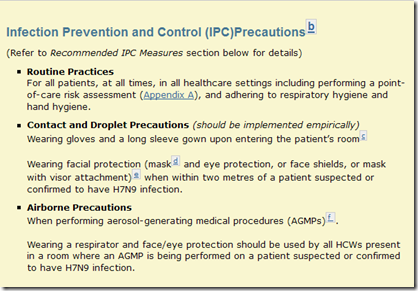

Female blacklegged ticks in various

stages of feeding. Note the change in

size and colour.- Credit PHAC

#7527

Lyme disease, spread by infected ticks, has become a major vector-borne disease in the United States with nearly 35,000 confirmed or suspected cases reported in 2011 (cite Reported Cases of Lyme Disease by Year, United States, 2002-2011).

While cases have been reported in Canada (Lyme became a reportable disease there in 2009), they have run about 1/100th the rate seen in the United States (just 258 cases in 2011).

But those numbers may poised to increase, according to the following public health notice posted today by the PHAC, as infected ticks appear to be spreading into new regions of Canada.

Why you should take note

Lyme disease is a serious illness spread by the bite of certain ticks; specifically, blacklegged ticks. Ticks are small, insect-like parasites that feed on the blood of animals, including humans. In regions where blacklegged ticks are found, people can come into contact with ticks by brushing against vegetation while participating in outdoor activities, such as, hiking, camping and gardening. When a tick bites, it attaches to the skin and the bite is usually painless. For most Canadians, the risk of getting Lyme disease is fairly low, but is increasing.

Risk to Canadians

The Public Health Agency of Canada, in partnership with provincial and territorial public health authorities, conducts surveillance for Lyme disease in Canada and studies show the risk of the disease is growing in this country. Risk occurs in parts of Manitoba, Ontario, southern Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and southern British Columbia, and is increasing in south eastern and south central Canada due to spread of populations of the ticks that carry the bacterium that causes Lyme disease.

You are most at risk of being exposed to Lyme disease in the regions listed above where blacklegged and western blacklegged ticks are found. But migratory birds can also carry these ticks to other parts of Canada. Current research tells us that blacklegged ticks may be establishing themselves in new areas that are not identified yet. This may mean that risk of Lyme disease may occur over broader regions of Canada than we are presently aware of.

Although blacklegged ticks can be active throughout much of the year in some locations, your risk of acquiring Lyme disease, especially in areas where tick populations are established, is greatest during the summer months when younger ticks are most active.

Lyme disease is much more common in the United States than in Canada, with risk areas in the Midwest and northeastern states. In 2011, approximately 35,000 cases of Lyme disease were reported in the United States compared to approximately 258 cases in Canada for the same year.

(Continue . . . )

As Public Health Canada’s Lyme FAQ explains, black legged ticks carry and can transmit more than just Lyme disease:

Although rarer than Lyme disease, there are other infections that can also be contracted from blacklegged ticks. These include Anaplasma phagocytophilum, the agent of human granulocytic anaplasmosis; Babesia microti, the agent of human babesiosis and Powassan encephalitis virus. Most of the precautions outlined above will also help to protect individuals from these infections.

The CDC lists a growing number of diseases carried by ticks in the United States, including: Anaplasmosis, Babesiosis , Ehrlichiosis, Lyme disease, Rickettsia parkeri Rickettsiosis, Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF), STARI (Southern Tick-Associated Rash Illness), Tickborne relapsing fever (TBRF), Tularemia, and 364D Rickettsiosis.

We’ve discussed a number these in the past, including:

Referral: Maryn McKenna On Babesia And The Blood Supply

NEJM: Emergence Of A New Bacterial Cause Of Ehrlichiosis

New Phlebovirus Discovered In Missouri

tick . . . tick . . . tick . . .

Minnesota: Powassan Virus Fatality

When you consider the wide panoply of diseases carried by ticks it makes sense to avoid tick bites whenever possible.

This from the Minnesota Department of Health.

Lastly, the CDC offers the following advice:

Preventing Tick Bites

While it is a good idea to take preventive measures against ticks year-round, be extra vigilant in warmer months (April-September) when ticks are most active.

Avoid Direct Contact with Ticks

- Avoid wooded and bushy areas with high grass and leaf litter.

- Walk in the center of trails.

Repel Ticks with DEET or Permethrin

- Use repellents that contain 20% or more DEET (N, N-diethyl-m-toluamide) on the exposed skin for protection that lasts up to several hours. Always follow product instructions. Parents should apply this product to their children, avoiding hands, eyes, and mouth.

- Use products that contain permethrin on clothing. Treat clothing and gear, such as boots, pants, socks and tents. It remains protective through several washings. Pre-treated clothing is available and remains protective for up to 70 washings.

- Other repellents registered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) may be found at http://cfpub.epa.gov/oppref/insect/.

Find and Remove Ticks from Your Body

- Bathe or shower as soon as possible after coming indoors (preferably within two hours) to wash off and more easily find ticks that are crawling on you.

- Conduct a full-body tick check using a hand-held or full-length mirror to view all parts of your body upon return from tick-infested areas. Parents should check their children for ticks under the arms, in and around the ears, inside the belly button, behind the knees, between the legs, around the waist, and especially in their hair.

- Examine gear and pets. Ticks can ride into the home on clothing and pets, then attach to a person later, so carefully examine pets, coats, and day packs. Tumble clothes in a dryer on high heat for an hour to kill remaining ticks.