#17,493

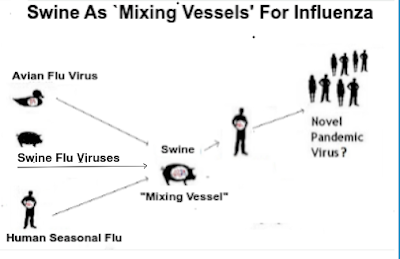

While our attention is currently drawn towards avian H5 influenza, pigs play an important role in the ecology and evolution of many types of Influenza A viruses, as they are susceptible to swine, human, and avian strains.

Swine are one of the most commonly raised food animals in the world, accounting for somewhere between 700 million and 800 million head at any given time. Swine surveillance, and testing for swine flu viruses, however, is limited - even in places like the United States - and nonexistent in much of the world.influenza's superpower is its ability to evolve, and adapt to new hosts. If - under the right conditions - these viruses are able to reassort (see graphic above ), they may produce new and potentially more dangerous subtypes or genotypes.

The swine virus had acquired a gene from the pandemic H1N1 virus via genetic reassortment. Since then, Hong Kong has increased their surveillance of pigs – particularly those imported from the mainland – by regularly taking routine samples at a local slaughterhouse.

But most of what happens in swine herds around the world goes unmonitored. Occasionally we'll see a report of a swine-variant spillover infection (in a human), or a swine influenza study (see below), but mostly, we are flying blind.

Study: Seroconversion of a Swine Herd in a Free-Range Rural Multi-Species Farm against HPAI H5N1 2.3.4.4b Clade Virus

Viruses: Swine-to-Ferret Transmission of Antigenically Drifted Contemporary Swine H3N2 Influenza A Viruses

All of which brings us to a new report, published this week in the CDC's EID Journal, on swine influenza surveillance conducted at a slaughterhouse in Hanoi, Vietnam, which received pigs from roughly 2 dozen provinces.

This surveillance (conducted between 2013 and 2019) found repeated introductions of both human and swine influenza viruses into the herds, and documents the detection of a new H1-δ1a strain which may have increased zoonotic potential.

First some excerpts from the report, after which I'll have a brief postscript.

Research

Long-term Epidemiology and Evolution of Swine Influenza Viruses, Vietnam

Jonathan Cheung, Anh Ngoc Bui, Sonia Younas, Kimberly M. Edwards, Huy Quang Nguyen, Ngoc Thi Pham, Vuong Nghia Bui, Malik Peiris1, and Vijaykrishna Dhanasekaran1

Abstract

Influenza A viruses are a One Health threat because they can spill over between host populations, including among humans, swine, and birds. Surveillance of swine influenza virus in Hanoi, Vietnam, during 2013–2019 revealed gene pool enrichment from imported swine from Asia and North America and showed long-term maintenance, persistence, and reassortment of virus lineages. Genome sequencing showed continuous enrichment of H1 and H3 diversity through repeat introduction of human virus variants and swine influenza viruses endemic in other countries.

In particular, the North American H1-δ1a strain, which has a triple-reassortant backbone that potentially results in increased human adaptation, emerged as a virus that could pose a zoonotic threat. Co-circulation of H1-δ1a viruses with other swine influenza virus genotypes raises concerns for both human and animal health.

(SNIP)

Discussion

Our study, conducted during 2016–2019, provides insights into the evolution and epidemiology of swIV in Vietnam, a major pork-producing country in Asia. Through longitudinal surveillance at a central slaughterhouse in Hanoi, which sourced pigs from across the country, we found H1N1, H1N2, and H3N2 swIVs co-circulating. This finding is consistent with surveillance conducted in 2013–2014 (13,26) and with other studies in Vietnam (23,27,28), indicating that the swIV subtypes circulating in Vietnam are similar to those found across Asia and globally (31–34).

We found that the genetic diversity of swIV in Vietnam since 2010 is attributable to the persistence of several swine-origin H1N2 and H3N2 viruses, first reported in other countries in Asia and North America and likely imported via swine trade. We also identified repeat introductions of human pH1N1 viruses through reverse zoonosis. We found extensive reassortment of major swIV lineages, including H1N2 and H3N2 frequently acquiring pH1N1 internal genes and only rare acquisition of other swIV internal genes by pH1N1 lineage viruses. As a result, most recent swIVs from Vietnam contain pH1N1 internal genes. However, 2 divergent H1-δ virus lineages (originally derived from pre-2009 seasonal H1N1 viruses), detected in our most recent sample from 2019, maintained the TR lineage NA and internal genes (genotypes 10, 12, and 20) (Figure 3, panel B).

Although repeated introductions of pH1N1 into swine is consistent with previous swine surveillance from Vietnam (13) and southern China (35,36), the frequency of detections of new human pH1N1 virus lineages in swine in Vietnam has tapered off since 2015. Although onward transmission of pH1N1 was not sustained for most introductions, 1 lineage, first detected in northern Vietnam during 2013–2014 (13), persisted in swine for >4 years and reassorted with other prevailing swIV lineages. When introduced as components of reassortants, pH1N1-origin gene segments tend to be maintained in pigs (27), whereas viruses whose genomes are entirely derived from pH1N1 tend not to be sustained in the pig population. This phenomenon has been observed globally and in southern China and Hong Kong surveillance studies, which showed that viruses from purely pH1N1 failed to sustain the pig population after each introduction (36). Similar evidence of pH1N1 being maintained within swine populations has been reported from the United States (37) and Australia (38).

Pre-2009 seasonal H1N1 influenza-derived swine viruses (classified under H1-δ) are potentially gaining predominance in swine in Vietnam. Of note, an H1N2 H1-δ1a virus lineage with limited cross-reactivity to other H1 swIV lineages was detected in 2019, and serosurveillance showed evidence of circulation since March 2016. The increasing prevalence of H1-δ–like lineages increases the risk for zoonotic transmission. Previous studies demonstrated significant antigenic distance between pH1N1-like viruses and H1-δ cluster viruses (H1-δ–like and H1-δ1-a) (29,30), and current seasonal influenza vaccines do not elicit protection against H1-δ–like swIVs (39–41). It is therefore important to ascertain whether current diagnostics can distinguish pre-2009 H1 viruses from currently circulating human seasonal H1 strains.

H1-δ1a viruses likely entered Vietnam via imported swine, demonstrating the role of trade in the global dissemination of swIVs (42). East and Southeast Asia countries, including China, Thailand, and Vietnam, which produce >50% of pork globally, are hotspots for emerging infectious diseases from swine (43,44). Vietnam ranks second in Asia for pork production, producing 19.62 million heads in 2019 (45). In addition, pork consumption in Vietnam has risen rapidly, from 12.8 kg/head/year in 2001 to 31.4 kg/head/year in 2018 (46), mostly in the form of fresh pork. Vietnam has also been importing breeding hogs from the United States since 1996. On average, 553 breeding hogs were imported each year from the United States during the 2010s, with a peak in 2014–2015 (Appendix 2 Figure 2) (47). The H1-δ1a lineage may have been introduced to Vietnam by imported breeding hogs in early 2016, as was seen in mainland China in the early 1990s (48).

In each of the swIV lineages detected in Vietnam, we discovered evidence of localized circulation, as evidenced by periods of unsampled diversity and long phylogenetic branches, likely at the provincial level. Despite the limited mixing of swine populations in Vietnam before slaughter (44), the infrequent detection of persistent lineages in the central slaughterhouse suggests that the genetic diversity of swIV in Vietnam may be high. This diversity is likely driven by factors such as livestock density and turnover. In comparison, swine in the United States are exposed to a greater degree of mixing during their lifespan because they are transported across long distances for feeding and fattening, which results in replacement by advantageous swIV lineages (37).

Our findings indicate that the swIV gene pool in Vietnam is continually enriched by importations from North America and from other countries in Asia. Those viruses include a novel cluster of H1-δ1a (genotype 10) viruses, which may pose a zoonotic threat (49). As the H1-δ1a virus was found only during the last sample collection, its persistence is uncertain. Recurrent transmission of pH1N1 viruses from humans to swine and reassortment with other swIV lineages have increased genetic diversity. Hence, to limit further introductions and diversification of the swIV gene pool in Vietnam, it is important to actively monitor both local swine herds and imported swine.

Dr. Cheung is a researcher at the University of Hong Kong School of Public Health. His research interests are the molecular evolutionary virology and epidemiology of zoonotic influenza viruses.

H1N2 variant [A/California/62/2018] Jul 2019 5.8 5.7 ModerateH3N2 variant [A/Ohio/13/2017] Jul 2019 6.6 5.8 Moderate

H3N2 variant [A/Indiana/08/2011] Dec 2012 6.0 4.5 Moderate

In 2021 the CDC ranked a Chinese Swine-variant EA H1N1 `G4' as having the highest pandemic potential of any flu virus on their list (see EID Journal: Zoonotic Threat of G4 Genotype Eurasian Avian-Like Swine Influenza A(H1N1) Viruses, China, 2020).

So far, the good news is that currently circulating swine variant viruses haven't become biologically `fit' enough spark a pandemic. In order to be successful, they need to be able to replicate and transmit on par with already circulating human flu viruses.