Influenza's superpower is its ability reinvent itself via reassortment - and while most reassortants either add nothing of value or are evolutionary failures - the virus that emerged in 2020 had newfound abilities to spread globally via migratory birds and a tendency to spillover into mammals.

After two decades of being primarily an Asian and European threat, in late 2021 HPAI H5 arrived in Eastern Canada and Western Canada (via two different routes); crossing both the Pacific and the Atlantic, then spread rapidly across all of North America.

Somewhat ominously, many of these mammalian infections presented with profound neurological manifestations (see Cell: The Neuropathogenesis of HPAI H5Nx Viruses in Mammalian Species Including Humans).

While we've seen hundreds of reports of HPAI H5 infection in foxes, skunks, wild cats, and even bears - and tens of thousands of seals, sea lions, and otters - we are likely only seeing the tip of a much larger iceberg. Marine mammal victims - which tend to wash up on very public beaches - are far more easily noticed than terrestrial mammals who may perish unseen in remote woods, swamps, and deserts.

Surveillance is spotty at best - even in the United States and Europe - but it is likely nonexistent in many parts of the world.

Over the summer we saw two high profile outbreaks of HPAI H5N1 in cats (in South Korea and in Poland). Yesterday we looked at a proposed serpprevalence study of stray and domestic cats this winter in the Netherlands to look for signs of HPAI H5N1 infection.

Today, we've the results of another study - this time from Erasmus University - which finds a much higher than expected level of HPAI H5 infection and antibodies among wild carnivores in the Netherlands. They also represent evidence that spillover into mammals may have been more common than believed during the first (2016-2017) avian epizootic in Europe.

Due to its length I've only posted some excerpts, so follow the link to read it in its entirety. I'll have a postscript after the break.

Article: 2270068 | Received 14 May 2023, Accepted 05 Oct 2023, Published online: 01 Nov 2023

ABSTRACT

In October 2020, a new lineage of a clade 2.3.4.4b HPAI virus of the H5 subtype emerged in Europe, resulting in the largest global outbreak of HPAI to date, with unprecedented mortality in wild birds and poultry. The virus appears to have become enzootic in birds, continuously yielding novel HPAI virus variants. The recently increased abundance of infected birds worldwide increases the probability of bird–mammal contact, particularly in wild carnivores.

Here, we performed molecular and serological screening of over 500 dead wild carnivores and sequencing of RNA positive materials. We show virological evidence for HPAI H5 virus infection in 0.8%, 1.4%, and 9.9% of animals tested in 2020, 2021, and 2022 respectively, with the highest proportion of positives in foxes, polecats and stone martens.

We obtained near full genomes of 7 viruses and detected PB2 amino acid substitutions known to play a role in mammalian adaptation in three sequences. Infections were also found in without neurological signs or mortality. Serological evidence for infection was detected in 20% of the study population.

These findings suggests that a high proportion of wild carnivores is infected but undetected in current surveillance programmes. We recommend increased surveillance in susceptible mammals, irrespective of neurological signs or encephalitis.

(SNIP)

Discussion

This study shows that the exposure and number of HPAI H5 virus infections between 2020 and 2022 in wild carnivores was much higher than previous reports suggested. Our serology studies demonstrated that significant proportions of foxes and stone martens that were found dead had antibodies against HPAI H5 virus. The same animal species also tested positive for HPAI H5, with 29% of dead foxes and 24% of dead polecats testing RNA positive. Data from 2016 and 2017 shows that wild carnivore neurological complications.

Therefore, carnivores that do not show abnormal neurological behaviour or encephalitis may also be infected frequently, and serology indicated that exposure does not always lead to mortality. Data from 2016 and 2017 indicated that wild carnivore infections were also occurring during previous outbreaks of clade 2.3.4.4b HPAI H5 viruses.

The current HPAI H5 virus outbreak is the largest outbreak ever reported, and since 2021, HPAI H5 viruses can be detected year-round in Europe. Between 2020 and 2022 over 5 million chickens and ducks have been culled in the Netherlands (LINK), retrieved on 15 August 2023), and tens of thousands of wild birds died due to HPAI H5 infections in the same period. Since most wild carnivore infections are likely caused by predation or direct contact with sick or dead wild birds [Citation4,Citation5], both the magnitude and timing of infections in birds will affect the number of carnivore infections that occur.

Our study indeed suggests an increase in wild carnivore infections in 2022, versus 2020 and 2021, based on molecular screening and serology. However, the nature of the survey precludes robust conclusions. The results of the serological analysis of sera from 2016 and 2017 suggest that exposure rates may also have been high during previous clade 2.3.4.4b HPAI H5 virus outbreaks. The drop in seroprevalence between 2017 and 2020 is likely explained by antibody waning and lack of exposure of young animals in the absence of HPAI H5 virus outbreaks in the Netherlands between 2018 and 2020.

(SNIP)Conclusion

Here, we show that foxes, polecats and stone martens are infected frequently with clade 2.3.4.4b HPAI H5 viruses, with and without clear neurological signs or mortality. Some of the viruses showed evidence for adaptation to mammals. This demonstrates the need for increased surveillance of all wild carnivores to monitor infections and mutations, irrespective of neurological signs.

Increased surveillance should also include other wild and domesticated animal species, such as swine, mink, cats, dogs, and more. Also, avian influenza infections in rodents have been described, but so far rarely any monitoring or field research is targeting them. Especially species that are susceptible to human as well as avian influenza viruses are of relevance, because of the risk of reassortment. Initiating such active monitoring of both live and deceased animals will not only contribute to our understanding of the epidemiology and pathogenesis of currently circulating HPAI virus strains, but will also aid in the timely identification of novel high-risk variants.

HPAI H5N1 clade 2.3.4.4b may sound fairly specific, but it encompasses a great many closely related viruses. Invariably, some will prove more pathogenic - and have different host ranges - than others.

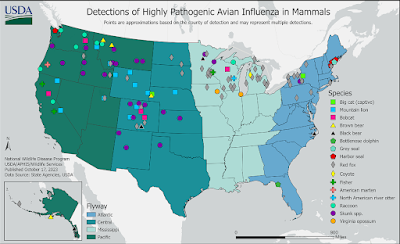

Today's study reminds us, that when we see maps like the following from the USDA showing mammalian infection with HPAI H5 in the United States, it only represents a tiny fraction of what is happening in the wild.

Farmed mammals may also contribute to the spread and evolution of HPAI H5N1. A year ago, a worrisome variant of H5N1 emerged from a mink farm in Spain, leading to the CDC to add it to their IRAT list (see CDC: New IRAT Risk Assessment On Mink Variant of Avian H5N1).

More recently, dozens of Finnish fur farms have reported HPAI H5 spreading through mink, foxes, and raccoons, which has resulted in the culling of hundreds of thousands of infected or exposed animals.Last May, in Netherlands: Zoonoses Experts Council (DB-Z) Risk Assessment & Warning of Swine As `Mixing Vessels' For Avian Flu, we looked at concerns that avian H5N1 could increase its pandemic threat by spreading (and evolving) in farmed swine.

That announcement was followed a week later by a report (see Study: Seroconversion of a Swine Herd in a Free-Range Rural Multi-Species Farm against HPAI H5N1 2.3.4.4b Clade Virus) at a `mixed species' farm (poultry & swine) in Italy.

COVID proved to the world that severe pandemics are not just a relic of the past, but a genuine threat in this 21st century. Studies suggest they may increase in frequency 3-fold over the next 20 years, and as bad as COVID was, it may not be the worst that nature can (or will) throw at us.

Even if H5N1 fizzles as a pandemic, somewhere out there is a novel virus with humanity's name on it. If we don't actively look for it now, we may never see it coming.