Note: Those familiar with OAS (original antigenic sin) and immune imprinting may wish to skim, or skip, my rather lengthy intro.

#18,390

Nearly 18 years ago, in a blog called A Predilection For The Young, I wrote about H5N1's affinity for infecting, and often killing, younger adults, adolescents, and children. The WHO chart (above) illustrates that pattern with disturbing clarity.

Six years later we saw the opposite trend with avian H7N9 in China, which skewed heavily toward older adults (see H7N9: The Riddle Of The Ages).

The concern here is that an H5N1 pandemic might be far more impactful for young adults and children than for those, say . . . over 50. While we think of flu taking its biggest toll on the elderly, we've seen 3 flu pandemics in relatively recent history where the burden shifted to a younger cohort.

- The 1918 pandemic showed a unique W-Shaped Curve (see below), where young adults (25-30) were particularly hard hit, while mortality rate actually dropped in those over the age of 60.

- In 1978, H1N1 returned after an absence of 20 years (potentially from a lab leak in Russia or China) sparking a pseudo-pandemic (aka `the Russian Flu') that primarily affected those under the age of 20 (see mBio: The Reemergence Of H1N1 in 1977 and The GOF Debate).

- While the average (mean) age of a flu-related fatality in a `normal’ flu season here in the United States is about 76 years, the average during the (relatively mild) 2009 H1N1 pandemic was half that; at 37.4 years (see Study: Years Of Life Lost Due To 2009 Pandemic).

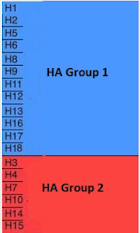

- Those born prior to the mid-1960s were almost certainly first exposed to Group 1 flu viruses (H1N1 or H2N2)

- Those born after 1968 and before 1977 would have been exposed to Group 2 (H3N2)

- After 1977, both Group 1 and 2 viruses co-circulated, meaning the first exposure could have been to either one.

Over the past few months we've looked a a flurry of studies on the immune response to H5N1 (an HA Group 1 virus), and the effects of previous H1N1 vaccination and/or infection. A few of many include:

Two More Preprints Suggesting Prior H1N1 Infection May Provide Some Cross-Protection Against `Bovine' HPAI H5N1

Preprint: Targets of influenza Human T cell Response are Mostly Conserved in H5N1

Preprint: Pre-existing H1N1 Immunity Reduces Severe Disease with Cattle H5N1 Influenza Virus

Frontiers Vet. Sci: Influenza Virus Immune Imprinting - Clinical Outcome In Ferrets Challenged with HPAI H5N1

All of which brings us to a new preprint, which suggests that younger people may be more heavily impacted by an H5 virus, and that they may benefit more from a pandemic vaccine than adults. I've only posted the abstract, and some brief excerpts, so follow the link to read it in its entirety.

I'll have a bit more after the break.

Immune history shapes human antibody responses to H5N1 influenza viruses

Tyler A. Garretson, Jiaojiao Liu, Shuk Hang Li, Gabrielle Scher, Jefferson J.S. Santos, Glenn Hogan, Marcos Costa Vieira, Colleen Furey, Reilly K. Atkinson, Naiqing Ye, Jordan Ort, Kangchon Kim, Kevin A. Hernandez, Theresa Eilola, David C. Schultz, Sara Cherry,arah Cobey, Scott E. Hensley

doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.10.31.24316514

Preview PDF

Abstract

Avian H5N1 influenza viruses are circulating widely in cattle and other mammals and pose a risk for a human pandemic. Previous studies suggest that older humans are more resistant to H5N1 infections due to childhood imprinting with other group 1 viruses (H1N1 and H2N2); however, the immunological basis for this is incompletely understood.Here we show that antibody titers to historical and recent H5N1 strains are highest in older individuals and correlate more strongly with year of birth than with age, consistent with immune imprinting.After vaccination with an A/Vietnam/1203/2004 H5N1 vaccine, both younger and older humans produced H5-reactive antibodies to the vaccine strain and to a clade 2.3.4.4b isolate currently circulating in cattle, with higher seroconversion rates in young children who had lower levels of antibodies before vaccination. These studies suggest that younger individuals might benefit more from vaccination than older individuals in the event of an H5N1 pandemic.

Based on our studies and the observation that H5N1 viruses have typically caused more disease in younger individuals 15,16, it is possible that older individuals would be partially protected in the event of an H5N1 pandemic.Younger individuals who have fewer group 1 influenza virus exposures would likely benefit more from an H5N1 vaccine, even a mismatch stockpiled vaccine 28 174 . It will be important to continue to test new updated vaccine antigens in individuals with diverse birth years, including children.It will also be important to closely monitor clade 2.3.4.4b H5N1 virus circulating in wild and domestic animals, as well as spillover infections of humans, so that we can continue to evaluate the pandemic risk of these viruses.

Although recent reports of `mild' H5N1 infections in American farm workers are somewhat reassuring, there are no guarantees how long that will persist.

The virus continues to evolve, and in Cambodia H5N1 has killed roughly 1/3rd of those that it has hospitalized over the past 2 years, and in China, H5N6 has a reported fatality rate of 50%.

While it is widely assumed that some (perhaps large) number of milder cases go unreported, and the `real world' CFR (Case Fatality Rate) is likely far lower, even a 1%-2% fatality rate would have a devastating impact.

Any `protection' provided by past exposure to HA Group 1 viruses is likely to be limited, and any advantage to those born before 1968 may be offset by other age-related comorbidities. Which makes the rapid development of a safe and effective H5 vaccine a high priority.

But, as we saw last week in SCI AM - A Bird Flu Vaccine Might Come Too Late to Save Us from H5N1 - there are many obstacles to overcome - including the growing public distrust of vaccines.

Given the stakes, it is still worth doing everything we can to keep the H5N1 virus from becoming a pandemic.