# 9051

The 54rd Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC) runs through September 9th in Washington D.C. , and this morning we’ve an absolutely fascinating video sponsored by the American Society for Microbiology showing just how quickly a single introduction of a virus into an office environment can spread to contaminate an entire building.

Of particular interest, this conversation explores how their results relate to this week’s Enterovirus (HEV-D68) outbreak (see Enterovirus D-68 (HEV-D68) Update).

First, the press release on the study, then a link to the video on MicrobeWorld’s Youtube channel.

How Quickly Viruses Can Contaminate Buildings and How to Stop Them

EMBARGOED UNTIL: Monday, September 8, 2014, 9:00 a.m. EDT

(Images are courtesy Gerba Lab and are free to use. First image is Gerba and a student working on samples and second is a sampling sponge.)

WASHINGTON, DC – September 8, 2014 – Using tracer viruses, researchers found that contamination of just a single doorknob or table top results in the spread of viruses throughout office buildings, hotels, and health care facilities. Within 2 to 4 hours, the virus could be detected on 40 to 60 percent of workers and visitors in the facilities and commonly touched objects, according to research presented at the 54th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy (ICAAC), an infectious disease meeting of the American Society for Microbiology.

There is a simple solution, though, says Charles Gerba of the University of Arizona, Tucson, who presented the study.

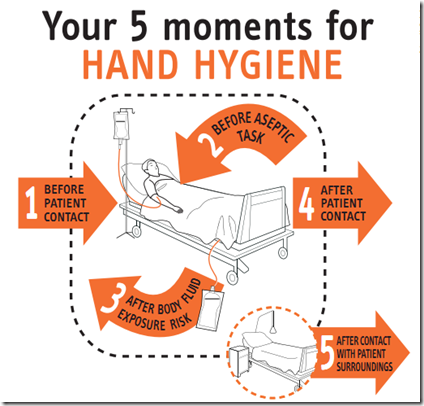

“Using disinfecting wipes containing quaternary ammonium compounds (QUATS) registered by EPA as effective against viruses like norovirus and flu, along with hand hygiene, reduced virus spread by 80 to 99 percent,” he says.

The video is available on the http://www.microbeworld.org/podcasts/asm-live website right now, but should be moved to the MicrobeWorld’s Youtube channel later today.

Monday, September 8

9:00 a.m. -- How Quickly Viruses Can Contaminate a Building

Using tracer viruses, researchers found that contamination of just a single doorknob or table top results in the spread of viruses throughout office buildings, hotels, and health care facilities. Within 2 to 4 hours, the virus could be detected on 40 to 60 percent of workers and visitors in the facilities and commonly touched objects. Simple use of common disinfectant wipes reduced virus spread by 80 to 99 percent.Charles Gerba, University of Arizona, Tucson

Sigh. Based on this, and the viral threats lining up, guess I’m gonna need to lay in a bigger supply of hand sanitizer.