#17,322

- Tuberculosis probably jumped to humans when we began to domesticate goats and cattle 5000 years ago.

- Measles appears to have evolved from canine distemper and/or the Rinderpest virus of cattle.

- And Influenza, which appears to have originated in aquatic birds, became much more of a threat after humans domesticated ducks, geese, and chickens.

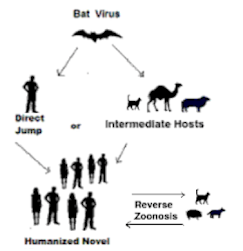

The odds are, the next major global health threat will emerge from a zoonotic source.

SARS-CoV-2 mink-associated variant strain – DenmarkDisease Outbreak News: Update3 December 2020

Since June 2020, Danish authorities have reported an extensive spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, on mink farms in Denmark. On 5 November, the Danish public health authorities reported the detection of a mink-associated SARS-CoV-2 variant with a combination of mutations not previously observed (referred to as “Cluster 5”) in 12 human cases in North Jutland, detected from August to September 2020.

While the Alpha variant quickly overran these `mink variants', it demonstrated the potential for a new COVID variant to evolve within a non-human host species.

Since then, we've seen numerous examples of companion animals (dogs, cats, hamsters, rats, etc.) becoming infected - including rare transmission back to humans - and spillovers into wildlife (see PNAS: White-Tailed Deer as a Wildlife Reservoir for Nearly Extinct SARS-CoV-2 Variants).

A little over a month ago, in Nature: Comparative Susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV Across Mammals, we looked at the wide variety of non-human hosts susceptible to coronavirus infections (see chart below).

The threat of new variants emerging from non-human hosts is genuine, which is why nearly a year ago WHO/FAO/OIE issued a Joint Statement On Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 In Wildlife & Preventing Formation of Reservoirs.

We've seen other reports - including CCDC Weekly Perspectives: COVID-19 Expands Its Territories from Humans to Animals from China - which have warned that the spillover of COVID into other species provides the virus with new opportunities to evolve, adapt, and potentially return with a vengeance.

While unproven, there is even some evidence to suggest the Omicron Variant may have evolved after the virus jumped to mice or other rodents (see Evidence for a mouse origin of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant), and then spilled back into humans (see also WOAH Statement).

But regardless of Omicron's origin, the SARS-CoV-2 genie is out of the bottle, and it has a multitude of evolutionary avenues to explore.

Yesterday the ECDC published a lengthy (108 page) review, scientific opinion, and risk assessment on the susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 in animals. Due to its size, I've only reproduced the summary below, so follow the link to download the full report.

SARS-CoV-2 in animals: susceptibility of animal species, risk for animal and public health, monitoring, prevention and control

Risk assessment

28 Feb 2023

The epidemiological situation of SARS-CoV-2 in humans and animals is continually evolving. To date, animal species known to transmit SARS-CoV-2 are American mink, raccoon dog, cat, ferret, hamster, house mouse, Egyptian fruit bat, deer mouse and white-tailed deer.

Among farmed animals, American mink have the highest likelihood to become infected from humans or animals and further transmit SARS-CoV-2.In the EU, 44 outbreaks were reported in 2021 in mink farms in seven MSs, while only six in 2022 in two MSs, thus representing a decreasing trend. The introduction of SARS-CoV-2 into mink farms is usually via infected humans; this can be controlled by systematically testing people entering farms and adequate biosecurity.

The current most appropriate monitoring approach for mink is the outbreak confirmation based on suspicion, testing dead or clinically sick animals in case of increased mortality or positive farm personnel and the genomic surveillance of virus variants.The genomic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 showed mink-specific clusters with a potential to spill back into the human population.Among companion animals, cats, ferrets and hamsters are those at highest risk of SARSCoV-2 infection, which most likely originates from an infected human, and which has no or very low impact on virus circulation in the human population.Among wild animals (including zoo animals), mostly carnivores, great apes and white-tailed deer have been reported to be naturally infected by SARS-CoV-2. In the EU, no cases of infected wildlife have been reported so far.Proper disposal of human waste is advised to reduce the risks of spill-over of SARS-CoV-2 to wildlife. Furthermore, contact with wildlife, especially if sick or dead, should be minimised. No specific monitoring for wildlife is recommended apart from testing hunter-harvested animals with clinical signs or found-dead. Bats should be monitored as a natural host of many coronaviruses.