Cats As Potential Vectors/Mixing Vessels for Novel Flu

#18, 713

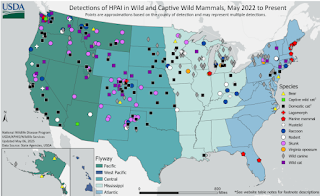

Not quite a year ago the USDA added domestic cats (n=16) to their HPAI H5N1 in mammalian wildlife list, many of which were reportedly barn cats exposed to infected dairy cows.

We'd seen scattered reports of domestic cats infected with H5N1 before - both in the United States (see here & here), and in many other countries (see Poland, South Korea, and France) - but these spillover events are undoubtedly under-reported

A year later the USDA now lists 138 domestic cats, 37 lions, 6 tigers, 15 bobcats, 2 Lynx, & 2 others positive for H5N1. Felines now comprise > 30% of all of the mammals on their list.

Although we've known cats were susceptible to H5N1 for more than 20 years (see 2015's HPAI H5: Catch As Cats Can), recent changes to the clade 2.3.4.4b H5 virus have turned a relatively rare event into a more common one (see 2023's A Brief History Of Avian Influenza In Cats).

While cat-to-human transmission of H5N1 has yet to be confirmed, in late 2016 we saw an avian H7N2 virus sweep through hundreds of cats housed at multiple New York City Animal shelters - while also infecting at least two people - showing that that cats can become efficient transmitters of a novel avian flu virus as well.

A year ago we looked at a Preprint: Avian Influenza Virus Infections in Felines: A Systematic Review of Two Decades of Literature, which cited:

(excerpt)Through our systematic review, we identified 486 avian influenza virus infections in felines, including 249 associated feline deaths, reported in the English scientific literature from 2004 – 2024. The reports represent cases from 7 geographical regions, including 17 countries and 12 felid species.

Of particular interest are domestic cats infected with H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4, which represents a variant in the hemagglutinin serotype 5 gene of IAV which became the dominant IAV H5 serotype among poultry in 2020 [35]. Clade 2.3.4.4b was first reported in felines in 2022, and among the feline infections reported, it has yielded a mortality rate of 67%.

Since then, the authors have gathered more data leading to a revised (and now peer-reviewed) version being published this past week in OFID (Open Forum Infectious Diseases). First, a link and some excerpts, followed by some snippets from a University of Maryland press release.

I'll have a postscript (and a little house keeping) after the break.

Avian Influenza Virus Infections in Felines: A Systematic Review of Two Decades of Literature

Kristen K Coleman , Ian G Bemis

Open Forum Infectious Diseases, https://doi.org/10.1093/ofid/ofaf261

Published: 07 May 2025 Article history

Abstract

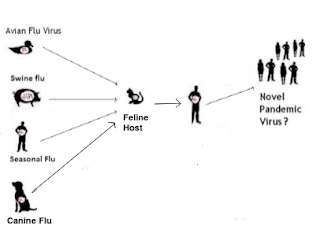

As an avian influenza virus (AIV) panzootic is underway, the threat of a human pandemic is emerging. Infections among mammalian species in frequent contact with humans should be closely monitored. One mammalian family, the Felidae, is of particular concern. Domestic cats are susceptible to AIV infection and provide a potential pathway for zoonotic spillover to humans. Here, we provide a systematic review of the scientific literature to describe the epidemiology and global distribution of AIV infections in felines reported from 2004–2024.

We identified 607 AIV infections in felines, including 302 associated deaths, comprising 18 countries and 12 felid species. We observed a drastic flux in the number of AIV infections among domestic cats in 2023 and 2024, commensurate with the emergence of H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b. We estimate that this phenomenon is underreported in the scientific literature and argue that increased surveillance among domestic cats is urgently needed.

(SNIP)

Based on the avian influenza seropositivity of various felines in some of the studies we reviewed, we estimate that feline cases are markedly underreported in the literature.

Additionally, testing feline patients for AIV is not a routine practice as treatment options are limited under most circumstances. While it is often required that cases of HPAI shall be reported to public health authorities, subtype and clade is often not confirmed. As a result, several publications do not report the AIV subtype or clade. However, recent and ongoing outbreaks of H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b among dairy cattle in the U.S., representing a significant threat to farm cats [2], has prompted multiple states to begin post-mortem H5N1 testing among rabies-negative domestic cats.However, subclinical infections of H5N1 in domestic cats do occur [3], including asymptomatic infections of clade 2.3.4.4b [4]. Thus, we argue that wider surveillance among domestic cats is urgently needed to determine how widespread the virus is in order to appropriately assess the risk of spillover to humans and other animals.

As feline-to-human transmission of AIV has been documented [7–9], and potential airborne and fomite-mediated transmission implicated [42], farm and free-roaming cat owners, veterinarians, zoo keepers, and animal shelter volunteers may have a heightened risk of AIV infection during epizootics among birds and mammals.

Bird flu study points to risk of another pandemic

First major global review of bird flu in cats shows an emerging threat of a human pandemic

University of Maryland

Credit: UMD

COLLEGE PARK, Md. — It’s spring, the birds are migrating and bird flu (H5N1) is rapidly evolving into the possibility of a human pandemic. On May 7, researchers from the University of Maryland School of Public Health published a major study in Open Forum Infectious Diseases documenting research on bird flu in cats and calling for urgent surveillance of cats to help avoid human-to-human transmission.

“The virus has evolved, and the way that it jumps between species – from birds to cats, and now between cows and cats, cats and humans – is very concerning. As summer approaches, we are anticipating cases on farms and in the wild to rise again,” says lead and senior author Dr. Kristen Coleman, assistant professor in UMD School of Public Health’s Department of Global, Environmental and Occupational Health and affiliate professor in UMD’s Department of Veterinary Medicine.

While the CDC continues to rank the risk to general public from avian flu as low, they do provide very specific guidance to pet owners on how to limit their risk of infection from the virus.

Bird Flu in Pets and Other Animals

Key points

- Avian influenza viruses, which can cause bird flu illness, mainly infect and spread among wild birds and domestic poultry. However, some avian influenza viruses can infect and spread to other animals, including pets.

- While it is unlikely that you would get sick with bird flu from direct contact with your infected pet, it is possible.

- If your pets (including pet birds, cats or dogs) go outside and eat or are exposed to sick or dead birds, dairy cows, or other animals infected with avian influenza viruses, they could become infected.

- Prevent pets from interacting with wild birds, backyard poultry, cows, or other outdoor animals.

- Keep pets away from clothes, surfaces or environments that could potentially be contaminated with avian influenza viruses.

- Do not feed pets raw pet food or unpasteurized (raw) milk.

Prevention measures for people

- As a general precaution, people should avoid direct contact with wild birds and observe wild birds only from a distance.

- Pet owners should prevent their pets (including pet birds, dogs, and cats) from interacting with potentially infected dairy cows, backyard flocks, and wild animals.

- Pet owners should not let their pets consume raw pet food or raw (unpasteurized) milk.

- Pet owners should prevent their pets from touching clothes or other surfaces or environments that could potentially be contaminated with avian influenza viruses.

- Do not touch sick or dead birds, their feces, litter, or any surface or water source (ponds, waterers, buckets, pans, troughs) that might be contaminated with their saliva, feces, or any other bodily fluids without wearing PPE.