Kodiak Island - Credit Wikipedia

#17,170

For the second day running we have a report of the spillover of avian H5N1 to a new mammalian species (see yesterday's Canada Reports (Fatal) H5N1 Infection In A White-Sided Dolphin), this time detected in a brown bear cub in Alaska.

We've previously seen black bears infected - both in Canada (see First Detection Of H5N1 In A Black Bear) and in Alaska, but today's announcement is the first in a brown bear.

Foxes and seals have been the most commonly reported mammals to be infected by our current wave of HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b, but most animal deaths in the wild are never reported, and so our perception of H5N1's impact on non-avian wildlife is likely significantly under-estimated.

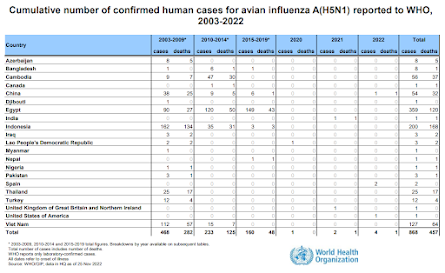

While only 4 human infections with this clade have been documented, all have resulted in extremely mild, or asymptomatic, illness. Other H5N1 clades have exacted a much greater toll.

In wildlife, which are likely exposed (via scavenging of infected dead birds) to much higher doses of the virus, more serious infections are common, often involving extrapulmonary spread and severe neurological manifestations.

The full text of the ADFG press release follows, which reports similar neurological impacts,. after which I'll return with a bit more.

Dec. 13, 2022 (Juneau) – Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI) has been detected in a brown bear cub on Kodiak Island, Alaska. This is the first time HPAI has ever been detected in a brown bear.A deer hunter on Kodiak found the dead bear, a cub of the year, on Nov. 26. Knowing the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) is conducting wildlife health surveillance, he collected the carcass and provided it to Nate Svoboda, the state Area Wildlife Biologist for Kodiak Island.Svoboda notified ADF&G wildlife veterinarian Dr. Kimberlee Beckmen. Beckmen investigated a similar case in October when the public reported a sick, stumbling black bear cub in Glacier Bay National Park. That bear also tested positive for HPAI.“We appreciate that the public and this hunter reported these animals,” Beckmen said. “We are dependent on help like this to understand the occurrence of wildlife diseases. Timely reporting and pictures really help.”An animal that is sick or freshly dead with no obvious injuries or a clear cause of death should be reported to Fish and Game (contact information follows). “Get the exact location, take pictures, and let us know so we can pick it up,” Beckmen said. “If you pick it up and turn it in, don’t handle it with bare hands – wear gloves or use a plastic bag.”Svoboda noted that there were no obvious wounds or clear signs indicating the cause of death, and that the cub looked emaciated. “That’s uncommon for this time of year when bears should be near their maximum weight prior to denning,” Svoboda said.He shipped the carcass to Anchorage for necropsy and further examination. Dr. Kathy BurekHuntington with Alaska Veterinary Pathology Services conducted a thorough exam and found indications of infection in the brain, lungs and liver. She sent samples to various laboratories to screen for pathogens including avian influenza. When the screening tests on nasal and rectal swabs, lung, and brain detected avian influenza, all samples were forwarded to the National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Iowa for confirmation and strain typing; NVSL determined it was Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza and the strain was the same H5N1 the black bear cub had.Microscopic examination of the tissues found that the bear died due to the viral infection causing inflammation and swelling in the brain, a meningoencephalitis, again the same as the black bear cub.The cubs were most likely exposed and infected while scavenging birds that died of the infection. “While mammals are at a lower risk of infection than poultry, scavenging an infected bird provides an opportunity to inhale a heavy dose of the virus while tearing into the tissues,” Beckmen said. “The cub was emaciated and that, in addition to being a very young animal, would make it more susceptible to succumbing to an infection. Fortunately, the virus is not transferred from bear-to-bear.”The Centers for Disease Control says this strain is low risk to people and is not a food-borne pathogen. However, proper hygiene is always advised when butchering wild animals for consumption. Wear gloves, wash hands and utensils with soap and water and disinfect surfaces. Cook meat to an internal temperature of 145⁰F degrees and poultry to 165⁰F to avoid risk of infections.Beckmen and State Veterinarian Dr. Robert Gerlach have also detected this virus in two other wild mammals during this outbreak, red foxes in Unalaska and in Unalakleet. Throughout the summer and fall HPAI was detected in eagles, ravens, shorebirds, waterfowl, and domestic poultry. Infection can occur when wild birds are attracted to places where domestic birds are fed.Domestic poultry is the main concern in Alaska and across the country. More than 53 million domestic poultry in 47 states have been affected by this outbreak and new detections are being found every week. Dr. Gerlach said his office in Anchorage is responding to an increased number of sick and dead birds in domestic poultry. It is apparent that the virus is continuing to circulate and impact the health of resident wild birds in Alaska even after migratory waterfowl have left the state. Cold and freezing weather conditions can preserve the virus for long periods of time.This means there will also be a continued threat to domestic bird populations (poultry and pet birds) and owners need to review and update their biosecurity measures. Do not feed poultry outside where it will attract wild birds, and cover outdoor pens. Bird and poultry owners should wash their hands and clean their boots prior to entering or handling their birds or other farms or pens where poultry exist.Sick or dead wildlife can be reported to the nearest ADF&G office or online via the link: https://www.adfg.alaska.gov/index.cfm?adfg=distressedwildlife.main .

Morbidity or mortality of domestic poultry can be reported to the Office of the State Veterinarian (907) 375-8215.

Since (with rare exceptions) we humans don't eat raw birds, we are unlikely to ingest the same quantities H5N1 viruses that bears, foxes, cats and other carnivores can in the wild (or, occasionally, in zoos), likely explaining our much milder infections with the virus.

But with every spillover event the virus is granted the opportunity to better adapt to mammalian hosts - and as we've seen in China, Indonesia, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Egypt - some H5N1 viruses can evolve to become deadly to humans.

So we watch avian flu's progress - and in particular, spillovers into mammals - with considerable interest, since abrupt changes in its behavior could indicate a change in its threat to human health.