#17,149

While once greatly feared and the cause of numerous epidemics, Scarlet Fever - caused by a bacteria called group A Streptococcus – can be today successfully treated by modern antibiotics and is usually a mild disease.

The illness is caused by the same bacteria that causes `strep throat’, and is characterized by fever, a very sore throat, a whitish coating or sometimes `strawberry’ tongue, and a `scarlet rash’ that first appears on the neck and chest.

Scarlet fever primarily affects children under the age of 10, as adults generally develop immunity as they grow older. Untreated, infection can occasionally lead to serious illness, and even death.

Far less common, albeit considerably more serious, is a related illness called iGAS (invasive Group A Strep), which indicates infection of the bloodstream, deep tissues, or lungs, and may result in severe (and frequently fatal) cases of necrotizing fasciitis and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

While children may be affected, iGAS most commonly occurs in older adults. In 2019 we followed an unusual outbreak in Essex, UK which as of this 2020 update had totaled 39 cases, 33 which were confirmed as part of this outbreak and six which were probable cases, and 15 deaths.

Strains are identified by changes in their M-protein gene sequence (emm types) – which often determines virulence - and within these types new variants can emerge.The Essex outbreak was identified as emm44.

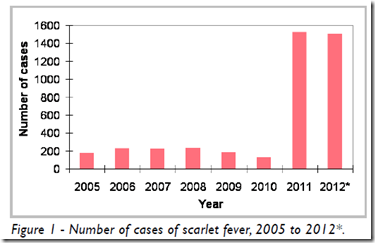

In 2011 and 2012 we followed an unusual erythromycin resistant (but still sensitive to Penicillin & other 1st generation cephalosporins) scarlet fever outbreak in Hong Kong (see Hong Kong: Scarlet Fever In 2012), which caused a dramatic increase in cases (see chart below), and resulted in a small number of pediatric fatalities.

In 2015 a Nature Genetics journal article attributed Hong Kong’s severe outbreak to the emergence of a new emm12 variant (see Emergence of scarlet fever Streptococcus pyogenes emm12 clones in Hong Kong is associated with toxin acquisition and multidrug resistance).

In the middle of the last decade the UK saw a sharp rise in scarlet fever cases as well (see 2018's UK: `Exceptional' Scarlet Fever Season Continue), which according to a 2019 study in the Lancet (see

Emergence of Dominant Toxigenic M1T1 Streptococcus pyogenes Clone in England) was driven by the emergence of new emm variants.

As we've seen with influenza, RSV, and other respiratory illnesses, the number of scarlet fever cases reported over the first two years of the pandemic plummeted, likely due to social distancing and increased precautions taken against COVID.

And just as we are seeing robust, and unseasonable, outbreaks of flu and RSV, the UK is reporting a sharp rise in scarlet fever and iGAS cases (see chart below) this fall, which sadly have resulted in 6 recent pediatric deaths.

We've excerpt from two UKHSA reports. First, this press release, then we'll look at the UK's weekly surveillance data.

The latest data from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) shows that scarlet fever cases continue to remain higher than we would typically see at this time of year.

From:UK Health Security Agency

Published 2 December 2022

There were 851 cases reported in week 46, compared to an average of 186 for the preceding years.

Scarlet fever is usually a mild illness, but it is highly infectious. Therefore, look out for symptoms in your child, which include a sore throat, headache, and fever, along with a fine, pinkish or red body rash with a sandpapery feel. On darker skin, the rash can be more difficult to detect visually but will have a sandpapery feel. Contact NHS 111 or your GP if you suspect your child has scarlet fever, because early treatment of scarlet fever with antibiotics is important to reduce the risk of complications such as pneumonia or a bloodstream infection. If your child has scarlet fever, keep them at home until at least 24 hours after the start of antibiotic treatment to avoid spreading the infection to others.

Scarlet fever is caused by bacteria called group A streptococci. These bacteria also cause other respiratory and skin infections such as strep throat and impetigo.

In very rare occasions, the bacteria can get into the bloodstream and cause an illness called invasive Group A strep (iGAS). While still uncommon, there has been an increase in invasive Group A strep cases this year, particularly in children under 10. There were 2.3 cases per 100,000 children aged 1 to 4 compared to an average of 0.5 in the pre-pandemic seasons (2017 to 2019) and 1.1 cases per 100,000 children aged 5 to 9 compared to the pre-pandemic average of 0.3 (2017 to 2019) at the same time of the year.

So far this season there have been 5 recorded deaths within 7 days of an iGAS diagnosis in children under 10 in England. During the last high season for Group A Strep infection (2017 to 2018) there were 4 deaths in children under 10 in the equivalent period.

Investigations are also underway following reports of an increase in lower respiratory tract Group A strep infections in children over the past few weeks, which have caused severe illness.

Currently, there is no evidence that a new strain is circulating. The increase is most likely related to high amounts of circulating bacteria and social mixing.

(Continue . . . )

Note: Overnight UK media are reporting a 6th pediatric fatality.

The UK's weekly surveillance report makes it clear this is more than just a return to pre-pandemic levels of Scarlet Fever/iGAS, as they find "The rate of iGAS at this point in the season is higher in all age groups compared with the pre-pandemic average".

Antimicrobial susceptibility results from routine laboratory surveillance so far this season indicate tetracycline resistance in 25% of GAS sterile site isolates; this is lower than at this point last season (45%). Susceptibility testing of iGAS isolates against erythromycin indicated 7% were found resistant (compared with 19% last season), and for clindamycin, 7% were resistant at this point in the season (16% last season). Isolates remained universally susceptible to penicillin.Analysis of reference laboratory iGAS isolate submissions indicate a diverse range of emm gene sequence types identified between October and November 2022. The results indicate the emm 1 are the most common (24% of referrals), followed by emm 12 (20%), emm 89 (8%), emm 108 and emm 33 (each 5%). In children (aged 15 years and under) emm 12 and emm 1 have dominated in 2022, accounting for 39% and 35% respectively. In contrast, during 2021, emm 89 was the most frequently identified (13%), followed by emm 108 (12%), then emm 66 (11%).

(SNIP)Discussion

There has been a steep increase in scarlet fever notification and GP consultations early in the 2022 to 2023 season which is steeper than would be expected at this time of the year. The rate of iGAS infection notifications is following a similar but less pronounced increase, with weekly incidence trending slightly above what would be expected at this point in the season.In children under 10 years, the rate of iGAS infection has been higher than levels reported in the years preceding the COVID-19 pandemic but substantially higher than the past 2 years. Investigations are underway following reports of an increase in lower respiratory tract GAS infections, particularly empyema, in children over the past few weeks.The elevated iGAS levels in children compared to the period when these pandemic control measures were in place is likely to be a consequence of the heightened scarlet fever activity given the crossover of strains associated in both presentations (1, 2).Prompt treatment of scarlet fever with antibiotics is recommended to reduce risk of possible complications and limit onward transmission. Public health messaging to encourage contact with NHS 111 and/or GP practices for clinical assessment of patients with specific symptoms (for example, rash) is underway. GPs and other frontline clinical staff are reminded of the increased risk of invasive disease among household contacts of scarlet fever cases (3, 4).Clinicians should continue to be mindful of potential increases in invasive disease and maintain a high index of suspicion in relevant patients and provide safety netting advice as appropriate, as early recognition and prompt initiation of specific and supportive therapy for patients with iGAS infection can be life-saving.

The resurgence of non-pandemic infectious diseases after a two-year hiatus is not unexpected, and has been well discussed here (see MJA: Preparing For Out-of-Season Influenza Epidemics When International Travel Resumes), and in other venues.

It would not be surprising if the patterns we've already seen with RSV, influenza, and scarlet fever are repeated with other infectious diseases. Measles is also on the ascendant around the world, polio is a re-emerging threat, and the world may be ripe for another adenovirus outbreak.

Add in the novel threats, like MERS-CoV, EA H1N1 `G4', avian H5Nx, or the yet to be discovered CLADE X, and you have ample reasons to prepare for an uncertain, and potentially perilous, future.

Which is why we need to be more concerned about how we'll deal with the next pandemic, than when we can call an end to this one.