Covering Pandemic and Seasonal Flu, Emerging Infectious Diseases, public health, community & Individual preparedness. NOTE: All AFD blogs are written by a human - any mistakes are solely mine.

Saturday, April 30, 2016

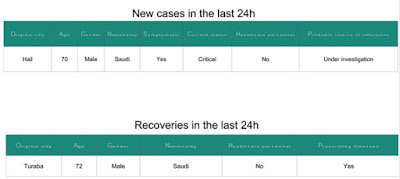

Saudi MOH Reports 1 MERS Case In Hail

#11,325

After going 6 days without a reported MERS infection, the Saudi MOH wraps up the month of April with their 15th notification - that of a 70 year-old male from Hail listed in critical condition.

The source of his exposure is still under investigation.

MMWR: Ongoing Zika Virus Transmission - Puerto Rico

|

| Credit MMWR |

#11,324

The news late yesterday afternoon of the first Zika death in a United States territory - while garnering a lot of press coverage - is far from unexpected.

Zika, like West Nile Virus and Chikungunya, has often been described as `rarely fatal', but last year West Nile Virus killed 119 Americans, and in 2015 PAHO reported 73 CHKV deaths in the Americas.

Both are likely under counts. And while rare in comparison to the hundreds of thousands of those mildly affected, fatal outcomes do occur.

This same (rare) pattern is expected with the Zika virus, particularly among the elderly, or in those with comordbidities or compromised immune systems.

While the greatest threat from the Zika virus remains to the developing fetus - for an unlucky few serious, and sometimes fatal complications such as Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) , Encephalitis, or Myelitis are possible.

This first death - which occurred back in February and was listed as due to severe thrombocytopenia - was announced in an Early Release MMWR published yesterday afternoon that updates the epidemiology and public health response to the ongoing Zika epidemic in Puerto Rico, from November 1, 2015–April 14, 2016.

During the first five and a half months, public health authorities screened 6,157 specimens, and validated 683 (11%) as laboratory confirmed Zika infections. The most frequently reported signs and symptoms were rash (74%) and myalgia (68%), with headache, fever, and arthralgia all reported in 63% of cases.

First, the MMWR summary, followed by the link to and some excerpts from the full report. Follow the link to read the report in its entirety.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?Zika virus transmission in Puerto Rico has been ongoing, with the first patient reporting symptom onset in November 2015. Zika virus infection is a cause of microcephaly and other severe birth defects. Zika virus infection has also been associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome.

What is added by this report?During November 1, 2015–April 14, 2016, a total of 6,157 specimens from suspected Zika virus–infected patients from Puerto Rico were evaluated and 683 (11%) had laboratory evidence of current or recent Zika virus infection. The public health response includes increased capacity to test for Zika virus, preventing infection in pregnant women, monitoring infected pregnant women and their fetus for adverse outcomes, controlling mosquitos, and assuring the safety of blood products.

What are the implications for public health practice?Residents of and travelers to Puerto Rico should continue to employ mosquito bite avoidance behaviors, take precautions to reduce the risk for sexual transmission, and seek medical care for any acute illness with rash or fever. Clinicians who suspect Zika virus disease in patients who reside in or have recently returned from areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission should report cases to public health officials.

Update: Ongoing Zika Virus Transmission — Puerto Rico, November 1, 2015–April 14, 2016

Early Release / April 29, 2016 / 65

Emilio Dirlikov, PhD1,2; Kyle R. Ryff, MPH1; Jomil Torres-Aponte, MS1; Dana L. Thomas, MD1,3; Janice Perez-Padilla, MPH4; Jorge Munoz-Jordan, PhD4; Elba V. Caraballo, PhD4; Myriam Garcia5,6; Marangely Olivero Segarra, MS5,6; Graciela Malave5,6; Regina M. Simeone, MPH7; Carrie K. Shapiro-Mendoza, PhD8; Lourdes Romero Reyes9; Francisco Alvarado-Ramy, MD10; Angela F. Harris, PhD11; Aidsa Rivera, MSN4; Chelsea G. Major, MPH4,12; Marrielle Mayshack1,12; Luisa I. Alvarado, MD13; Audrey Lenhart, PhD14; Miguel Valencia-Prado, MD15; Steve Waterman, MD4; Tyler M. Sharp, PhD4; Brenda Rivera-Garcia, DVM1 (View author affiliations)

View suggested citation

Zika virus is a flavivirus transmitted primarily by Aedes species mosquitoes, and symptoms of infection can include rash, fever, arthralgia, and conjunctivitis (1).* Zika virus infection during pregnancy is a cause of microcephaly and other severe brain defects (2). Infection has also been associated with Guillain-Barré syndrome (3). In December 2015, Puerto Rico became the first U.S. jurisdiction to report local transmission of Zika virus, with the index patient reporting symptom onset on November 23, 2015 (4).

(SNIP)

Discussion

Zika virus remains a public health challenge in Puerto Rico, and cases are expected to continue to occur throughout 2016. Building upon existing dengue and chikungunya virus surveillance systems, PRDH collaborated with CDC to establish a comprehensive surveillance system to characterize the incidence and epidemiology of Zika virus disease on the island. Expanded laboratory capacity and surveillance provided timely availability of data, allowing for continuous analysis and adapted public health response. Following CDC guidelines, both symptomatic and asymptomatic pregnant women are tested for evidence of Zika virus infection.

Information from the Zika Active Pregnancy Surveillance System will be used to raise awareness about the complications associated with Zika virus during pregnancy, encourage prevention through use of mosquito repellent and other methods, and inform health care providers of the additional care needed by women infected with Zika virus during pregnancy, as well as congenitally exposed fetuses and children. In addition, the prevalence of adverse fetal outcomes documented through this system can be compared with baseline rates as further evidence of associations between Zika virus infections and adverse outcomes, such as microcephaly (2).

The finding that women constitute the majority of cases might be attributable to targeted outreach and testing. The most common symptoms among Zika virus disease cases were rash, myalgia, headache, fever, and arthralgia, which are similar to the most common signs and symptoms reported elsewhere in the Americas (9). Although Zika virus–associated deaths are rare (10), the first identified death in Puerto Rico highlights the possibility of severe cases, as well as the need for continued outreach to raise health care providers’ awareness of complications that might lead to severe disease or death. To ensure continued blood safety, blood collection resumed with a donor screening program for Zika virus infection, and all units screened positive are removed.

Residents of and travelers to Puerto Rico should continue to employ mosquito bite avoidance behaviors, including using mosquito repellents, wearing long-sleeved shirts and pants, and ensuring homes are properly enclosed (e.g., screening windows and doors, closing windows, and using air conditioning) to avoid bites while indoors.††† To reduce the risk for sexual transmission, especially to pregnant women, precautions should include consistent and proper use of condoms or abstinence (5). Such measures can also help avoid unintended pregnancies and minimize risk for fetal Zika virus infection (6). Clinicians who suspect Zika virus disease in patients who reside in or have recently returned from areas with ongoing Zika virus transmission should report cases to public health officials.

Friday, April 29, 2016

A Repellent Argument

#11,323

While the CDC, the media, and most of the residents of the lower 48 states wait to see how much of an impact the Zika virus will have this summer in the U.S., it is worth noting that last summer - during just a moderately active year - we saw more than 1,300 hospitalizations and 119 deaths from the West Nile Virus.

While only about 20% of the people who are infected with WNV develop symptoms – and most only experience a mild flu-like illness (and are therefore rarely counted) – a very small percentage go on to develop a more severe, and sometimes deadly, `neuroinvasive’ form of WNV.

The CDC summarized last year's WNV activity:

As of January 12, 2016, a total of 48 states and the District of Columbia have reported West Nile virus infections in people, birds, or mosquitoes in 2015.

Overall, 2,060 cases of West Nile virus disease in people have been reported to CDC. Of these, 1,360 (66%) were classified as neuroinvasive disease (such as meningitis or encephalitis) and 700 (34%) were classified as non-neuroinvasive disease.

Bad, but not as bad as 2012. where we saw :

A total of 5,674 cases of West Nile virus disease in people, including 286 deaths, were reported to CDC. Of these, 2,873 (51%) were classified as neuroinvasive disease (such as meningitis or encephalitis) and 2,801 (49%) were classified as non-neuroinvasive disease.

On top of that, each year we usually see a smattering of EEE (Eastern Equine Encephalitis) cases, along with some La Crosse virus (LACV), Jamestown Canyon virus (JCV) and St. Louis Encephalitis (STLV) infections. Small outbreaks of Dengue and Chikungunya are even possible.

And we haven't even touched on the tick borne infections, like Lyme Disease, which the CDC estimates may affect as many as 300,000 Americans every year.

The CDC maintains a long (and growing) list of of tick spread pathogens found in North America, including:

Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis, Borrelia miyamotoi, Colorado tick fever, Ehrlichiosis, Heartland virus, Lyme disease, Powassan disease, Rickettsia parkeri rickettsiosis ,Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF), STARI (Southern tick-associated rash illness)Tickborne relapsing fever (TBRF), Tularemia,364D rickettsiosis

To this growing rogues gallery, we recently added Borrelia mayonii, which has recently been discovered to be causing a Lyme-like illness in Minnesota and Wisconsin (see CDC: New Lyme-Disease-Causing Bacteria Species Discovered).

To this Florida boy who spent a lot of time in the woods camping and hiking (often without repellents) - and who saw nary a tick or chigger bite in all those years (mosquitoes, yes) - all of this seems a bit surreal.

Although it seems counter-intuitive, in our increasingly urbanized and modernized society the threat of vector-borne diseases has grown greater over the past couple of decades, as has our need to take steps to prevent them.

With summer-like weather either here or on the way, now is the time to consider how you will protect yourself and your family members from these vector borne threats.

For mosquitoes, health departments advise you follow the 5 D's.

While the CDC recommends for ticks:

While it is a good idea to take preventive measures against ticks year-round, be extra vigilant in warmer months (April-September) when ticks are most active.

Avoid Direct Contact with Ticks

- Avoid wooded and brushy areas with high grass and leaf litter.

- Walk in the center of trails.

Repel Ticks with DEET or Permethrin

- Use repellents that contain 20 to 30% DEET (N, N-diethyl-m-toluamide) on exposed skin and clothing for protection that lasts up to several hours. Always follow product instructions. Parents should apply this product to their children, avoiding hands, eyes, and mouth.

- Use products that contain permethrin on clothing. Treat clothing and gear, such as boots, pants, socks and tents with products containing 0.5% permethrin. It remains protective through several washings. Pre-treated clothing is available and may be protective longer.

- Other repellents registered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Find and Remove Ticks from Your Body

- Bathe or shower as soon as possible after coming indoors (preferably within two hours) to wash off and more easily find ticks that are crawling on you.

- Conduct a full-body tick check using a hand-held or full-length mirror to view all parts of your body upon return from tick-infested areas. Parents should check their children for ticks under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and especially in their hair.

- Examine gear and pets. Ticks can ride into the home on clothing and pets, then attach to a person later, so carefully examine pets, coats, and day packs.

- Tumble clothes in a dryer on high heat for an hour to kill remaining ticks. (Some research suggests that shorter drying times may also be effective, particularly if the clothing is not wet.)

To help you decide on a repellent, the EPA has created an interactive insect repellent search engine that will allow you to input your needs and it will spit out the best ones for you to use.

While the old school vector borne illnesses like Lyme Disease, Ehrlichiosis, or WNV may not inspire the same kind of fear and media coverage as Zika, they are nothing to take lightly, and in many cases can be avoided by taking a few simple precautions.

While Zika will likely get star billing, we'll be following all of these vector borne diseases all summer long in AFD.

Wisconsin: Infant At Children's Hospital Tests Positive For Elizabethkingia

#11,322

For the past two months we've been following a multi-state community outbreak of Elizabethkingia bacterial infection among mostly elderly residents in Wisconsin, Illinois and Michigan.

Although it isn't immediately clear whether this is connected to the larger outbreak we've been following - or is even the same strain - overnight local media are reporting an Elizabethkingia infection in an infant at the neonatal unit of Children's Hospital.

The genus Elizabethkingia includes not only E. Anophelis , but also E. meningoseptica, E. miricola, and E. endophytica. Most cases in the literature have involved HAI's (Hospital Acquired Infections), and community outbreaks are rare.

This from the Milwaukee News.

A strain of the Elizabethkingia bacteria has been found in an infant being treated in the neonatal intensive care unit at Children's Hospital of Wisconsin, the hospital confirmed Thursday.

It appears to be the first case involving a child in what has become the largest known outbreak of its kind in the country.

To date, 18 people have died, most of them over the age of 65. All had severe chronic conditions, such as cancer, renal disease, cirrhosis and diabetes.

Children's Hospital said there was no indication that the child's infection is serious, and that no additional precautions are necessary because the bacteria is not easily transmitted from person to person.

(Continue . . . )

Hopefully we'll get a clarification on this case in the next few days. In the meantime, the latest Wisconsin DOH update adds two additional cases.

Wisconsin 2016 Elizabethkingia anophelis outbreak

The Wisconsin Department of Health Services (DHS), Division of Public Health (DPH) is currently investigating an outbreak of bacterial infections caused by Elizabethkingia anophelis.

The majority of patients acquiring these infections are over 65 years old, and all patients have a history of at least one underlying serious illness.

The Department quickly identified effective antibiotic treatment for Elizabethkingia, and has alerted health care providers, infection preventionists and laboratories statewide. Since the initial guidance was sent on January 15, there has been a rapid identification of cases and healthcare providers have been able to treat and improve outcomes for patients. DHS continues to provide updates of outbreak-related information that includes laboratory testing, infection control and treatment guidance.

At this time, the source of these infections is still unknown, and the Department continues to work diligently to control this outbreak. Disease detectives from the Department and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are conducting a comprehensive investigation which includes:

- Interviewing patients with Elizabethkingia anophelis infection and/or their families to gather information about activities and exposures related to healthcare products, food, water, restaurants, and other community settings.

- Obtaining environmental and product samples from facilities that have treated patients with Elizabethkingia anophelis infections. To date, these samples have tested negative and there is no indication the bacteria was spread by a single healthcare facility.

- Conducting a review of medical records.

- Obtaining nose and throat swabs from individuals receiving care on the same units in health care facilities as a patient with a confirmed Elizabethkingia anophelis to determine if they are carrying the bacteria. To date, all of these specimens tested negative, which suggests the bacteria is not spreading from person to person in healthcare settings.

- Obtaining nose and throat swabs from household contacts of patients with confirmed cases to identify if there may have been exposure in their household environment.

- Performing a “social network” analysis to examine any commonalities shared between patients including healthcare facilities or shared locations or activities in the community.

Affected counties include Columbia, Dane, Dodge, Fond du Lac, Jefferson, Milwaukee, Ozaukee, Racine, Sheboygan, Washington, Waukesha and Winnebago.

There have been 18 deaths among individuals with confirmed Elizabethkingia anophelis infections and an additional 1 death among possible cases for a total of 19 deaths. It has not been determined if these deaths were caused by the infection or other serious pre-existing health problems. Counties where these deaths occurred are: Columbia, Dodge, Fond du lac, Milwaukee, Ozaukee, Racine, Sheboygan, Washington and Waukesha.

*This investigation is ongoing. Case counts may change as additional illnesses are identified and more cases are laboratory confirmed.

**These are cases that tested positive for Elizabethkingia, but will never be confirmed as the same strain of Elizabethkingia anophelis because the outbreak specimens are no longer available to test.

CDC: Updated Zika Numbers For The United States

|

| Laboratory-confirmed Zika virus disease cases reported to ArboNET by state or territory — United States, 2015–2016 (as of April 27, 2016) |

#11,321

The CDC has posted the latest weekly figures on Zika Virus Disease in the United States, and while it is still early in the year for vector transmission in the lower 48, there are 8 sexually transmitted cases documented, and 436 travel related cases (including 36 pregnant women).

Florida leads the country with 90 imported cases, up by 6 from last week's report.

Among the territories, Puerto Rico leads with 570 lab-confirmed cases, an increase of 20% over last week. Follow the link below for the full report, including a state-by-state listing.

As of April 27, 2016 (5 am EST)

- Zika virus disease and Zika virus congenital infection are nationally notifiable conditions.

- This update from the CDC Arboviral Disease Branch includes provisional data reported to ArboNET for January 1, 2015 – April 27, 2016.

US States

US Territories

- Travel-associated Zika virus disease cases reported: 426

- Locally acquired vector-borne cases reported: 0

- Total: 426

- Pregnant: 36

- Sexually transmitted: 8

- Guillain-Barré syndrome: 1

- Travel-associated cases reported: 3

- Locally acquired cases reported: 596

- Total: 599

- Pregnant: 56

- Guillain-Barré syndrome: 5

Thursday, April 28, 2016

WHO Zika Sitrep - April 28th

#11,320

The World Health Organization has posted its weekly Sitrep on Zika, Microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome. This Sitrep also includes brief updates on Yellow Fever and Ebola in Africa.

I've only posted the summary, follow the link to download and read the full 10-page PDF report.

Zika situation report

28 April 2016

Zika virus, Microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome

Summary:

As of 27 April, 55 countries and territories report continuing mosquito-borne transmission; for 42 countries this is their first documented Zika virus outbreak (Fig. 1).

Mosquito-borne transmission (Table 1):

- 42 countries are experiencing a first outbreak of Zika virus since 2015, with no previous evidence of circulation, and with ongoing transmission by mosquitos.

- 13 countries reported evidence of Zika virus transmission between 2007 and 2014, with ongoing transmission.

- Four countries or territories have reported an outbreak since 2015 that is now over: Cook Islands, French Polynesia, ISLA DE PASCUA – Chile and YAP (Federated States of Micronesia.

Person-to-person transmission:

- Nine countries have reported evidence of person-to-person transmission of Zika virus, probably via a sexual route.

- In the week to 27 April, no additional countries reported mosquito-borne Zika virus transmission. Canada is the latest country to report person-to-person transmission.

- Microcephaly and other fetal malformations potentially associated with Zika virus infection or suggestive of congenital infection have been reported in six countries or territories (Table 3). Two cases, each linked to a stay in Brazil, were detected in Slovenia and the United States of America. One additional case, linked to a brief stay in Mexico, Guatemala and Belize, was detected in a pregnant woman in the United States of America.

- In the context of Zika virus circulation, 13 countries and territories worldwide have reported an increased incidence of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) and/or laboratory confirmation of a Zika virus infection among GBS cases.

- Based on research to date, there is scientific consensus that Zika virus is a cause of microcephaly and GBS.

- The global prevention and control strategy launched by the World Health Organization as a Strategic Response Framework encompasses surveillance, response activities and research. Key interventions are being undertaken jointly by WHO and international, regional and national partners in response to this public health emergency.

- WHO has developed new advice and information on diverse topics in the context of Zika virus. WHO’s latest information materials, news and resources to support risk communication, and community engagement are available online.

Credit WHO

MMWR: Epidemiological Investigation Into A Case Of Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis

#11,319

Although extremely rare, nearly every summer we hear of a handful of cases of PAM (Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis), caused by an amoebic parasite called Naegleria Fowleri. Between 1962 and 2014 there were 133 cases of Naegleria Fowleri infection reported in the United States, with all but 3 of them fatal.

Until a few years ago, nearly all of the Naegleria infections reported in the United States were linked to swimming in warm, stagnant freshwater ponds and lakes (see Naegleria Fowleri: Rare, Deadly & Avoidable).

In 2011, however, we saw two cases reported in Neti pot users from Louisiana, prompting the Louisiana Health Department to recommend that people `use distilled, sterile or previously boiled water to make up the irrigation solution’ (see Neti Pots & Naegleria Fowleri) and a 4 year-old infected in 2013, through contact with the municipal water supply.

Although mostly seen in the southern states (see map above), infections have occurred as far north as Minnesota.

While not a hotbed of activity, last summer we saw a case in California (see CBS News Central California Woman, 21, Dies From Brain-Eating Amoeba) involving a 21 year old woman. At the time, few details were available on how she came to be infected.

Today the CDC's MMWR carries a Notes from the Field report on the epidemiological investigation, which suggests a poorly chlorinated spring-fed swimming pool was the likely source of infection.

This is an unusual finding, and furthers the recent pattern of seeing PAM cases arise from atypical settings (Northern states, via neti pots and municipal water supplies, etc.) in the United States.

I've only posted some brief excerpts, so follow the link to read it in its entirety. When you return, I'll have a bit more.

Notes from the Field: Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis Associated with Exposure to Swimming Pool Water Supplied by an Overland Pipe — Inyo County, California, 2015

Weekly / April 29, 2016 / 65(16);424

Richard O. Johnson, MD1; Jennifer R. Cope, MD2; Marvin Moskowitz3; Amy Kahler, MS2; Vincent Hill, PhD2; Kaleigh Behrendt1; Louis Molina4; Kathleen E. Fullerton, MPH2; Michael J. Beach, PhD2 (View author affiliations)

On June 17, 2015, a previously healthy woman aged 21 years went to an emergency department after onset of headache, nausea, and vomiting during the preceding 24 hours. Upon evaluation, she was vomiting profusely and had photophobia and nuchal rigidity. Analysis of cerebrospinal fluid was consistent with meningitis.* She was empirically treated for bacterial and viral meningoencephalitis.

Her condition continued to decline, and she was transferred to a higher level of care in another facility on June 19, but died shortly thereafter. Cultures of cerebrospinal fluid and multiple blood specimens were negative, and tests for West Nile, herpes simplex, and influenza viruses were negative. No organisms were seen in the cerebrospinal fluid; however, real-time polymerase chain reaction testing by CDC was positive for Naegleria fowleri, a free-living thermophilic ameba found in warm freshwater that causes primary amebic meningoencephalitis, an almost universally fatal infection.

(SNIP)

This represents the first time this type of exposure to N. fowleri has been reported in the United States and continues to highlight the changing epidemiology and expanding geography of this pathogen (1,2). In Australia, several cases in the 1960s and 1970s related to nasal exposure with untreated drinking water piped for hundreds of miles overland were reported (3). This case highlights the importance of operating and maintaining properly treated swimming pools (http://www.cdc.gov/healthywater/swimming/protection/pool-user-tips-factsheet.html) and the role of water distribution systems as potential environments for the proliferation of N. fowleri.

Up until a recently, infection with Naegleria Fowleri was universally fatal, but in 2013 an investigational drug called miltefosine was used successfully for the first time to treat the infection. Early diagnosis, and administration of this drug, are crucial however. The CDC advises:

Treatment

Clinicians: For 24/7 diagnostic assistance, specimen collection guidance, shipping instructions, and treatment recommendations, please contact the CDC Emergency Operations Center at 770-488-7100.

Clinicians: CDC now has an investigational drug called miltefosine available for treatment of free-living ameba (FLA) infections caused by Naegleria fowleri, Balamuthia mandrillaris, and Acanthamoeba species. If you have a patient with suspected FLA infection, please contact the CDC Emergency Operations Center at 770-488-7100 to consult with a CDC expert regarding the use of this drug.

And finally, despite the unusual modes of infection over the past few years, the most common way to contract this amoeba is from swimming in warm, stagnant, fresh water. The State of Florida advises:

The only known way to prevent Naegleria fowleri infections is to refrain from water-related activities. However, some common-sense measures that might reduce risk by limiting the chance of contaminated water going up the nose include:

- Avoiding water-related activities in bodies of warm freshwater, hot springs, and thermally-polluted water such as water around power plants.

- Avoiding water-related activities in warm freshwater during periods of high water temperature and low water levels.

- Holding the nose shut or using nose clips when taking part in water-related activities in bodies of warm freshwater such as lakes, rivers, or hot springs.

- Avoiding digging or stirring up sediment while taking part in water-related activities in shallow, warm freshwater areas.

Recreational water users should assume that there is always a low-level of risk associated with entering all warm fresh water in southern tier states. Because the location and number of ameba in the water can vary a lot over time, posting signs is unlikely to be an effective way to prevent infections. In addition, posting signs on only some fresh water bodies might create a misconception that bodies of water that are not posted are Naegleria-free.

PLoS One: Influenza Seasonality In The Tropics & Subtropics

|

| Influenza seasonality patterns—number of peaks and identifiable year-round activity. - PLoS One |

#11,318

While much of the Northern and Southern hemisphere have well defined influenza seasons - generally aligned with winter - for much of the tropics and parts of the subtropics winter is far less well defined, and their flu season more variable.

As we discussed recently in It's Always Flu Weather (Somewhere), influenza can circulate year-round in some tropical regions, and Hong Kong often sees a biphasic or `double peaked’ flu season (see Hong Kong Girds For More Flu).All of which makes choosing between the northern and southern flu vaccine compositions, and the timing of flu vaccinations, in much of the world a matter of some concern.

At the top of this blog you'll find a fascinating map - the most detailed to date - that charts the variability of flu transmission across much of the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

One of the surprises: 37 of 70 countries classified had one distinct influenza peak each year, while 17 had two - making Hong Kong's biphasic flu season more common than previously believed.

First a link to the PLoS One study, followed by a press release from the CDC which collaborated on this research.

Siddhivinayak Hirve ,Laura P. Newman,John Paget,Eduardo Azziz-Baumgartner, Julia Fitzner,Niranjan Bhat,Katelijn Vandemaele,Wenqing Zhang

Published: April 27, 2016 http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0153003Abstract

Background

The timing of the biannual WHO influenza vaccine composition selection and production cycle has been historically directed to the influenza seasonality patterns in the temperate regions of the northern and southern hemispheres. Influenza activity, however, is poorly understood in the tropics with multiple peaks and identifiable year-round activity. The evidence-base needed to take informed decisions on vaccination timing and vaccine formulation is often lacking for the tropics and subtropics. This paper aims to assess influenza seasonality in the tropics and subtropics. It explores geographical grouping of countries into vaccination zones based on optimal timing of influenza vaccination.

(Continue . . . )

A new collaborative study by CDC and global health partners published today in the journal PLOS ONE examined the timing of influenza virus circulation in 138 tropical and sub-tropical countries and territories and provided new evidence which may help inform the choice of influenza vaccine formulation and the timing of vaccination campaigns.

Historically, the timing of the bi-annual World Health Organization (WHO) influenza vaccine composition selection and production cycle has been directed by the influenza seasonality patterns in the temperate regions of the northern and southern hemispheres. Influenza activity in the tropics and sub-tropics has been less well defined because these countries often identify influenza throughout the year and some have multiple peaks of influenza activity each year.

However, in recent years, influenza surveillance has improved in many countries, providing the opportunity for researchers to better define influenza seasonality. The study results have significant implications for the increasing number of low- and middle-income countries in the tropics and sub-tropics which over the last decade have begun introducing seasonal influenza vaccination into their immunization programs or are expanding their programs to include maternal influenza immunization, especially in the Latin American region.

Periods of peak flu activity were identified for 70 of the 138 countries examined, representing about 73% of the world’s population. Thirty-seven countries had one distinct influenza peak and 17 countries had two distinct peaks each year. Countries near the equator often identify influenza throughout the year and had secondary peaks. Researchers determined that most countries in Central and South America, South and Southeast Asia experienced a primary period of influenza activity from April to June. India showed an additional secondary peak between October and December. Africa presented a complex picture with increased activity from October to December in the northern region, from April to June in the southern region and throughout the year in sub-Saharan countries near the equator.

These findings suggest that optimal timing for an annual seasonal influenza vaccination campaign could be identified for most countries in the tropics and sub-tropics. A southern hemisphere formulation is recommended to be given in April for most of Central and South America (with the exception of Guatemala, Jamaica and Mexico), sub-Saharan Africa (with the exception of the Democratic Republic of Congo, Malawi, Rwanda and the United Republic of Tanzania), and tropical Asia (with the exception of Sri Lanka and Indonesia). A northern hemisphere formulation is recommended to be given in October for northern Africa and the Middle East up to Pakistan. Countries such as Brazil, China and India which have varied flu seasonality and countries near the equator with year-round influenza activity could explore the marginal benefit of alternate vaccination times based on local flu seasonality.

The study was conducted using four different statistical approaches by researchers from CDC, Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL), Program for Appropriate Technology (PATH) and the WHO. Researchers analyzed laboratory-confirmed influenza activity data for the seasons 2010 to 2015 from the WHO’s FluNet reporting system, the largest global database for influenza virological surveillance data. National surveillance data for the seasons 2002 to 2014 were also used, where available. Influenza pandemic years 2009-2010 were excluded, as this time period was not seasonal by definition.

While the study has proposed simplified operational guidance to countries in the tropics and sub-tropics, researchers emphasize that once the timing of vaccination is determined by local seasonality, the most recent WHO influenza virus vaccine recommendation should be used, regardless of the geographic location of the country.

This study is available online in PLOS ONE.

EID Journal: Human Adenovirus Associated with Severe Respiratory Infection, Oregon, USA, 2013–2014

|

| Adenovirus - Credit CDC |

#11,317

Despite our focus on influenza each year, it is far from being the only respiratory virus capable of causing severe outbreaks. It is, however, capable of substantial virulence and is highly mutable, making it both an annual visitor and (on rare occasions) a pandemic threat.

Other respiratory viruses of concern include human rhinoviruses, human metapneumovirus, RSV, parainfluenza viruses, coronaviruses, and adenoviruses (see A Plethora Of Pathogens, Even During A Pandemic).

To give you an idea of how common some of these viruses really are, a little over two years ago Dr. Ian Mackay produced the following graphic on his VDU blog.

As you can see, adenoviruses were more commonly detected than influenza.

Ubiquitous in humans and animals, hardy survivors outside of a host, and able to circulate year-round, the 52 known serotypes of adenovirus can cause a wide spectrum illness, ranging from asymptomatic carriage, to mild `cold-like' symptoms, up to severe pneumonia.

Interestingly, a person can have – and shed – adenovirus for weeks or even months without showing symptoms. The virus was first isolated from the adenoids in 1953, hence its name.

While no vaccine is currently available for the public, the military is using a recently approved (March, 2011) oral vaccine against types 4 and 7 on new recruits to help prevent outbreaks.

Over the years we’ve followed a few high-profile outbreaks of adenovirus infection, including 2012's China: Hebei Outbreak Identified As Adenovirus 55, and a multi-state outbreak of virulent serotype Ad14 a decade ago (see 2007 MMWR Acute Respiratory Disease Associated with Adenovirus Serotype 14 --- Four States, 2006—2007).

All of which serves as prelude to a recently published EID Journal research report on a reemerging human adenovirus called HAdV-B7.

Research

Human Adenovirus Associated with Severe Respiratory Infection, Oregon, USA, 2013–2014

Magdalena Kendall Scott, Christina Chommanard, Xiaoyan Lu, Dianna Appelgate, LaDonna Grenz, Eileen Schneider, Susan I. Gerber, Dean D. Erdman, and Ann Thomas

Abstract

Several human adenoviruses (HAdVs) can cause respiratory infections, some severe. HAdV-B7, which can cause severe respiratory disease, has not been recently reported in the United States but is reemerging in Asia.

During October 2013–July 2014, Oregon health authorities identified 198 persons with respiratory symptoms and an HAdV-positive respiratory tract specimen. Among 136 (69%) hospitalized persons, 31% were admitted to the intensive care unit and 18% required mechanical ventilation; 5 patients died.

Molecular typing of 109 specimens showed that most (59%) were HAdV-B7, followed by HAdVs-C1, -C2, -C5 (26%); HAdVs-B3, -B21 (15%); and HAdV-E4 (1%). Molecular analysis of 7 HAdV-B7 isolates identified the virus as genome type d, a strain previously identified only among strains circulating in Asia.

Patients with HAdV-B7 were significantly more likely than those without HAdV-B7 to be adults and to have longer hospital stays. HAdV-B7 might be reemerging in the United States, and clinicians should consider HAdV in persons with severe respiratory infection.

(SNIP)

HAdV type surveillance is an important tool for monitoring changes in predominant types and genome types. Shifts in HAdV types might be associated with more severe disease not only in vulnerable populations, such as children, elderly persons, and immunocompromised persons, but might also cause community outbreaks of severe respiratory disease in adults, as occurred in Oregon. Healthcare providers should consider HAdV in their differential diagnosis for patients with pneumonia and acute respiratory infection. Testing for HAdV using respiratory panel PCR assays and HAdV typing has been increasing nationwide. In response, CDC recently launched a voluntary and passive surveillance system to collect HAdV typing data from laboratories called the National Adenovirus Type Reporting System. The main objectives of this system are to better define circulation patterns of HAdV types and better monitor HAdV outbreaks in the United States.

HAdV-B7 might be reemerging in the United States and might be associated with increased numbers of severe respiratory infections. Tracking the emergence of HAdV types in the United States will lead to early identification of new types and potential variants of known types. Our results demonstrate how HAdV surveillance might help explain clusters and sporadic cases of severe illness possibly related to changes in HAdV species.

Ms. Kendall Scott is the influenza epidemiologist for OPHD. Her research interests include influenza and other respiratory viruses.

(Continue . . . )

The number of `known’ respiratory viruses increases practically every year, due to advances in microbiology and sequence-independent amplification of viral genomes. There is, no doubt, much more to discover about the myriad of non-influenza respiratory viruses in circulation around the world.

Most will prove to be clinically indistinguishable from the respiratory viruses we already know, producing mostly mild `cold-like' symptoms.

But as we saw with SARS-CoV in 2003, HEV68 in 2008-10, MERS-CoV in 2012, and EV-D68 in 2014, they can occasionally surprise. Which makes the surveillance and identification of these respiratory viruses more than just of academic interest.

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

EID Journal: Antibody Response & Disease Severity In HCW MERS Survivors

|

| Credit WHO |

#11,316

Despite there having been more than 1,100 known survivors of MERS-CoV infection (mostly in Saudi Arabia), we've seen very little in the way of post-convalescent follow up on these cases.

Aside from obvious concerns over post-MERS Sequelae, another area of interest is the level, and persistence, of MERS antibodies among the survivors. While viral infections usually leave behind some degree of immunity in the recovered host, their effectiveness and longevity can vary widely

And among camels, at least (see MERS Coronavirus in Dromedary Camel Herd, Saudi Arabia and EID Journal: Replication & Shedding Of MERS-CoV In Inoculated Camels) - we've seen some limited evidence of repeat infections.

Today the EID Journal looks at 9 Health care workers who were infected during the 2014 Jeddah outbreak (2 severe pneumonia, 3 milder pneumonia, 1 URTI, and 3 asymptomatic), and finds that only those with severe pneumonia still carried detectable levels of antibodies 18 months later.

Those who experienced a milder pneumonia had shorter lived antibody responses (1 out to 10 months, 2 out to 3 months), while the URTI and asymptomatic cases tested negative at 3 months post infection.

While a small study, if the results hold true on a larger scale this raises some interesting questions, including:

- Are those who only experienced mild or moderate illness at risk of re-infection?

- Would convalescent plasma donated by those without severe illness be ineffective?

- Does this skew (under count) the community seroprevalence studies we've seen coming out of Saudi Arabia and Kenya?

- How will all of this play into the development of a MERS-CoV vaccine (for camels or humans)?

Volume 22, Number 6—June 2016

Dispatch

Antibody Response and Disease Severity in Healthcare Worker MERS Survivors

Abeer N. Alshukairi, Imran Khalid, Waleed A. Ahmed, Ashraf M. Dada, Daniyah T. Bayumi, Laut S. Malic, Sahar Althawadi, Kim Ignacio, Hanadi S. Alsalmi, Hail Al-Abdely, Ghassan Y. Wali, Ismael A. Qushmaq, Basem M. Alraddadi, and Stanley Perlman

Abstract

A study evaluating the immune response in patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) showed antivirus antibodies in survivors can be detected by ELISA and immunofluorescence assay (IFA) for up to 24 months after infection (1). Another study revealed that SARS-CoV antibodies were not detectable at 6 years after infection (2). Antibody response to Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) typically is detected in the second and third week after the onset of the infection (3–5), but little is known about the longevity of the response or whether the decrease in antibody response over time correlates with the severity of the initial infection. We conducted a longitudinal study of antibody response among a cohort of MERS survivors who had been treated at King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (KFSHRC-J).

We studied antibody response in 9 healthcare workers in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, who survived Middle East respiratory syndrome, by using serial ELISA and indirect immunofluorescence assay testing. Among patients who had experienced severe pneumonia, antibody was detected for >18 months after infection. Antibody longevity was more variable in patients who had experienced milder disease.

(SNIP)

The 2 patients with severe pneumonia had the highest antibody titers detected among all patients and remained MERS-CoV-antibody–positive when tested at 18 months after illness onset. They also had prolonged viral shedding documented by persistent positive rRT-PCR results for 13 days (patient 1) and 12 days (patient 2); rRT-PCR analyses were negative after 2–5 days for patients 4–9. rRT-PCR was only repeated at day 13 for patient 3, and the result was negative.

Three patients with pneumonia were MERS-CoV-antibody–positive at 3 months, but antibody was detected in only 1 of the 3 at 10 months (Table). All patients who had an upper respiratory tract function or remained asymptomatic had no detectable antibody response on the basis of ELISA and IFA results.

(Excerpt)

In conclusion, our results indicate that MERS-CoV antibody persistence depends on disease severity. Further studies are required to determine the role of the virus-specific T-cell response in MERS patients and determine whether patients with mild infections are at risk for reinfection and would therefore benefit from vaccination. Our data also show that potential donors of MERS-CoV convalescent-phase serum samples are limited to patients who recover from severe pneumonia.

Dr. Alshukairi is an infectious diseases consultant at KFSHRC-J. Her interests include tuberculosis and infections in immunocompromised hosts.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mohamma Rasmi Gabajah for help in obtaining blood samples from HCWs.

This work was supported by the Pathology Department at KFSHRC-J. S.P. was supported by a grant from the US National Institutes of Health (grant no. PO1 AI060699).

Japan's Earthquake Preparedness Messaging - Tokyo's X Day

# 11,315

For decades millions of residents in and around Tokyo Japan have lived with the knowledge that someday another major earthquake - like the M7.9 quake that struck shortly before noon on September 1st, 1923 - will again level the city.

The timing of the 1923 quake, at lunchtime, meant many people were cooking over open fires when it struck, and that – combined with winds from an offshore typhoon – contributed to the firestorm that swept Tokyo.

Estimates vary, but more than 100,000 people are believed to have perished. Since 1960, September 1st has been designated as an annual "Disaster Prevention Day" across all of Japan, an event that is taken very seriously nationwide.

But as memories of old disasters fade, the risk of seeing the next one grows nearer.

Like Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle - Tokyo has lived under the specter of the `big one' for decades, and finding ways to keep the preparedness message fresh, alive, and relevant for each new generation is a major challenge.

Faced with a similar dilemma five years ago, our own CDC launched a preparedness campaign where Zombies became a metaphor for an unthinkable disaster.

For more on this highly successful campaign, see The CDC And The Zombie Apocalypse, which eventually expanded into a 2-part Graphic Novel preaching preparedness, and a number of tie-in posters and T-Shirts.

Given the universal popularity of Manga - highly stylized graphic novels - which are read by people of all ages in Japan, and encompass a broad range of genres - it only makes sense that the Tokyo Metropolitan Government would use this medium to promote earthquake preparedness.

Particularly in light of several recent major quakes on the southern island of Kyushu, and predictions by leading seismologists that `the big one' grows more likely for Tokyo with every passing day. A few previous blogs on the topic include:

Academics Debate Odds Of Tokyo Earthquake

Japan: Quake/Tsunami Risks Greater Than Previously Thought

Today Bloomberg News carried a report (Tokyo Races Against Quake That Will Shake World on `X' Day) that examines Tokyo's preparedness and messaging efforts, and mentions both the Earthquake Manga and a 300-page citizens preparedness guide.

The article only linked to the Japanese version of the Manga - so I started poking around the Tokyo Metro Government website until I found an English language version of both the full 300 page preparedness guide (see below) and Manga.

Disaster Preparedness Tokyo

The Tokyo Metropolitan Government has compiled a manual called “Disaster Preparedness Tokyo” (Tokyo Bousai*) to help households get fully prepared for an earthquake directly hitting Tokyo and other various disasters.

“Disaster Preparedness Tokyo” is tailored to the various local features of Tokyo, its urban structure, and the lifestyles of its residents, and contains easy-to-understand information on how to prepare for and respond to a disaster.This information will be useful now and in the event of an emergency.

*“Bousai” is Japanese for “disaster preparedness”Cover(PDF:130KB)

Introduction, Table of Contents, Symbol Mark(PDF:1.3MB)

01 Simulation of a Major Earthquake (P14-79) (PDF:3.9MB)

02 Let's Get Prepared

Disaster Preparedness Actions (P80-141) (PDF:3.7MB)

03 Other Disasters and Countermeasures (P142-173) (PDF:1.3MB)

04 Survival Tips (P174-235) (PDF:3.1MB)

05 Disaster Facts and Information You Should Know (P236-321) (PDF:1.9MB)

Manga comic: "TOKYO 'X' DAY" (PDF:4.5MB)

Tokyo Metropolitan Disaster Prevention Map

Although geared for a Japanese audience, this incredibly detailed Earthquake & disaster guide would be of value to anyone, no matter where they live. It also has brief sections on surviving floods, tornadoes, volcanic eruptions, terrorist attacks and even pandemics.

For a California-centric guide, you will want to check out the 100 page L. A. County Emergency Survival Guide.

Sunday, April 30th marks America's Preparathon!, and FEMA, Ready.gov, the CDC, and a bevy of other state and federal agencies would love it if Americans took individual preparedness as seriously as the residents of Japan.

FEMA http://www.fema.gov/index.shtm

READY.GOV http://www.ready.gov/

AMERICAN RED CROSS http://www.redcross.org/

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)