*** Correction *** H1N1v was inadvertently listed as H3N2v in original post – Mea culpa.

# 9650

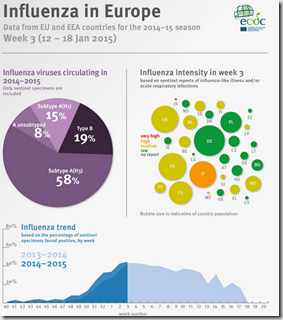

Since we’ve got a drifted `H3N2’ virus running rampant across much of the northern hemisphere, an unusually vigorous outbreak of H5N1 in Egypt, our regular winter H7N9 mini-epidemic in China, avian HPAI H5 viruses spreading impressively internationally, and even a pair of imported H7N9 cases in Canada this week . . .it makes perfect sense that the latest MMWR & FluView would include news of an uncharacteristically out-of-season H1N1v infection in Minnesota as well.

H1N1v is a swine H1N1 virus - that when it jumps to humans - gets the `variant’ tag.

Although telegraphed in yesterday’s MMWR, the following announcement appears in today’s FluView Report.

Novel Influenza A Virus:

One human infection with a novel influenza A virus was reported by the state of Minnesota. The person was infected with an influenza A (H1N1) variant (H1N1v) virus, and has fully recovered from their illness. No ongoing human-to-human transmission has been identified and the case patient reported contact with swine in the week prior to illness onset.

Early identification and investigation of human infections with novel influenza A viruses are critical in order to evaluate the extent of the outbreak and possible human-to-human transmission. Additional information on influenza in swine, variant influenza infection in humans, and strategies to interact safely with swine can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/flu/swineflu/index.htm.

Over the past few years we’ve watched as several swine variant influenza viruses (H1N1v, H1N2v or H3N2v) have made tentative jumps into the human population (see Keeping Our Eyes On The Prize Pig) and each summer the CDC has issued advice on preventing infection at county and state fairs (see Measures to Minimize Influenza Transmission at Swine Exhibitions, 2014).

We’ve not seen many reported cases the past couple of years, but during the summer of 2012 more than 300 cases were detected, with Indiana and Ohio accounting for roughly 80% of the cases.

Illnesses were usually mild or moderate (1 fatality was recorded), and infection usually occurred in the summer and fall and was associated with attendance of local and state fairs where pigs were being shown. Of course, some people have contact with swine all year round, and so while uncommon, it isn’t terribly surprising that someone would contract H3N2v during the winter.

What is surprising is that it - like we saw with H7N9 in Canada earlier this week – this novel virus was detected against the background noise of a particularly nasty H3N2 influenza season.

While occasional cases are not particularly alarming, we keep an eye on these swine variant viruses because research has shown there to be only limited community immunity against them (see CIDRAP: Children & Middle-Aged Most Susceptible To H3N2v).

Of more immediate concern is this year’s seasonal flu activity, which remains brisk across much of the country, although in some states are seeing a drop in cases.

Hospitalization rates for the elderly (65+) are the highest ever recorded since the CDC began tracking that data in 2005, and the CDC continues to remind providers of value of early administration of antiviral medications (see Antiviral Letter to Providers).

This from today’s FluView Report.

All data are preliminary and may change as more reports are received.

Synopsis:

During week 3 (January 18-24, 2015), influenza activity remained elevated in the United States.

- Viral Surveillance: Of 23,339 specimens tested and reported by U.S. World Health Organization (WHO) and National Respiratory and Enteric Virus Surveillance System (NREVSS) collaborating laboratories during week 3, 4,651 (19.9%) were positive for influenza.

- Novel Influenza A Virus: One human infection with a novel influenza A virus was reported.

- Pneumonia and Influenza Mortality: The proportion of deaths attributed to pneumonia and influenza (P&I) was above the epidemic threshold.

- Influenza-associated Pediatric Deaths: Five influenza-associated pediatric deaths were reported.

- Influenza-associated Hospitalizations: A cumulative rate for the season of 40.5 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations per 100,000 population was reported.

- Outpatient Illness Surveillance: The proportion of outpatient visits for influenza-like illness (ILI) was 4.4%, above the national baseline of 2.0%. All 10 regions reported ILI at or above region-specific baseline levels. Puerto Rico and 29 states experienced high ILI activity; New York City and seven states experienced moderate ILI activity; six states experienced low ILI activity; eight states experienced minimal ILI activity; and the District of Columbia had insufficient data.

- Geographic Spread of Influenza: The geographic spread of influenza in Puerto Rico and 44 states was reported as widespread; the U.S. Virgin Islands and five states reported regional activity; and the District of Columbia, Guam, and one state reported local activity.

During week 3, 9.1% of all deaths reported through the 122 Cities Mortality Reporting System were due to P&I. This percentage was above the epidemic threshold of 7.1% for week 3.

Five influenza-associated pediatric deaths were reported to CDC during week 3. Four deaths were associated with an influenza A (H3) virus and occurred during weeks 53, 1, 2, and 3 (weeks ending January 3, January 10, January 17, and January 24, 2015, respectively). One death was associated with an influenza A virus for which no subtyping was performed and occurred during week 1.

A total of 61 influenza-associated deaths have been reported during the 2014-2015 season from New York City [1] and 24 states (Arizona [1], Colorado [2], Florida [2], Georgia [1], Indiana [1], Iowa [3], Kansas [2], Kentucky [3], Louisiana [2], Michigan [1], Minnesota [4], Missouri [1], North Carolina [2], Nevada [3], New York [1], Ohio [5], Oklahoma [4], Pennsylvania [1], South Carolina [1], South Dakota [1], Tennessee [4], Texas [7], Virginia [3], and Wisconsin [5]).

Additional data can be found at: http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/PedFluDeath.html.

View Interactive Application | View Full Screen | View PowerPoint Presentation

Between October 1, 2014 and January 24, 2015, 11,077 laboratory-confirmed influenza-associated hospitalizations were reported. The overall hospitalization rate was 40.5 per 100,000 population. The highest rate of hospitalization was among adults aged ≥65 years (198.4 per 100,000 population), followed by children aged 0-4 years (38.2 per 100,000 population). Among all hospitalizations, 10,690 (96.6%) were associated with influenza A, 290 (2.6%) with influenza B, 29 (0.3%) with influenza A and B co-infection, and 62 (0.5%) had no virus type information. Among those with influenza A subtype information, 3,016 (99.7%) were A(H3N2) virus and nine (0.3%) were A(H1N1)pdm09.

Clinical findings are preliminary and based on 1,729 (15.6%) cases with complete medical chart abstraction. The majority (93.7%) of hospitalized adults had at least one reported underlying medical condition; the most commonly reported were cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, and obesity. There were 230 hospitalized children with complete medical chart abstraction, 94 (40.9%) had no identified underlying medical conditions. The most commonly reported underlying medical conditions among pediatric patients were asthma, obesity, neurologic disorders and immune suppression. Among the 173 hospitalized women of childbearing age (15-44 years), 47 were pregnant.

Additional FluSurv-NET data can be found at: http://gis.cdc.gov/GRASP/Fluview/FluHospRates.html and http://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/fluview/FluHospChars.html

(Continue . . .)

Despite its reduced effectiveness, the CDC continues to recommend that people get the flu shot – partially because it may provide some modicum of protection against this drifted flu strain, and partly because we often see a wave of Influenza B late in the flu season, and the shot can help protect against that virus.

Beyond that, practicing good flu hygiene remains your best strategy for staying well; Staying home when sick, washing your hands, covering your coughs, and disposing of your tissues properly .