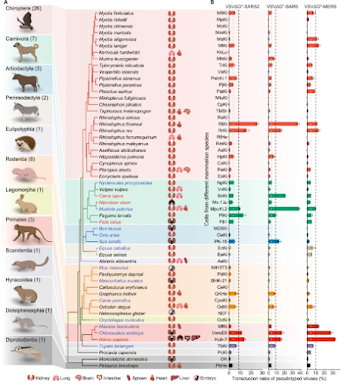

While overwhelmingly a `humanized' pathogen, SARS-CoV-2 has also found a plethora of other suitable hosts, including mink, deer, dogs, cats, and even rodents (see Nature: Comparative Susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV Across Mammals).

This co-circulation in non-human hosts could provide COVID with new opportunities to adapt and evolve, and potentially spill back into humans at a later date.

We saw an example of this kind of parallel evolution a month ago in Eurosurveillance: Cryptic SARS-CoV-2 Lineage Identified on Two Mink Farms In Poland, when we looked at the detection of two closely related COVID variants that turned up - 3 months apart - at two mink farms in Poland.Both closely matched a (pre-Omicron) variant (B.1.1.307) not seen in humans in nearly two years. At the same time both showed clear signs of continued evolution (at least 40 nt changes) since its last appearance in humans.

Between vaccines and acquired immunity, older variants have a limited shelf-life in humans and are supplanted by new variants fairly quickly. But they may be maintained in other animal populations, where they continue to evolve and adapt (see PNAS: White-Tailed Deer as a Wildlife Reservoir for Nearly Extinct SARS-CoV-2 Variants).

Over time, we've seen SARS-CoV-2 adapt to new species, including those that did not appear susceptible to the first wave of the pandemic (see PrePrint: The B1.351 and P.1 Variants Extend SARS-CoV-2 Host Range to Mice).

Early assurances that pigs, cattle, poultry, and other common livestock were not susceptible to COVID are constantly being reevaluated (see EID Journal: SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies Detected In Cattle Suggest Limited Spillover - Germany).

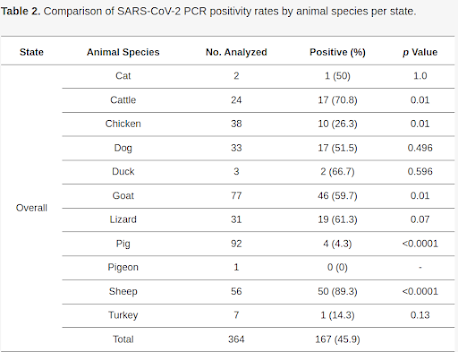

In fact the number is so high, my first inclination was to suspect cross-contamination. While the authors address this concern, they believe their methods were sound.

Animals tested came primarily from in and around small family farms in rural Nigeria, where the human-animal interface is much closer than with large commercial farms. Surprisingly, they found evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in poultry, cattle, goats, and even lizards.

Due to its length I've only posted the link, abstract, and a few excerpts. You'll want to read the study in its entirety. I'll have a bit more when you return.

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Terrestrial Animals in Southern Nigeria: Potential Cases of Reverse Zoonosis

by

Anise N. Happi1,*, Akeemat O. Ayinla1, Olusola A. Ogunsanya 1, Ayotunde E. Sijuwola 1, Femi M. Saibu 1, Kazeem Akano 1,2, Uwem E. George 1,2, Adebayo E. Sopeju 1, Peter M. Rabinowitz 3, Kayode K. Ojo 4, Lynn K. Barrett 4, Wesley C. Van Voorhis 4 and Christian T. Happi 1,2

Abstract

Since SARS-CoV-2 caused the COVID-19 pandemic, records have suggested the occurrence of reverse zoonosis of pets and farm animals in contact with SARS-CoV-2-positive humans in the Occident. However, there is little information on the spread of the virus among animals in contact with humans in Africa. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the occurrence of SARS-CoV-2 in various animals in Nigeria.

Overall, 791 animals from Ebonyi, Ogun, Ondo, and Oyo States, Nigeria were screened for SARS-CoV-2 using RT-qPCR (n = 364) and IgG ELISA (n = 654). SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates were 45.9% (RT-qPCR) and 1.4% (ELISA). SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in almost all animal taxa and sampling locations except Oyo State. SARS-CoV-2 IgGs were detected only in goats from Ebonyi and pigs from Ogun States.Overall, SARS-CoV-2 infectivity rates were higher in 2021 than in 2022. Our study highlights the ability of the virus to infect various animals. It presents the first report of natural SARS-CoV-2 infection in poultry, pigs, domestic ruminants, and lizards. The close human–animal interactions in these settings suggest ongoing reverse zoonosis, highlighting the role of behavioral factors of transmission and the potential for SARS-CoV-2 to spread among animals. These underscore the importance of continuous monitoring to detect and intervene in any eventual upsurge.

(SNIP)

Cases of natural SARS-CoV-2 infection have been reported in dogs and cats, but to the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of SARS-CoV-2 natural infection in poultry, pigs, and lizards. The relatively high PCR positivity rate in some animal species in our study may have been driven by horizontal transmission between these animals, especially in those intensively reared. This is not surprising as once a pathogen crosses from an animal to a human, it is likely going to cross from one animal type to another animal taxa. Importantly, different studies have identified direct contact as the most efficient route for animal-animal SARS-CoV-2 transmission [41,50].

We acknowledge that our study has some limitations. The protocol and kits used to carry out RT-qPCR were designed for human subjects. However, the results were interpreted using the Ct values which correspond to the N-gene which are specific for SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, the cross-sectional design of our study limits our investigation of the cause–effect relationships between the animal cases and human cases. However, all animals sampled were found living close to humans. Finally, at the time this study was carried out, we had access to secondary antibodies (IgG) for only five animal species. This hindered our ability to screen for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in other species.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated evidence of natural infection with SARS-CoV-2 in a wide range of animal species existing in close contact with humans with the use of molecular and serological analyses. The degree of SARS-CoV-2 detection in animals was greater in 2021 than in 2022, correlating with a decrease in human infection rates over the same period. The proximity between humans and animals in this setting as well as the temporal correlation of positivity rates strongly suggest a human–animal transmission. However, there is a need for further research into the role of SARS-CoV-2-positive animals in the maintenance of the virus and transmission to humans and among animals. Continuous monitoring of the virus in animals and humans is recommended for preparedness in case of mutations that may increase the virulence and transmissibility of the virus as its moves from species to species.

While governments and health agencies have declared the COVID emergency to be over, SARS-CoV-2 will continue to do what viruses have done successfully for millions of years; evolve, adapt, and expand their host range.

Which means the possibility exists that a radically different variant could emerge from a non-human host for which we have little or no immunity.

All of which makes the continued surveillance of companion animals, farmed animals, and wildlife for new COVID variants a wise investment.