#18,350

There are now well over 100 cats confirmed with H5N1 in the United States over the past 12 months, and while most of them have been reported in western states, the recent eastward surge of H5N1 across the nation via migratory birds has put more animals at risk.

Today we've this report from the New Jersey Department of Health.

While the headline from the press release, and the opening paragraph, make this sound like only one cat was found infected, as we read further down we learn that other cats on the property are ill - a second (indoor) cat has tested positive - and additional tests are pending.

H5 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza Confirmed in New Jersey Cat

Caution Advised Though H5N1 Public Health Risk to Humans Remains Low

TRENTON, NJ - The first feline case of H5 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI or “bird flu”) in New Jersey has been confirmed in a feral cat from Hunterdon County. The case was confirmed by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) National Veterinary Services Laboratory, and follows previous national reports of confirmed feline cases in other states.

The cat developed severe disease, including neurologic signs, and was humanely euthanized. Other cats on the same property were also reported ill, and one additional indoor-outdoor cat was subsequently confirmed positive for H5 HPAI. Other tests are still pending, and the investigation is ongoing.

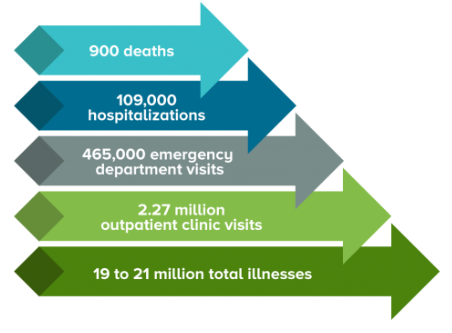

The overall public health risk remains low at this time. While H5 HPAI has been detected in humans in the U.S. – primarily in individuals with close contact with infected poultry or dairy cattle – there have been no human cases reported in New Jersey, and none of the cases across the country are known to have resulted from exposure to an infected cat.

Local health officials are working closely with the New Jersey Department of Health in conducting follow up and symptom monitoring on individuals that have been in contact with these cats. All exposed individuals are currently asymptomatic. Residents who have had close, unprotected contact with a cat or other animal infected with H5 HPAI should contact their local health department and monitor themselves for symptoms for 10 days following their last exposure.

“While the risk of H5 infection to the general population remains low at this time, it is important for people to learn more about the situation and take steps to avoid potential infection through exposure to animals, including feral cats,” said New Jersey Health Commissioner Kaitlan Baston, MD, MSc, DFASAM. “We continue to work with state and federal partners to monitor the spread of this virus and provide public information on mitigating the risks.”

Cats are particularly susceptible to H5 HPAI and often experience severe disease and high mortality when infected. Potential exposure sources of H5 HPAI for cats include consuming raw (unpasteurized) milk or raw/undercooked meat contaminated with the virus, infected birds or other animals and their environments, or exposure to contaminated clothing or items (fomites) worn or used on affected premises.

The cats tied to this incident in Hunterdon County had no known reported exposures to infected poultry, livestock, or consumption of raw (unpasteurized) milk or meat, but did roam freely outdoors, so exposure to wild birds or other animals is unknown.

Clinical signs in cats can include:

- General signs: Loss of appetite, fever, lethargy

- Respiratory signs: Discharge from the eyes and mouth, sneezing, coughing, difficulty breathing

- Neurologic signs: Seizures, circling, wobbling gait, blindness.

New Jersey residents should contact their veterinarian immediately if they are concerned that their cat may have H5 bird flu. Anyone who suspects a possible exposure or who has H5 HPAI concerns about their cat should contact their veterinarian prior to bringing the cat in to be seen so that the veterinarian can take the necessary precautions to prevent spread of disease. Residents who observe a sick stray or feral cat should contact their local animal control for assistance.

Veterinarians who suspect H5 HPAI in a cat should follow CDC recommendations to help protect themselves and prevent exposures, including wearing personal protective equipment (PPE) when handling the cats. All suspect feline cases should be reported to the New Jersey Department of Health Communicable Disease Service at 609-826-4872 or zoonoticrn@doh.nj.gov. Testing for suspect feline cases is available at the New Jersey Animal Health Diagnostic Laboratory, a member of the USDA’s National Animal Health Laboratory Network. Guidance for veterinarians on specimen collection and submission can be found here.

New Jersey residents can find additional information and recommendations on ways to help prevent H5 bird flu infection in cats from the American Veterinary Medical Association.

Additionally, cat owners can take the following steps to help protect their pets:

- Do not feed cats raw (unpasteurized) milk or dairy products, and avoid feeding any raw or undercooked meat treats or diets.

- Keep cats indoors to prevent exposure to birds and other wildlife.

- Keep cats away from livestock, poultry, and their environments.

- Avoid contact with sick or dead birds and other wildlife yourself.

- Thoroughly wash your hands after handling your cat and after any encounters with poultry, livestock, or wild birds and other animals.

- Change your clothes and shoes, and thoroughly wash any exposed skin, after interacting with sick or dead animals that may harbor the H5N1 virus, and before interacting with your cat.

- Contact a veterinarian if you notice signs of H5 HPAI or think your cat might have been exposed to the virus.

“The H5N1 virus has the ability to move from one species to another,” New Jersey Agriculture Secretary Ed Wengryn said. "That is why we have worked closely with our poultry and dairy industries on biosecurity measures to prevent exposure by wild animals, and feral cats are another example of the risks to livestock and humans.”

“Despite low risk to the public, avian influenza is believed to be present in wild birds in all of New Jersey’s counties,” Environmental Protection Commissioner Shawn M. LaTourette said. “The Department of Environmental Protection continues to work closely with state and federal partners to track and respond to avian flu in wild birds and keep the public informed.”

NJDOH continues to work in collaboration with the NJ Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) and the NJ Department of Agriculture (NJDA) to monitor occurrences of H5N1 Avian Influenza and its impact in the State.

- If you find sick or dead wild birds, do not handle them. Contact the NJDEP’s Fish and Wildlife hotline at 1-877-WARNDEP.

- To report sick or dead poultry, do not handle them. Contact the NJDA Division of Animal Health at 609-671-6400.