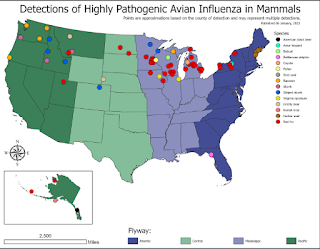

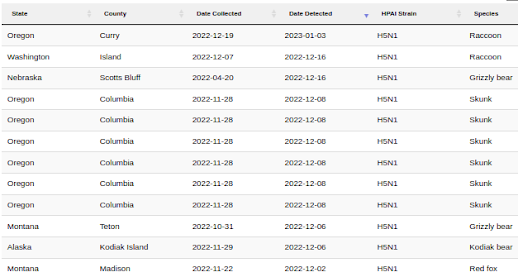

This raises the number of cases reported over the past year to 110, although this is expected to represent only a small fraction of the mammalian infections that have occurred over that time.

Most infected animals either recover - or die unnoticed in the wild - particularly in less accessible areas like the Everglades, bayous of Louisiana, or desert and mountainous regions out west. And some states are probably more proactive at recovering, and testing, dead animals than others.

Peridomestic mammals, like red foxes and skunks, are the most commonly reported terrestrial mammals infected. Being carnivorous scavengers - often living in close proximity to humans - makes it more likely that they are discovered.

And since some genotypes of H5N1 appear to be less pathogenic in mammals than others (see Preprint: Rapid Evolution of A(H5N1) Influenza Viruses After Intercontinental Spread to North America) some mammals may be infected, but recover, unnoticed in the wild.

This increased susceptibility of mammalian hosts of HPAI H5N1 is an obvious concern - particularly given the reports of severe illness and neurological manifestations - and the fact that 2 of the six known human infections with this clade have been severe (1 fatal).

The good news is, previous strains of HPAI H5N1 have never progressed beyond occasionally jumping from birds to humans, and human-to-human transmission has been exceedingly rare.

That said, the future evolution of these avian viruses is unknowable, and its failures to flourish in humans in the past is no guarantee of its future impact.

So we watch all novel virus spillovers into mammals with a healthy degree of suspicion.