My Original Wuhan Post 12/31/19

#16,470

Two years ago tonight the dedicated newshounds at FluTrackers began posting numerous reports out of China on an outbreak of an unidentified viral pneumonia in Wuhan; the capital and largest city (pop. 11 million) in Hubei Province.

FluTrackers - which has volunteers monitoring international news feeds practically 24/7 - first post on the matter went live at 11:35 pm on the night of the 30th (see below).

By the time I had the story, and enough coffee to allow myself to write semi-coherently, FT had already published 7 reports. Before that first day had ended, they had posted more than a dozen more.

My first post went live at 3:54 am and would be the 1st of three I would publish that day (see here, here, and here).

While none of us knew the world was about to change, it `felt' important. Reminiscent, in some ways, of the early reports of H7N9 emerging in China on March 31st, 2013 (see China: Two Deaths From H7N9 Avian Flu).

Within hours Crof (who is 3 hours behind on the west coast) had his first blog (Hong Kong: CHP closely monitors cluster of pneumonia cases on Mainland), but it would literally be days before the mainstream news took notice.On January 6th, the CDC Issued a Level 1 (Watch) Travel Notice For Unidentified Pneumonia - Wuhan, China, but it would take another 10 days before the WHO would report `Evidence of Limited Human-to-Human Transmission' - WHO WPRO.

By that time, COVID was already well established in China, and rapidly wending its way across Europe and around the world.

While the world may have felt blindsided by COVID, this very scenario is one that had been discussed, analyzed, and had been the subject of numerous `tabletop' simulations over the years (see JHCHS Pandemic Table Top Exercise (EVENT 201) Videos Now Available Online).

Dire pre-COVID pandemic predictions by global health agencies include:

WHO/World Bank GPMB Pandemic Report : `A World At Risk'

WHO: On The Inevitability Of The Next Pandemic

World Bank: The World Ill-Prepared For A Pandemic

Six weeks before the Wuhan outbreak, in African Swine Fever's (ASF) Other Impacts; Pharmaceuticals, Bushmeat, and Food Insecurity, I even speculated that China's ASF outbreak could lead to increased `bushmeat' consumption, which in turn might spark another SARS-like outbreak.

A lucky guess, proving that if you write 15,000+ blog posts, you're bound to get something right eventually.

The point being, the only people who were truly surprised that the world was facing a pandemic threat in January of 2020 were those who hadn't been paying attention.

And sadly, despite the brutal lessons of the past two years, there are many plausible viral candidates for sparking the next pandemic that are given far less attention than they deserve.

While the list is long, three of the main contenders (and a bonus) include:

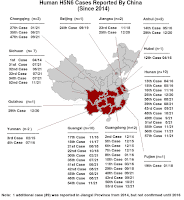

HPAI H5N6 Avian Influenza

China's H5N6 Problem - 31 Cases in 2021

It's been more than two weeks since the last report from China (see Hong Kong CHP Monitoring 4 More H5N6 Human Infections On the Mainland), but its a pretty safe bet that human infections with H5N6 haven't stopped now that winter has arrived.

China doles out infectious disease reports according to their own needs, and we often only hear about them weeks or months after the fact.

While H5N6 hasn't acquired the ability to transmit efficiently between humans, it continues to evolve, which has spurred a number of recent risk analyses from public health agencies around the globe (see here, here, and here), leading up to the CDC Adding A New H5N6 Avian Flu Virus To IRAT List three weeks ago.

Unlike COVID, which has a CFR (Case Fatality Rate) of 1%-2%, H5N1 has killed nearly half of those known to have been infected.

While H5N6 is currently our biggest HPAI H5 concern, it isn't the only one we are watching (see Science: Emerging H5N8 Avian Influenza Viruses).

In the 8 years prior to 2020, MERS had infected well over 2,000 people, and had sparked several large nosocomial outbreaks in hospitals in the Middle East and South Korea.

We have seen analyses (see Study: A Pandemic Risk Assessment Of MERS-CoV In Saudi Arabia), suggesting the virus doesn't have all that far to evolve before it could also pose a genuine global threat.

While nobody really knows how big of a threat it might pose, the possibility of SARS-CoV-2 and MERS-CoV simultaneously infecting the same host is regarded as a theoretical breeding ground - via recombination - of new, potentially more dangerous, coronaviruses (see Co-infection of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 in the same host: A silent threat).

Swine Variant Influenza (Including EA H1N1 `G4' )

The risk of one of these swine variant viruses sparking a pandemic is relatively low, but it isn't zero. A swine-origin H1N1v virus jumped to humans and sparked a mild-to-moderate flu pandemic in 2009, and the CDC currently ranks a Chinese Swine-variant EA H1N1 `G4' as having the highest pandemic potential of any flu virus on their list.

The CDC's IRAT (Influenza Risk Assessment Tool) also lists 3 North American swine viruses as having at least some pandemic potential (2 added in 2019).

H1N2 variant [A/California/62/2018] Jul 2019 5.8 5.7 Moderate

H3N2 variant [A/Ohio/13/2017] Jul 2019 6.6 5.8 Moderate

H3N2 variant [A/Indiana/08/2011] Dec 2012 6.0 4.5 Moderate

Bonus : Virus X

While this short list could easily include Monkeypox, Lassa Fever, and even Nipah the possibility exists that we could be hit by something entirely new, or at least not on our radar.A little over 4 months ago, in PNAS Research: Intensity and Frequency of Extreme Novel Epidemics, we looked at a paper that suggested that the probability of novel disease outbreaks will likely grow three-fold in the next few decades.

Like it or not, COVID-19 won't be the last - and perhaps not the worst - pandemic we'll face in the years ahead. The time to begin preparing is now, not after the next threat emerges.