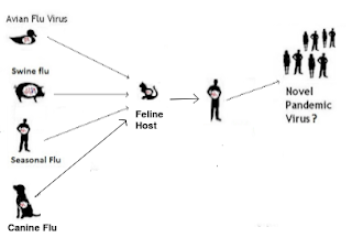

Cats As Potential Vectors/Mixing Vessels for Novel Flu

#18,603

Since the first of the year the USDA has added 21 cats to their list of mammals with H5N1, although it is generally assumed that this is just a fraction of the actual number of cases. Since last March, they have confirmed 85 domestic cats with the virus.

In several cases, we've seen reports of multiple cat deaths in a household, but only one or two were actually tested (and counted). In other cases, cats may die unobserved in the wild - or are never tested for the virus - while others may experience mild illness and recover.

Since the emergence of a new, more mammalian-adapted H5N1 virus in 2021, we've seen a number of outbreaks in cats around the world (see reports from Poland & South Korea). In those outbreaks, as well as several recent cases in California and Oregon, the consumption of raw meat and/or milk was the likely exposure.

Yesterday San Mateo County, California reported HPAI H5 in a stray cat taken in by a household, and warned residents to contact their veterinarian - and monitor their own health - if their pet develops symptoms.

Overnight there was a related report in the NYTs (see C.D.C. Posts, Then Deletes, Data on Bird Flu Spread Between Cats and People). I didn't get to see that data, and can offer no additional insight beyond a review - after the break - of some recent papers on avian flu in companion animals.

February 6, 2025

Redwood City — State veterinary and health officials have confirmed a case of H5N1 (bird flu) in a domestic stray cat in San Mateo County. The infection, which is not related to the recent instance of bird flu in a backyard flock, was found in a stray cat in Half Moon Bay that had been taken in by a family. When it showed symptoms, they took it to Peninsula Humane Society, whose veterinarians examined it and requested testing. Lab results confirmed H5N1. It is not known how the cat was infected and it was euthanized due to its condition.

Cats may be exposed to bird flu by consuming infected bird, being in environments contaminated with the virus and consuming unpasteurized milk from infected cows or raw food. Inside domestic animals, such as cats and dogs, that go outside are also at risk of infection.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the risk of cats spreading H5N1 to people is extremely low, though it is possible for cats to spread some strains of bird flu to people.

While there are no human cases of H5N1 related to this case, this detection in a cat highlights the importance of being proactive about preventing the spread of the virus.

Residents whose pets show signs of illness should contact their veterinarian.

Pets infected with H5N1 may experience a loss of appetite, lethargy and fever, along with neurologic signs, including circling, tremors, seizures or blindness. The illness may quickly progress to:

- Severe depression

- Discharge from eyes or nose

- Other respiratory signs, such as rapid shallow breathing, difficulty breathing and sneezing or coughing

- Pets with severe illness may die.

If a pet is showing signs of illness consistent with bird flu and has been exposed to infected (sick or dead) wild birds or poultry, residents should contact a veterinarian and monitor their own health for signs of fever or infection.

“We all want to make sure our companion animals are healthy and safe from disease,” said Lori Morton-Feazell, San Mateo County’s chief of Animal Control and Licensing. “If your pet is sick, your veterinarian can determine whether it should be tested for bird flu or any other virus or disease.”

We've known for 2 decades that cats are susceptible to HPAI H5 infection, after hundreds of large cats (lions and tigers) kept in zoos across South East Asia died from eating infected raw chicken; a tragedy we've seen repeated often, including in Vietnam last fall.

A decade ago, in HPAI H5: Catch As Cats Can, we looked at the sporadic spillovers into felines, and in 2023 we reviewed A Brief History Of Avian Influenza In Cats, which included the outbreak of H7N2 in shelter cats in NYC, and the infection of at least two workers.

Two months ago, in Emerg. Microbes & Inf.: Marked Neurotropism and Potential Adaptation of H5N1 Clade 2.3.4.4.b Virus in Naturally Infected Domestic Cats, we looked at a report on the HPAI H5 infection of a house full of domestic cats (n=8) in South Dakota last April.

Isolates from the two cats that were tested showed signs of viral adaptation to a mammalian host. The authors wrote:

Cat H5N1 genomes had unique mutations, including T143A in haemagglutinin, known to affect infectivity and immune evasion, and two novel mutations in PA protein (F314L, L342Q) that may affect polymerase activity and virulence, suggesting potential virus adaptation.

Dead cats showed systemic infection with lesions and viral antigens in multiple organs. Higher viral RNA and antigen in the brain indicated pronounced neurotropism.

Last November, in Eurosurveillance: (HPAI) H5 virus Exposure in Domestic & Rural Stray Cats, the Netherlands, October 2020 to June 2023, we looked at a study which found:

Of the 701 stray cats sampled, 83 had been exposed to HPAI virus, whereas only four of the 871 domestic cats. Exposure was more common in older cats and cats living in nature reserves. Some stray cats had been exposed to both avian and human influenza viruses. In contrast, 40 domestic cats were exposed to human influenza viruses.

Curiously, while we've seen no reports of HPAI H5 in European dairy cows, the authors reported finding the `. . . highest HPAI H5 seropositivity was found in cats living in nature reserves (37.8%) and on dairy farms (11.0%).'

While the CDC continues to rank the risk to general public from avian flu as low, they do provide very specific guidance to pet owners on how to limit their risk of infection from the virus (see What Causes Bird Flu in Pets and Other Animals).

We are currently getting far less information on avian flu - both here in the United States, and from many countries around the world - than we'd like. This is a trend which gained steam during the COVID pandemic, and has grown increasingly worse over time (see Flying Blind In The Viral Storm).

While I don't profess to understand the rationale behind these policy decisions, I do know that any short-term economic or political advantages to be had from them will pale compared to the damage we'll see should another pandemic virus emerge.

And as history tells us, sooner or later, another one will.