For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong. - H. L. Mencken

#15,089

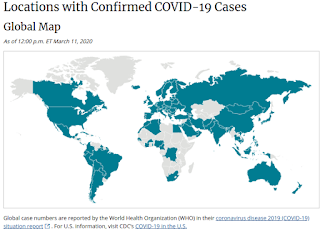

Although the writing on the wall has been quite legible to many of us for the better part of two months, this seems to be the week that most in the western world have finally woken up to the idea that we are facing a genuine, and quite serious pandemic.

All it's taken has been a stock market crash, the closure of scores of colleges and universities, the cancellation of March Madness and the NBA season, and the shuttering of Disneyland. All subtle hints that something is amiss.Somewhat incredibly, even at this late date, there are still millions of people in denial. At least if the `meme army' on twitter is any indication. We are seeing fewer and fewer comparisons of COVID-19 to seasonal flu, but even so, few seem to realize that this isn't going to blow over in a few weeks, and then life goes back to normal.

This is, of course, the sort of messaging that many countries - at least outside of the current `hot zones' - have been projecting. This week I've heard several U.S. officials warn that `we haven't seen the peak in cases, quite yet'.

As if we are anywhere near the peak. Folks, we are barely into the foothills.I suppose they think this is a way of breaking bad news `gently' - an approach that might be appropriate if you were talking to a 4 year old - but not when discussing a serious, potentially life-threatening event with adults.

As a result, we've squandered 2 valuable months of lead time. Time to prepare, mentally and logistically, for what is likely to become a long viral siege.

And no, this isn't just an American problem. This denialism runs deep around the world. Everyone - with the exception of Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Singapore - has been badly behind the curve on this pandemic threat.Due in large part, I suspect, to what the Risk Communications tag-team duo of Peter Sandman and Jody Lanard previously dubbed `Failures of the Imagination', in the following essay on the world's response (and lack, thereof) to the Ebola epidemic in West Africa in 2014.

While this essay deals with specific time, place, and pathogen it's lessons can be applied to our current - and probably any future - pandemic threat. I've only included an excerpt, so follow the link to read it in its entirety.

Ebola: Failures of Imagination

by Jody Lanard and Peter M. Sandman

The alleged U.S. over-reaction to the first three domestic Ebola cases in the United States – what Maryn McKenna calls Ebolanoia – is matched only by the world’s true under-reaction to the risks posed by Ebola in Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Guinea. We are not referring to the current humanitarian catastrophe there, although the world has long been under-reacting to that.

We will speculate about reasons for this under-reaction in a minute. At first we thought it was mostly a risk communication problem we call “fear of fear,” but now we think it is much more complicated.

Some of the world’s top Ebola experts say they are worrying night and day about the possibility of endemic Ebola, a situation in which Ebola will continue to spread, and then presumably wax and wane repeatedly, in West Africa.

They – and we – find it difficult to understand why Ebola has not yet extended into Cote d’Ivoire, Mali, and Guinea-Bissau. (After we drafted this on October 23, a case was confirmed in Mali.)

Fewer experts refer publicly to what we think must frighten them even more (and certainly frightens us even more): the prospect of Ebola sparks landing and catching unnoticed in slums like Dharavi in Mumbai or Orangi Town in Karachi – or perhaps Makoko in Lagos. (Imagine how different recent history might have been if the late Ebola-infected Minnesota resident Patrick Sawyer had started vomiting in Makoko instead of at Lagos International Airport on July 20.)

(Continue . . . )

Our inability to seriously consider even a watered-down, and oxymoronic `reasonable worst-case scenario', leaves us open to incredible damage. One of my criticisms of the 2006-2008 pandemic planning around the world was far too many states and agencies were planning for a repeat of 1968 or 1957, not 1918.

Imagine if your big city fire department only trained for and was equipped to deal with average-sized fires, or if our military only prepared for `reasonable worst-case, and easily winnable conflicts'?Sadly, despite billions of dollars of tax dollars spent, that is where we find ourselves with pandemic preparedness. We always seem intent on preparing to fight the last pandemic, not the next one.

Yes, there have been many people, organizations, and agencies around the world who have clamored for realistic preparedness for a severe pandemic. You can find dozens of examples in this blog, including:

JHCHS Pandemic Table Top Exercise (EVENT 201) Videos Now Available Online

Center for Health Security Report On Preparedness for A High-impact Respiratory Pathogen

#NatlPrep: Personal Pandemic Preparedness

CLADE X: Archived Video & Recap)

Almost 2 months ago (January 18th), in response to what was happening in Hubei Province China, experts were already sounding the alarm (see JHCHS, The Gates Foundation & WEF: 7 Pandemic Preparedness Recommendations In A Joint Call to Action).

But instead of action, governments around the world have dithered, unable to believe that a truly serious pandemic could happen `on their watch'.But it is not just our current crop of leaders that are to blame. We can look back to the damning 2006 Campbell Commission SARS report, on the failures of hospitals to protect their workers during the 2003 outbreak in Ontario, which offered one overriding piece of advice:

Most important, the problems include Ontario’s failure to recognize in hospital worker safety the precautionary principle that reasonable action to reduce risk, like the use of a fitted N95 respirator, need not await scientific certainty. – SARS Commission Executive Summary.

In 2009 the Minnesota Center for Health Care Ethics and University of Minnesota Center for Bioethics released draft ethical pandemic guidelines on the rationing of scarce resources, where they estimated their were only enough PPE’s in the state of Minnesota to last 3 weeks into a severe pandemic.

This is perceived as being a big enough problem that six years ago we saw a report from NIOSH: Options To Maximize The Supply of Respirators During A Pandemic.Eleven years ago, in Caught With Our Masks Down, I wrote that the demand for PPEs during a serious pandemic would far exceed the available supply. At one time the HHS estimated the nation would need 30 billion masks (27 billion surgical, 5 Billion N95) to deal with a major pandemic (see Time Magazine A New Pandemic Fear: A Shortage of Surgical Masks).

The good news is we've been afforded more than a decade to prepare; to procure the basic PPEs needed protect our healthcare workers, first responders, and the general public.The bad news is, we instead spent billions on sexy, next-gen-high-tech pandemic `solutions' before first investing in the basic supplies and public health infrastructure we would need to deliver any of these solutions during a severe pandemic.

As a result, according to recent testimony in front of congress, we currently have about 1% of the number of PPEs we need for HCWs during a year-long severe pandemic. And, as we discussed often (see HCWs Willingness To Work During A Pandemic), a lack of PPEs is the greatest barrier to keeping healthcare workers healthy, and working during a pandemic.

That's not a temporary oversight, this is a long-standing institutional failure of the imagination of the highest order.The truth is, after the 2009 pandemic proved to be less severe than initially thought, pandemic preparedness went on the back burner - both here in the United States - and around the world. The prevailing attitude by the summer of 2010 was, we'd had our pandemic.

It wasn't so bad. And the next one probably won't come for another 40 years.Over the next couple of years most of the pandemic guidance created before 2009 was mothballed, the HHS's pandemic.gov website was taken down, and a thousand state, local, and business pandemic plans were locked away to gather dust in storage closets around the world.

In 2017, the CDC/HHS did release updated pandemic guidance (see HHS Pandemic Influenza Plan - 2017 Update & CDC/HHS Community Pandemic Mitigation Plan - 2017), and the World Health Organization released the results of a 2-year study WHO: Survey Of Pandemic Preparedness In Member States), which confirmed what we already knew.

The world was not ready for a pandemic.Just over half (n=104, or 54%) of member states actually responded to this survey. And of those, just 92 stated they had a national pandemic plan. Nearly half (48%) of those plans were created prior to the 2009 pandemic, and have not been updated since.

It gets worse, as only 40% of the responding countries have tested their pandemic preparedness plans - through simulated exercises - in the past 5 years.But, many nations had plans, we were told, to improve global pandemic preparedness. Hopefully, maybe in the next couple of years. While the United States, Canada, and the UK ranked among the best prepared nations in this (self-reported) survey, none of their scores were exactly stellar.

Regardless of the ultimate severity and impact of COVID-19, I've no doubt we will muddle through somehow. But because of our lack of foresight, preparedness, and a failure of our imagination, we'll take greater losses - both in terms of lives and suffering, and to our economy - than we needed to.

I expect, when it is over, that we'll be told that no one ever envisioned it could be as bad as it was, or could have foreseen the challenges we would face. But I think if you click any of the links embedded in this blog post, you'll know just how far from the truth that is.

The $64 question is whether we'll learn from this, and immediately begin to prepare for the next one. Or if we will we just go back to sleep, and hope the next one doesn't come on our watch.Because next time, Nature's laboratory may throw something at us far worse than COVID-19.