#16,615

Yesterday (Friday Mar. 4th) the USDA reported the 10th state to detect HPAI H5 in either commercial or backyard poultry (see USDA Confirms Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza in a Flock of Commercial Broiler Chickens in Missouri), joining Connecticut and Iowa who also reported (backyard flock) infections this week.

Reported losses so far in 2022 (from the virus, and from culling) are roughly 1.8 million birds.

Additionally, 19 states have reported HPAI in wild birds (see USDA list). As winter recedes and migratory birds begin their yearly trek to their northern summer roosting areas, they may spread the virus even further west (see migratory flyway map below).

Unlike the highly virulent and often deadly HPAI H5N6 virus we've been following in China (see HK Monitoring 4 More H5N6 Cases On the Mainland), the Eurasian HPAI H5N1 (clade 2.3.4.4b) virus poses only a small risk to human health.

Of the handful of infections we know of (in Russia, Nigeria and the UK), all have been mild or asymptomatic.

That said, all viruses continue to mutate and evolve, and we've seen some evidence to suggest that this Eurasian H5N1 (and related H5Nx viruses) may be moving towards becoming a more `mammalian adapted' subtype. Some recent blogs include:

Netherlands DWHC Reports another Mammal (Polecat) Infected With H5N1

Netherlands: WBVR Diagnoses Avian H5N1 In Another Fox

EID Journal: HPAI A(H5N1) Virus in Wild Red Foxes, the Netherlands, 2021

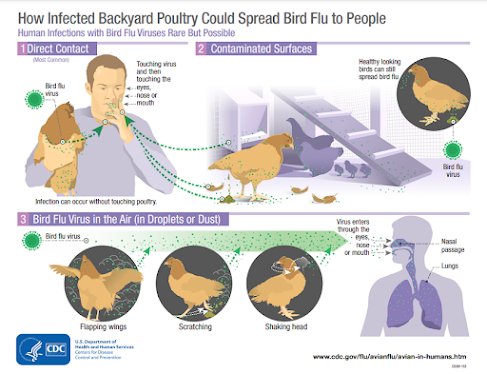

While the risk of human infection from our current H5N1 epizootic is low, it is not zero, particularly for those who have close, direct, or extended contact with poultry or wild birds. Just as those who raise pigs are exposed to swine variant viruses, poultry farmers may be exposed to avian flu viruses.

While HPAI H5 is primarily a concern to poultry interests, public health officials also know that human infections are always possible and have increased not only their readiness, but their messaging to the public in recent weeks (see below)

Avian Influenza Current Situation SummaryRecent Bird Flu Infections in U.S. Wild Birds and Poultry Pose a Low Risk to the Public

With the number of outbreaks in poultry increasing, so does the risk of seeing a human infection. The CDC's latest update (below) indicates that 140 people with a high risk exposure are under surveillance (none are reported infected), and in this installment, the CDC discusses What Might Happen if human infections are detected.

March 4, 2022 Update: H5N1 Bird Flu Poses Low Risk to the Public

More information about current H5N1 viruses

March 4, 2022—To date, highly pathogenic avian influenza A(H5N1) viruses (“H5N1 bird flu viruses”) have been detected in U.S. wild birds in 13 states and in commercial and backyard poultry in 10 states , according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Animal and Plant Health Inspective Service (APHIS). Based on available epidemiologic and virologic information about these viruses, CDC believes that the risk to the general public’s health from current H5N1 bird flu viruses is low, however some people may have job-related or recreational exposures to birds that put them at higher risk of infection. CDC is watching this situation closely and taking routine preparedness and prevention measures in case this virus changes to pose a greater human health risk.

Right now, the H5N1 bird flu situation is primarily an animal health issue. The U.S. Department of Interior and USDA APHIS are the lead federal agencies for this situation. They are respectively responsible for outbreak investigation and control of bird flu in wild birds and in domestic birds (poultry). USDA has publicly posted the genetic sequences of several of the recently detected U.S. H5N1 bird flu viruses. These viruses are from clade 2.3.4.4b* pdf icon[333 KB, 11 Pages] which is the most common H5N1 bird flu virus worldwide at this time. Comparing information about these newer viruses to previously circulating H5N1 bird flu viruses helps inform the human health risk assessment.(SNIP)What is CDC Doing?

Because flu viruses are constantly changing, CDC will continue to monitor these viruses to look for genetic or epidemiologic changes suggesting they might spread more easily to and between people, and cause serious illness in people, or for changes that suggest reduced susceptibility to antivirals, as well as changes in the virus that might mean a new CVV should be developed.

CDC is working with USDA and state public health partners to monitor for potential infections in exposed persons in the states where H5N1 bird flu virus detections have occurred. If human infections with H5N1 bird flu virus are identified, CDC will help with surveillance, contact tracing, and other steps to monitor for and reduce spread in affected jurisdictions. At this time, more than 140 people in the U.S. who have had H5N1 exposures with infected birds/poultry have been or are being monitored for symptoms and no cases of H5N1 infection have been found.

CDC is conducting additional laboratory work to further characterize current H5N1 bird flu viruses.

CDC is providing guidance including recommendations for personal protective equipment and information for people exposed to birds infected with avian influenza viruses and guidance for testing and treatment. A review of these guidance documents for any needed updates is ongoing.

What Might Happen

Given past human infections with bird flu viruses resulting from close contact with infected birds/poultry, sporadic human infections with current H5N1 bird flu viruses would not be surprising, especially among people with exposures who may not be taking recommended precautions (like wearing personal protective equipment, for example).

Sporadic infections like that would not change CDC’s risk assessment. However, identification of multiple instances of H5N1 bird flu viruses spreading from birds to people, or of changes in the virus associated with adaptation to mammals, would raise CDC’s risk assessment.

These changes could indicate the virus is adapting to spread more readily from birds to people. If limited, non-sustained human-to-human spread with this virus were to occur, that also would raise the public health threat because it could mean the virus is adapting to spread better between people. Note that sustained human-to-human spread is needed for a pandemic to occur.

What To Do

As a general precaution, people should avoid direct contact with wild birds and observe them only from a distance, if possible. Wild birds can be infected with bird flu viruses without appearing sick. If possible, avoid contact with poultry that appear ill or have died. Avoid contact with surfaces that appear to be contaminated with feces from wild or domestic birds, if possible. CDC has information about precautions to take with wild birds. CDC also has guidance for specific groups of people with exposure to poultry, including poultry workers and people responding to poultry outbreaks.

If you must handle wild birds or sick or dead poultry, minimize direct contact by wearing gloves and wash your hands with soap and water after touching birds. If available, wear respiratory protection such as a medical facemask. Change your clothing before contact with healthy domestic poultry and birds after handling wild birds, and discard the gloves and facemask, and then wash your hands with soap and water. Additional information is available at Information for People Exposed to Birds Infected with Avian Influenza Viruses of Public Health Concern. As a reminder, it is safe to eat properly handled and cooked poultry and poultry products in the United States. The proper handling and cooking of poultry and eggs to an internal temperature of 165˚F kills bacteria and viruses, including H5N1 bird flu viruses.

And admittedly, an H5 pandemic may never happen (see Are Influenza Pandemic Viruses Members Of An Exclusive Club?).

Regardless of what causes it, another pandemic is inevitable. It's just a matter of time.