, H5N8, H5N6, NDM-1, CRE, etc. doesn’t appear to be a temporary aberration – but rather an ongoing trend - and so we need to be thinking about our local and global response to these threats.

And while you and I may not be able to do much personally about the international health response, we can ensure our families, friends, and businesses are better prepared to deal with whatever comes down the pike next.

Some earlier blogs on pandemic preparedness you may find worth re-visiting include:

MMWR: Updated Preparedness and Response Framework for Influenza Pandemics

It’s Not Just Ebola

NPM14: Because Pandemics Happen

Pandemic Planning For Business

Because, if what’s past is prologue, then 2015 could prove to be an even more challenging year when it comes to the emergence and expansion of infectious disease threats around the world.